In science, peer review plays a critical role in figuring out if research is good enough, robust enough. In this week’s episode, both of our storytellers find themselves looking for outside feedback on if they’re good enough.

Part 1: At her NASA summer internship, Kirsten Siebach feels completely out of place among the Mars mission scientists.

Kirsten Siebach is an Assistant Professor in the Rice University Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences and calls herself a Martian Geologist. She is currently a member of the Science and Operations Teams for the Mars 2020 rover Perseverance and the Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity, and previously worked on the science and engineering teams for the Phoenix Lander and the two Mars Exploration Rovers. She uses the images, chemistry, and other data that the rovers send back from Mars to study ancient environments on the Red Planet and compare them to ancient and modern environments on Earth. She received her bachelor’s degree in Earth and Planetary Science and Chemistry from Washington University in St. Louis and her Ph.D. in Geology from Caltech. Kirsten is actively engaged in science education and outreach and loves sharing the stories and images from Mars with students and the public. She has been interviewed in multiple documentaries and TV shows related to Mars exploration and has given over one hundred talks to students and interest groups around the world. Outside of professional interests, she loves travel and photography (on Earth as well as Mars), and enjoys swimming, hiking, and puzzles.

Part 2: Alison Spodek’s need to be seen as smart takes over her life.

Alison Spodek is a flamingo, majestically awkward in some circumstances, moderately graceful in others. A fierce competitor in her extended family’s daily Wordle competition, she is also an associate professor and chair of the chemistry department at Vassar College. There, her research focuses on the behaviors of all the most fun elements in the environment, particularly arsenic, mercury, lead, and uranium, but her real passion is helping people understand the world around them, particularly those who think they are “not good at science.” Alison got her master's degree in physical chemistry at Yale University and a PhD in Environmental Geochemistry at Columbia University. She lives in Beacon, NY with her husband, two kids, and a crotchety old dog.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

I was approaching the end of my freshman year of college at Washington University in St. Louis. I had gone to school planning to study chemistry, but in that first year had discovered Earth and Planetary Science. And so I thought, “Well, I better figure it all out this summer. I better find an internship that helps me figure out which of these fields I want to study and gives me experience so that I know what to do next.”

So I looked at all the internship programs I could. I was applying to these lists. I had pro/con lists. I had a very organized approach, I thought. I'm figuring out what I wanted to do. There was this one in Alaska and it was looking at chemistry and fish hatcheries or something. I was thinking of that because it sounded adventurous.

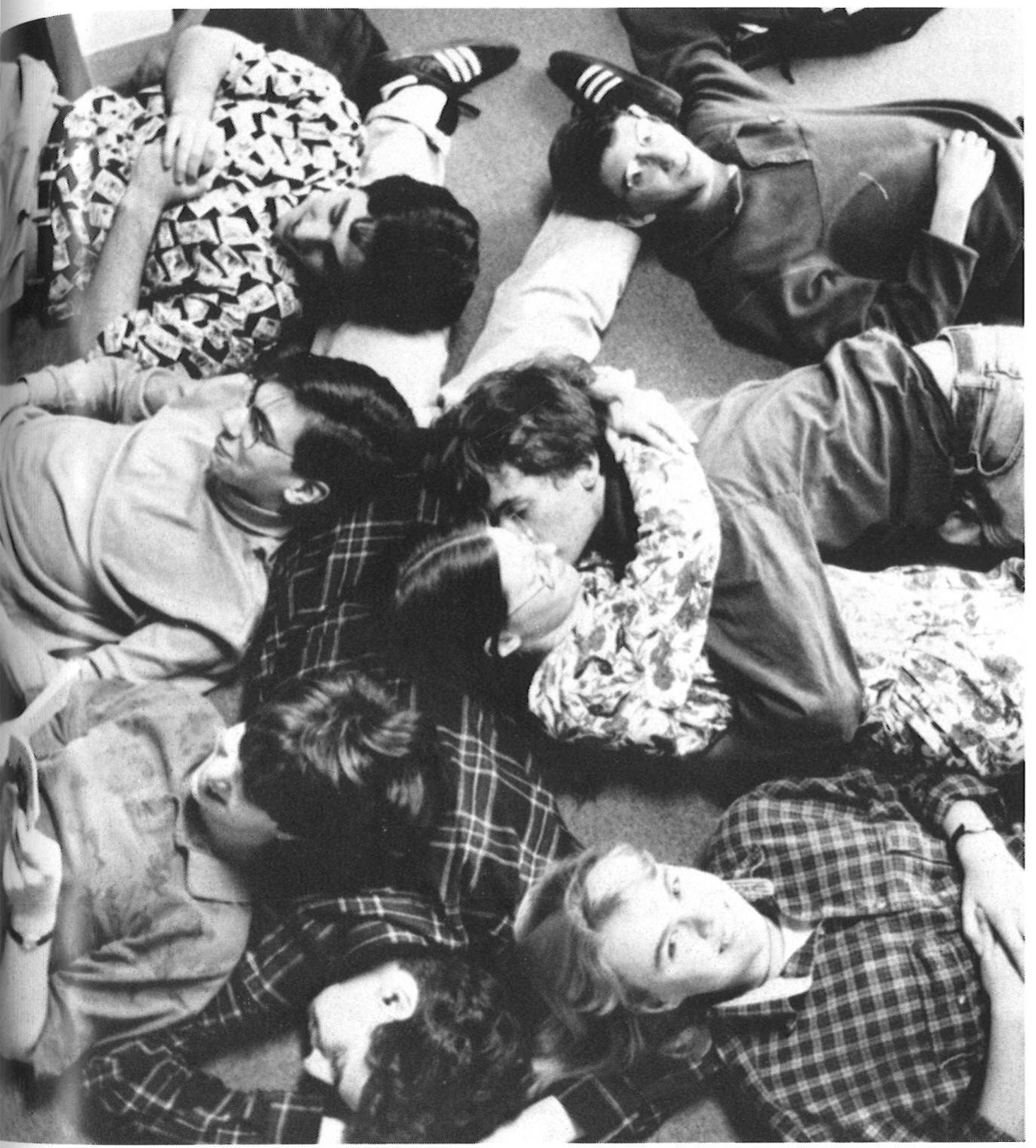

Kirsten Siebach shares her story at the Public Media Commons in St. Louis, MO in September 2023. Photo by Michael Thomas.

My planetary science advisor came and talked to me and said, “Hey, there's a mission that's gonna go land on Mars this summer, we hope. About 50% of them actually land. Hopefully, it lands in May, just a couple of weeks after classes end. And NASA is looking for a few more students. We need people who will take notes during mission planning so that NASA has a long term record of what we did on Mars and why we did it.”

I was like, “Well, I kind of like a little more certainty than a 50% chance of landing. This mission's in Tucson, Arizona. And Alaska sounded pretty exciting.”

He's like, “Kirsten, Mars missions do not land every year. You got to go give this a try.”

And I said, “Okay, what does it look like? What does this really entail?”

He's like, “Well, you'll be taking notes.”

I'm excellent at that. That I've got down. I've been in college for a whole year. I know how to take notes.

He said, “Okay, well, what's gonna happen is that this lander's gonna land on Mars. It's gonna work during the day. That's when there's light, and it can take pictures and things.

But we can't really operate it minute by minute because there's a 15 minute time delay. It takes 15 minutes for the speed of light to go from Earth to Mars.

So you've got this 15 minute delay, so what we have to do, instead of telling it what to do and going back and forth, we have to send it all its instructions for the day, first thing in the morning. It takes pictures, does chemistry, scoops up the dirt, does stuff all day. It sends us back all that data at the end of the day. And then it goes to sleep overnight.”

I'm like, “Okay.”

“So we're going to work Mars nights, getting all that information, and then figuring out what to tell it to do the next day and send up those instructions in time for the morning. And your job is to take notes on our meetings.”

“Okay.”

“Okay. There's one more complication.” He's like, “A day on Mars is 24 hours, 39 minutes and 15 seconds long.”

“Okay.”

“So we'll be working in Arizona, but because we're working Mars nights, our shift will slide about 40 minutes later each day.”

And I was 19. I thought about that, and I was like, “Well, you know, if I'm not paying attention, my bedtime slides later every day, and I frequently want a little more time in every day, so I think that'll be fine. I don't think that's an issue at all. Let's go.”

Kirsten Siebach shares her story at the Public Media Commons in St. Louis, MO in September 2023. Photo by Michael Thomas.

So we get to the end of school year, we go down, we fly down to Tucson, we're a few days before landing. It's my first time not at home or at college, so I got to go to the grocery store and figure out how to make food or get food. I buy a bunch of frozen food, and he's like, “Don't stock up too much. We don't know if it'll land.”

So I get some food and then we go to this kind of long term stay hotel. And we had to go buy tinfoil and put tinfoil over all the windows so that if we were sleeping during the day and night, it would be dark.

Okay. I'm getting pretty excited. This is real.

We go over to the Science Operations Center. We get to meet the science team. There's all these professors and scientists. It's this really cool team of people. It's this beautiful building with a building size mural of the Phoenix lander landing on Mars on the outside.

That was when I started to get really excited. “I'm going to be part of this project. We're going to land on Mars.”

The day of landing, we're with the whole science team in that Science Operations Center. Nobody has any control over the landing. We're just going to sit in arranged seats and kind of cheer it on, because it takes seven minutes to get from the top of the atmosphere to the ground and it takes 15 minutes for us to hear about it.

So we're not going to be able to quite follow that, but that meant that I had just as much control as everybody else. I was totally in. And we were all in and all of our summer job depends on whether or not this rover, this lander lands on Mars. Some of them had been working on it for eight or 10 years, and I'd been there for three days, but I was fully on board.

So we just waited. And those seven minutes, they call them the seven minutes of terror, as you're getting that signal back, you're just anxious and pacing and your heart is racing. And everybody's there looking at each other, nervous, waiting, waiting.

It landed perfectly. We were on Mars. It was real.

It sent back this nice, fuzzy little black and white picture with a dust cover over it, so it's this fish eye lens. I couldn't tell what was happening but there was sky and ground and that looked good. So we were ready to get started.

Our first shift started at 5:00 PM in Arizona. We go, everyone's sitting around the table. All these scientists and these big guys are all sitting around the table and I'm kind of sitting to the edge. I've got my laptop.

I'm like, “Okay, this is the part where I just take notes on what they say. Ready to go.”

They start going around the table and their first thing is that they go around the table and they tell everyone the status of all the instruments based on what's come back from Mars. They started talking and it turns out I didn't speak that language. Turns out you can make entire sentences out of acronyms. I didn't know which letters they were trying to say and pronounce into words. words.

Then I remembered I had an acronym guide. There was a website they told me about. So I go to the website and I start looking them up.

Well, it also turns out that every three letters can stand for three different things. So I just didn't know what they were talking about.

They went around the room. I kind of scrambled after that meeting, reading acronym guides. We went to another meeting. They go around. They're trying to arrange what happens next. It's another set of acronyms. This language continues.

Even when they were talking about the pictures that came back. I'd had one, two geology classes. I didn't quite understand what they were talking about either.

So I went home. I realized that, at that point, I couldn't call my family or friends because all of them were asleep. It takes some calculating. Like, “Oh, this is what? End of work. Nope. It's 3:00 AM, 4:00 AM. Okay. Well, sleep for a while and figure it out tomorrow.”

I sleep for a while. The next day, we start an hour later. Go through the day. Definitely still not understanding the words they're saying. Getting a little bit nervous.

It was about the fourth day, so imagine four days of hour of jet lag every day. It's 3:00 in the morning. I'm in my fifth meeting that day and I'm realizing I'm really not sure this job is for me. I really don't speak this language. This room is starting to smell like coffee and socks. It's 3:00 in the morning. These people are a little bit quirky. I am just not sure I'm in the right place.

I'm not a quitter. I'm very organized. I know what I'm doing. I did not know what I was doing. But I decided that I wouldn't let myself quit.

I said, “Okay, what you can do is if it reaches…”

With 40 minute delay every day, it takes about a month to rotate to the same start time for your job. So I said, “All right, if we get around the clock and we get back to that 5:00 PM start time, and I still don't know what they're talking about, that's when I'm allowed to quit. If I still feel like this, if I still can't talk to my family and friends, if I haven't figured out how to cook, we're just out at that point. I will have called it a good shot.”

I said, “All right. Between now and then, I still can't talk to anybody. I'm gonna just focus on this. I'm just going to put all of my effort into making these notes really pretty and trying to figure out what acronyms they're saying.”

Kirsten Siebach shares her story at the Public Media Commons in St. Louis, MO in September 2023. Photo by Michael Thomas.

And my go to in school and in life, perhaps, is color coding, like my inbox is color coded, my closet is color coded, like the Skittles are color coded before I eat them. It's my go to, so I just started doing that.

Got all the instruments. I put them all on spreadsheets. I had this nice rainbow spreadsheet with each instrument and each day. What was it doing? What were we going to do next? What was the plan?

And somebody walked behind me when I was taking notes, and they said, “What is that?”

I was like, “Well, this is my spreadsheet for keeping track of everything going on.”

They said, “Hold on, that's really useful. Like nobody here knows what's going on. Can you project that?”

So from that day, my laptop was the one projected on the screen in the front of the meeting.

And, suddenly, all of these scientists and professors that I had been looking way up at were coming to me to explain how to move the colored squares around so that I would accurately represent what they wanted to do on Mars and why and what was coming next.

I got to know them and I got to see that at 3:00 AM everyone is who they are and these people are nice. They're quirky, but we can all work together and we can all bring our color coding selves to this job and we can be a team and drive a lander on Mars.

And just being part of that, I have been so excited. I've ridden that wave. I'm still working on Mars 15 years later. However, at this point, I do usually insist on working on Earth time.

Thank you.

Part 2

It was the first day of sixth grade. I got out of my mother's brown Oldsmobile and walked onto the cracked, green asphalt at my middle school. I looked down at the feet of the other kids there and I realized something shocking. I was wearing the right shoes. They were those brown Eastland loafers. And if you were 12 in 1987, they were totally mandatory.

I didn't have it all right because I didn't have the laces tied into those little curly cues, but, still, they were the right shoes.

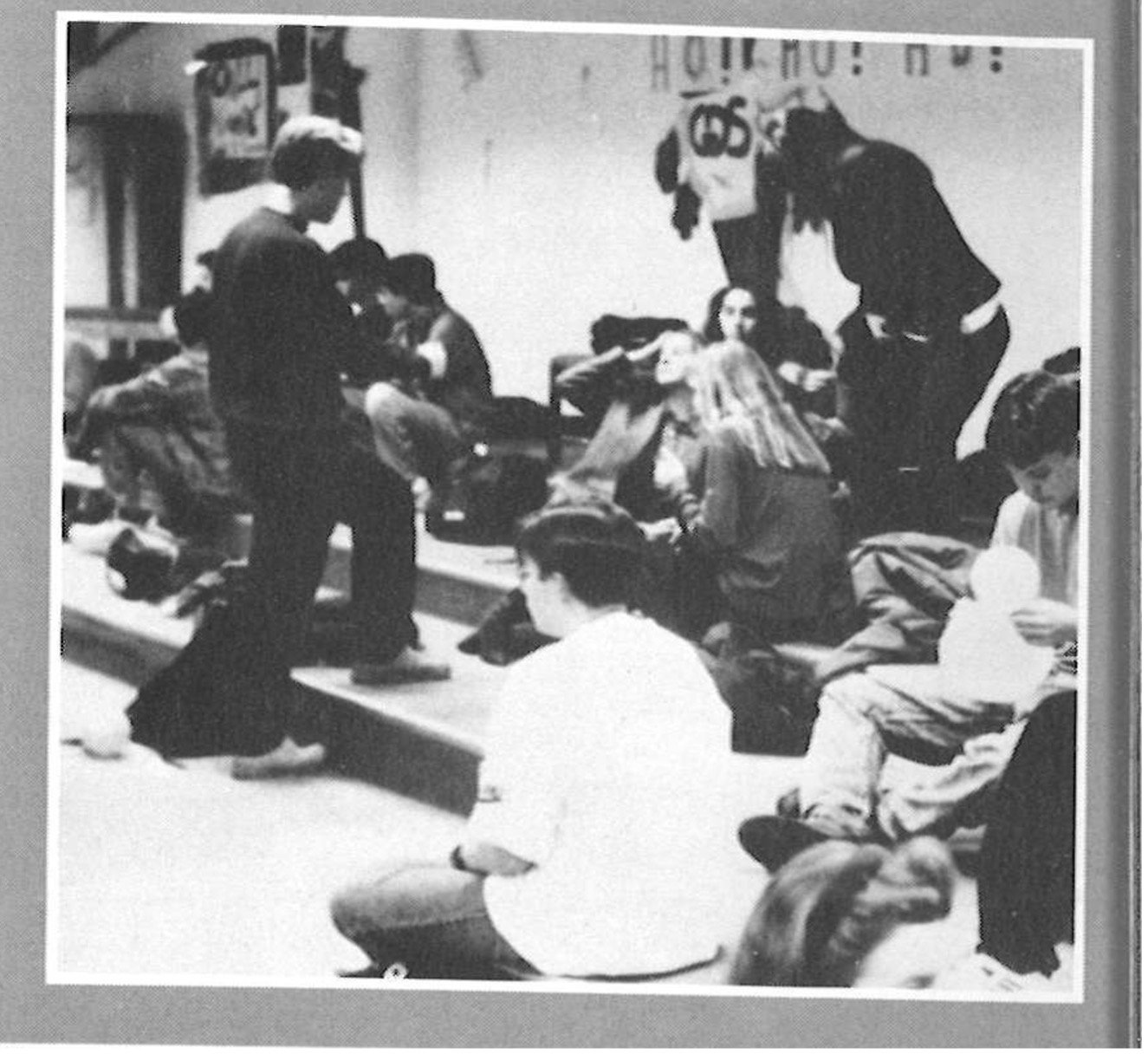

Alison Spodek shares her story at Caveat in New York, NY in October 2023. Photo by Zhen Qin.

This was kind of shocking because, for most of middle school, I got everything wrong. I had the wrong hair and the wrong face and the wrong body and the wrong attitude. Luckily, by the time I got to high school, the definition of right and wrong had expanded a little bit. There were actually a lot of ways to be right so long as you had your people and your place.

In my high school, your place was really literal. We are defined by where we hung out. So, there was a student lounge, but the only kids who lounged there were the ones who knew they belonged wherever they went. The kids who had been right all through middle school.

There were a group of athletes who hung out near the gym and there were some theater kids near the lighting booth. Over time, I found myself gravitating to a group of kids who hung out at the far end of the third floor. We were kind of the odd socks and it really was never clear what drew us together.

We had one kid who was a baby hacker, a talented oboist, someone who published a ‘zine, and a couple of stoners. We wore a lot of black eyeliner and a lot of tie‑dye t‑shirts.

And we've grown up to be really different people. The baby hacker has turned into a tech millionaire. We have someone who's become a Buddhist monk. And through all of this, I really didn't know what unified us.

There was another group that I really wanted to be a part of. This was a group of kids who hung out in the lobby of the high school, underneath a 9‑foot by 12‑foot painting of Albert Einstein. Naturally, they called themselves the Einstein Posse.

There was a subtext to that. Even in a pretty competitive high school, these kids were geniuses. They've grown up to be world‑renowned mathematicians, prominent philosophers, editors of major national publications. I looked at them and I knew exactly how they were right. They were smart. I mean, I wore eyeliner and had quirky friends. They were smart.

So, this desire to at least appear smart really wormed its way into my heart. I remember at one point leaving a Spanish test after about 20 minutes and I was pretty sure I had aced it. I felt really smug. But I wasn't smug because I thought I'd aced it. I was smug because people were watching me leave the room and they thought I was smart.

So that desire to appear smart, it started to guide my choices. It's part of why I majored in chemistry in college, why I worked as a research chemist for a few years, and then why I applied to graduate school for physical chemistry. I got accepted to Yale and then I accepted that offer. This was it. Proof I was smart.

Alison Spodek shares her story at Caveat in New York, NY in October 2023. Photo by Zhen Qin.

But before I started the program, my boyfriend and I, we decided to travel for a little bit. So, we rode our bikes down the West Coast and then, when we got there, we realized we didn't really want to ride them across the Rocky Mountains, so we took Amtrak all the way over to Jacksonville, Florida.

Side note, I do not recommend that.

When we got there, we rode up the East Coast and we stayed in churchyards and in people's RVs and on houseboats and in more campsites than I can possibly count. We stayed for two weeks at a hostel that had a geodesic dome in all the rooms and treehouses. Even if Amtrak was pretty terrible, the trip as a whole was amazing.

But that's where my doubts started to come in. After all, if I could be this happy without anybody thinking I was smart, did I really need to go to Yale?

The thing is, I've never been such a flexible thinker, so I just pushed down my doubts and started the program. And the classes were okay. It was another opportunity to prove that I was smart, show my professors. And then the research started. I would look at the stack of papers about the work I was supposed to be doing and then I would look at the laser that I was supposed to be doing the work with and I saw no connection whatsoever.

I hated it. I procrastinated. I avoided it. Finally, I let go of needing to look smart and said, "I need to leave this program."

So, now, I have no job, no money, no career plans, no fancy graduate program, just this awesome boyfriend, who turned into a fiancé by this point.

We moved to New York City where I saw a sign on a street post that said, "Want to make money while saving the environment?"

And I thought, "Sure, that sounds pretty good." So I started to work for Greenpeace.

And if you lived in New York in the early 2000s, you would have seen us, the little Greenpeace shills. We traveled in flocks of four and we stood on street corners and stopped everybody who walked by and said, "Hi, do you have a minute for Greenpeace?"

My goal was to sign people up as a sustaining member who would make a monthly donation to the organization. Basically, I got paid $15 for every person who would give me their credit card number on the street. It wasn't a scam, but it wasn't Yale either.

It turned out I was pretty bad at measuring the quantum mechanical properties of water with a laser, but I was actually a pretty good salesperson. So I was feeling pretty good about myself, smug even, and I was stationed one day in July in Midtown.

Now, Midtown's a pretty hard place for this kind of work because, after all, all the businessmen and office workers do not have a minute for Greenpeace.

It had been kind of a long hard day and it was about 5:30 in the afternoon, but the deal with this job was you just kept trying. I saw a man walking towards me and he was wearing a gray suit and I just put my best saleswoman smile on and said, “Hi, do you have a minute for Greenpeace?’

He looked at me and said, “Alison?”

Oh, shit. It was a member of the Einstein Posse.

So I pulled myself together and I said, “Wow! What are you up to?”

“Oh, I'm just coming from my job at this big publishing house.”

“Cool.”

“Yeah, I'm also working on my novel.”

Side note, this novel went on to become a New York Times bestseller.

Then he said to me, “So what are you up to?”

“Well…”

We made awkward small talk for a few more minutes and he wasn't rude at all, but he didn't know what to say.

So then he said, “Okay, I guess I should let you get back to recruiting,” and walked away.

Side note, I did not sign him up as a sustaining member of Greenpeace.

Heading home an hour or so later on the 1 Train, my overwhelming feeling was one of embarrassment. I had run into a member of the Einstein Posse. And here I was in my Greenpeace t‑shirt, frizzy hair, no real career plans and he was an adult. He was living life right. What was I doing?

Alison Spodek shares her story at Caveat in New York, NY in October 2023. Photo by Zhen Qin.

But then as the train continued to rattle north, a new feeling kind of emerged. It was the feeling of liberation. You know what? I wasn't a member of the Einstein Posse. I was a member of the third‑floor weirdos.

I realized what really unified us was a willingness to explore, everything from Buddhist spirituality to the emerging internet to 96 hours on Amtrak. I still had no career, no fancy graduate program, no proof I was smart, just this awesome fiancé who I loved. Maybe I was doing life right.

In the 25 years since then, I've really tried to explore and assemble a life that actually makes me happy, that brings me meaning. It turns out it involves some black eyeliner in dance clubs, involves some tie‑dye t‑shirts in music festivals, and it involves a lot of travel and adventures and love. It also involves environmental science, a science I had never considered when my main consideration was appearing smart.

Environmental science has taken me everywhere from the deserts of Oman to a super fun site in New Jersey. It turns out, it's the perfect science for this third‑floor weirdo.