CDC research shows about 1 in 8 women with a recent live birth experience symptoms of postpartum depression. In this week’s episode, our storytellers share their experience with postpartum depression.

Part 1: With a new kid and her husband moving to Iowa for a job, Angie Chatman’s mental health begins to suffer.

Angie Chatman is a Pushcart Prize nominated writer, a voice over artist, and a WEBBY award-winning storyteller. She’s told for The Moth Radio Hour, World Channel/GBH’s Stories from the Stage, Fugitive Stories, and Story Collider. A Chicago native, Angie now lives in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood where she identifies as a married Mom to grown folks and a rescue dog, Lizzie.

Part 2: Anna Agniel’s romantic notions of married life with a child are broken when her husband relapses and her son is born with a cleft palate.

Anna Agniel, a storyteller since childhood, studied theatre, playwriting, and solo performance at SMU's Meadows School of the Arts. She toured her one-woman show, Slow Children Playing, around the country, and in 2019 founded her own business, Storiespeak, to encourage other people to write and tell their stories. Anna now works as the Senior Associate Director of Class and University Programs at Washington University in St. Louis, and she utilizes storytelling and creative producing skills both at work and at home with her three children.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

I'm three months pregnant and 42 years old. I'm really excited about being pregnant with our third child, because my hair is growing luxuriously, I can eat whatever I want and I feel really good. My doctors, on the other hand, are kind of nervous because I'm a black woman, in case you hadn't noticed. And black maternal health is high risk, especially if you're over 40.

But I ignored them, because I have something else that's on my mind, and that is that my husband is about to lose his job. We know already that his division at the company is going to be sold someplace else. He'll get a nice payout and everything, but those don't last forever and babies do.

Angie Chatman shares her story at Turtle Swamp Brewing in Boston, MA in May, 2023. Photo by Kate Flock

Fortunately, they already announced it and everything so he's looking really hard for a job. And he brings this description of a job that he wants to me. I scan it for the most important information there is, location.

See, we have moved already a couple of times in our marriage and I wanted to settle with our children in this house that we had built for us. But what can you do? He needs a job. We have three children.

It says on the sheet ‘Somewhere in the Midwest’. I know right away that that's not Chicago, because recruiters on the East Coast are familiar with that New Yorker magazine cover where they look out west of the United States and all they see is Chicago and then LA.

So, I think to myself, “Well, Minneapolis, Mall of America, that's gonna be okay. Omaha, Warren Buffett territory. Anytime there's a billionaire in a town, it's going to be okay. And Kansas City, blues, jazz and barbecue. Okay. Great.”

He comes back after the initial interview and he says, “It's in Des Moines.”

“Iowa? I don't want to go to Iowa. There are no black people there.”

Every time you see the caucuses and the presidential candidates on the main road of the Iowa State Fair shaking hands, I dare you. I'm sure there's only one black person on that road and he was put there for just to pretend Iowa has black people.

And so, I'm like, “No, I'm not going.”

And my husband is like, “What? Huh? What? What do you mean you’re not going?”

And I'm like, “Well, I just had this baby. She's wonderful. And I need to stay here in Connecticut till I'm past the six‑month mark with the child, because I don't want to be looking for new doctors and somebody to check my health and everything. So, you go ahead. Send money and we'll be fine.”

My husband's not a fool and he knows me, and so he took our oldest son, our oldest, Adam, with him to Iowa as captive. I don't care. Boys can live there. Me and the two girls can live here. It'll be fine, because I'm not going to Iowa.

Time passes and I start to get really depressed. So, I call my mother, because, on the one hand, I am missing my son and my husband a little bit, but I'm exhausted, because I have my older girl who still has to go back and forth to school and then this baby. So, I call my mother, crying on the phone. And I call my mother the next night, and I call my mother the next night.

Finally, my mother says, “You know, you need to see somebody. I can't listen to this all the time. You know you're gonna have to move. You have to have your family together. Just swallow it and get on with it.” And she said, “And, you know, since you've been crying every night, do you cry during the day?”

And I said, “Well, sometimes.”

She's like, “Yeah, that sounds like postpartum depression. Maybe you should go see your doctor.”

So I'm like, “Okay, that's a good idea.” I am tired of using all these Kleenex and throwing them out at the end of the night.

Angie Chatman shares her story at Turtle Swamp Brewing in Boston, MA in May, 2023. Photo by Kate Flock

I called them and so I got the nurse practitioner. She asked me two questions. She said, “Do you have any thought of hurting your baby?”

And I said, “No, she's really cute. I like her.”

“Do you have any thoughts of hurting yourself?”

I paused for just a moment, and she said, “I want you to come in right now.” I did and they gave me some medicine and I felt better, but I was kind of worried because I was breastfeeding and I didn't want my baby to have any drugs. I just wanted her to have my nutritious milk made specifically for her.

So, I called my mother again and told her what happened and everything.

And she's like, “Well, I work so I can't be up with you all night listening to you cry. So, what you should do is don't you have a church home? You should go see your pastor.”

And I'm like, “Oh, yeah, that would be nice. Okay, I'll go over there.”

So I called her, I made an appointment. We sat, we had tea and cookies and she listened to me. She listened to me whine about the situation and how I really didn't want to move to Iowa. She just nodded her head and she said, “You know, do you know Lori?”

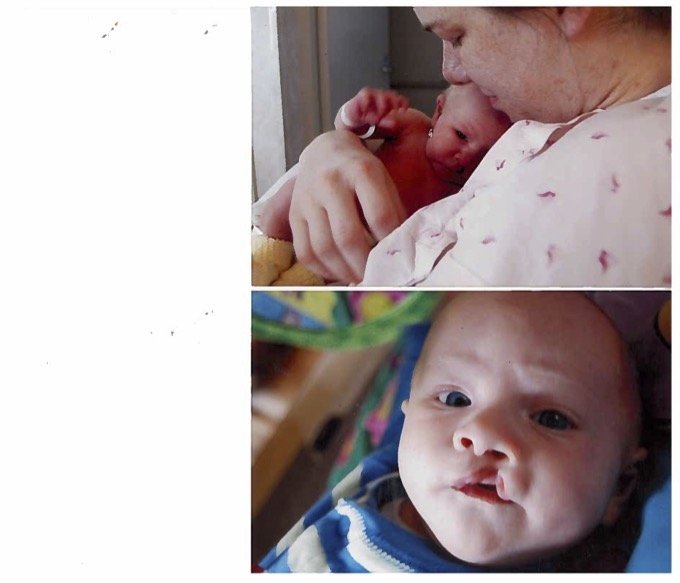

Angie with her new baby and her two other children. Photo courtesy of Angie Chatman

It's like everybody in the church knows Lori. Lori had stage three cancer and she survived.

I said, “Well, yeah, of course I know Lori.”

She's like, “I want you to talk to her.”

And I'm like, “Okay. That wasn't what I expected you to do but I'll follow your directions.” I thought she was going to give me some scripture to read or something like that.

So, I went down to Wesleyan where Lori was working and she took me out to lunch. She told me her story about cancer and how the only way that she beat cancer was to change her life. She had to eat differently. She had to work less. She had to exercise.

And she said, “All of those things were really hard for me to do, but I did them because I wanted to live. And, actually, what I learned from that is whenever God gives you a change that you don't want, think of it as a gift. Don't complain about the wrapping paper.”

Angie Chatman shares her story at Turtle Swamp Brewing in Boston, MA in May, 2023. Photo by Kate Flock

So, I went home and I thought about it and everything. Meanwhile, my husband had another card up his sleeve where it's now getting towards Christmas. He had our son call me and say, “Mommy, aren't you and Tina and Annette coming to Iowa for Christmas? How will Santa find us if we're apart?”

So, we came for Christmas and we stayed for just a little while. That's what I told him. “I'm only gonna stay for a little while.”

We ended up staying the whole time. Sold our house from afar and I actually liked Iowa. I could get my hair done. There were black people. The reason why they weren't on the Midway at the State Fair is because they had been going to the State Fair since the time they were two years old and they got tired of it.

I made friends, I had community, and so, now, whenever another change comes upon me that doesn't feel quite right, I tell myself, "This is a gift. Stop complaining about the wrapping paper.”

Thank you.

Part 2

A dyad is the smallest relationship possible in sociology. Dyads you might hear about are the doctor patient dyad or the mother baby dyad. And 13, 14 years ago, I found myself in a marital dyad, which I had romantic notions of what that would be like to be newly married, but it was much more difficult than I assumed because my husband battled addiction.

We saw a therapist at the time who said to us, “Someday, you will be grateful for this experience.”

And I thought, “You gotta be kidding me, lady.”

A couple of weeks after that appointment, we had our first child. And in the buildup to that, we had this amazing team building experience of taking Lamaze classes together. So, whatever grief was in my heart, really, was softened by the experience of going through Lamaze classes with my partner, talking about how we would make it through labor and delivery and welcoming this new person into the world.

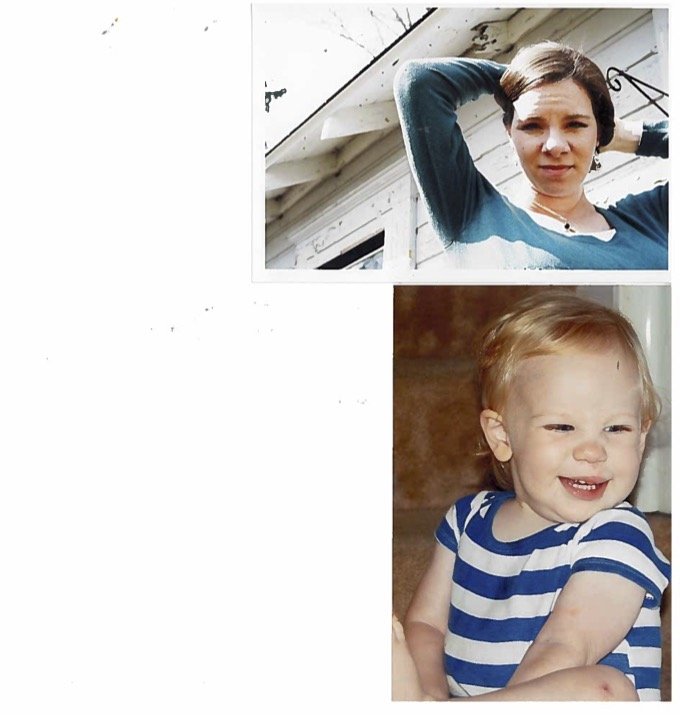

Then, in the labor and delivery room, our son, unbeknownst to us, was born with a cleft lip and submucous cleft palate. So, as we are dealing with this brand new life, we are also trying to fathom what happened in utero that led to this cleft lip and cleft palate.

A couple of weeks after that, my husband and I are having this back and forth of who is doing more of the night work. Who's waking up more at night with the baby? I say to him, “It seems like, over the past couple of weeks, it's gotten more difficult to wake you up.”

Anna Agniel shares her story at the Public Media Commons in St. Louis, MO in June 2022. Photo by Michael Thomas.

And he says, “I told you, if you need my help, please just wake me up.”

When we'd first come home from the hospital, we had been an amazing tag team. Our dyad fully intact, working back and forth in handing that baby off. But something had changed. That's what I was trying to get at with him.

I said, “Something is different.”

And after a long pause, he said to me, “There's something I need to tell you. I need you to get the painkillers out of the house.”

I didn't know exactly what he meant until I realized I had been prescribed painkillers after labor and delivery. So, I went and I found the pill bottle and realized it was greatly diminished. I hadn't been taking them.

I brought it to him and I said, “There's a lot missing from this bottle. Have you been taking these?”

And he said, “Yes.”

In that moment, a door opened inside of me and out flew rage. But because our infant son was asleep, and he rarely slept, because he was asleep and because I already knew what my husband was going through in battling his own addictions, I said nothing except, “I'm leaving to take these somewhere. I will be back to feed our baby.”

I got in the car and I started driving thinking, “Where am I gonna go with these pills?”

I called my parents and, for a moment, I thought, “Maybe I will tell them what's been going on.” Instead, I thought, “No, I'm going to swallow this story for just a little bit until I can figure out what's going on.”

So, instead, I chatted with my parents. I thanked them for having us that past weekend. We had just come home from a trip. And got off the phone with them and continued driving and crying and trying to find a place to throw away these pills.

Thankfully, I found the most disgusting dumpster possible outside of a Walgreens and dumped the pills there and returned home a little later to see my husband sitting on the floor. He looked like he had been crying, clearly overwhelmed and lost.

And instead of me joining him there in his overwhelm and his loss, I sat across the room from him and I said, "I need another adult to help me raise this baby."

From that moment on, I made a choice. Now, whether it was conscious choice or unconscious choice, I made a choice to start building a very succinct and efficient wall to hold back the emotions that were rocking my world.

What that looked like, the way that the brain was working in a postpartum world was to become highly organized, which I already was. I'm a high functioning, anxious person. I'm on time for everything. I am extremely punctual, organized and put together. While on the inside, there is hyper critical and self doubt going on.

So, I'm building these like sandbags to keep back the wall of emotion. We did cloth diapers. We made all of our baby food from scratch. My husband had a rigorous schedule of trying to get a PhD and I was putting him through school. I returned to working full time, sometimes 13 or 14 hours a day, while pumping and trying to get breast milk home to our baby.

This was a grueling pace and yet I wouldn't let up. I just kept stacking those sandbags, thinking the way to deal with this stress is to take good care of these two other people that I love.

Anna Agniel shares her story at the Public Media Commons in St. Louis, MO in June 2022. Photo by Michael Thomas.

Now, I also thought, to be a successful mother, I would keep our baby healthy. A child with a cleft lip and submucous cleft palate is very difficult to keep healthy, because he had recurrent ear infections, constantly sick. He caught the dreaded H1N1, which, at that time, was the plague dominating the news. It was impossible to get this baby to be well. He had extreme reflux, so every time we would feed him and he would struggle to eat, he would then throw it back up.

I kept apace thinking this is the way to keep my family safe and together. I even joined a 12 step group on my husband's suggestion, because he could see how anxious I was. And I joined the 12 step community but I thought, “I don't need anybody else. I mean, I don't have the problem here, so I'll go ahead and join this group but I'm really okay and I don't need a sponsor and I'll work the 12 steps by myself.”

By the time our son turned one and I was keeping this pace, keeping those dyads as healthy as I could, there was one Saturday morning when I had a random quiet morning to myself. My husband had just left to go to the farmers market, our son was down for a nap and all I could think was there was no rest in sight.

For a moment I thought, “What if I just walk out that door and never come back?” Then I set that thought aside and I went to do the morning dishes. And as I was doing the dishes, I started to see in my mind's eye an image of my wrists being cut. Though this terrified me, it also equaled a release, a terrifying release. But I set that aside and I just kept going.

That image of my wrists being cut stuck with me for a couple of weeks, to the point that I started fearing the knives in our kitchen. One night, we're going to sleep. The lights are out, our son is sleeping through the night, by this point. And I say to my husband, "It's gotten really dark for me."

And he said, "What do you mean?"

And I said, "I just sometimes I'm not sure it's worth it and I've started to fear the knives in the kitchen.”

And he said, "If you have that feeling in the middle of the night, will you please wake me up?"

And I thought, I mean, that's a compassionate thing to say. But also, he was a hard person to wake in the middle of the night. We already knew this.

The next morning our son had yet another medical appointment. I had another long day of work ahead of me. We were getting our son ready for yet another surgery. And as I dropped our baby off with the nanny, she looked at my face and she could tell I was struggling.

She said to me, "What's going on?"

I said, "I'm having a rough day."

I handed her our son and she was holding him in her arms and I started to cry. Our sweet son reached over and wiped one of my tears off of my cheek. Then he rubbed it in his fingers and then he wiped it on his shirt, and I cried more.

I said goodbye to them and I got in the car and I called my mom.

I said, "Mom, it's gotten really dark.” My mom is a nurse, so my mom flips into a very medical mind.

She said, "Tell me what you mean."

I said, "I've started to feel like it's not worth it to live and I've become really afraid of the knives in the kitchen."

And my mom said, "Do you have a plan? Where are you right now? Talk me through where you're going and I'm gonna call some people and I'm gonna call you back. And I will make sure you are where you are when I call you back.”

This began a cascade of events, like that dam that I had built up for myself. Everything started to push over the dam. My mom called my husband. My mom called my dad. My mom called my sister in law to find out who could come support me.

We ended up going to the ER that day, being checked out by some doctors who then sent me on to a psychiatric facility to find out if it would be better for me to have inpatient care, which meant it was a long, long day.

As we got to maybe 10:00 at night, a short African man came out, the doctor. Said, “I'd like to speak with you.” And I thought my husband would come with me back to this room. The doctor said, “No, he has to stay out here.”

This felt jarring. It felt like this is my dyad. You can't take my dyad from me.

Anna Agniel shares her story at the Public Media Commons in St. Louis, MO in June 2022. Photo by Michael Thomas.

But we get back to this room and the doctor and I talk for a long time. He had a thick accent. I was explaining to him everything that had transpired in the year, from the addiction and the recovery and the relapses to me trying to care for my husband to caring for a baby with high medical needs who was constantly sick, a working job that I just couldn't quite keep up with anymore.

The doctor finally says to me, “You are afraid of your marriage.”

For a moment, I thought, “Maybe this has been lost in translation.”

I said, “No, I'm not afraid of my marriage. My husband does not physically harm me.”

And he said, "No, no. You are afraid of your marriage ending."

And at that moment, the doctor sliced right through my dyad and stood between the two of us and helped me to refocus what exactly I had been doing.

I began to cry harder and I said, "Yes, I am."

And he said, "You have a baby at home, right?"

And I said, "Yes, I do."

Again, he stepped right into that mother baby dyad and refocused me. And he said, "If I let you go home tonight, you are gonna go take care of that baby, right?"

And I said, "Yes, I am."

And he said, "I believe you."

And with the doctor's belief in me, I could suddenly, for at least 12 hours, believe in myself that, for 12 hours, I would not hurt myself.

That doctor and I, we made a plan for the next day for me to see a primary care physician. For me to begin regular, consistent therapy, to possibly start medication. But what he did for me that night when he sent me back home was he sent me back home with the belief that I could still participate in these dyads, but I needed to participate in a different way.

I had a huge road ahead of me. Therapy for me, therapy for my husband, therapy for us together, still raising a baby with a mountain of issues ahead of him. But I began to understand something different about dyads. And I think that, perhaps, sociologists have it slightly wrong, because the smallest possible group for us humans is not that mother baby or that doctor patient or that spouse and spouse. The smallest possible group that is most important is the relationship that I have with myself. I am only as good in that dyad as I am with who I am myself.

Thank you.