Memories are the threads that weave together the tapestry of our lives, each one a cherished treasure that shapes who we are and where we've been. In this week’s episode, both of our storytellers share stories about memories that altered their lives.

Part 1: After constantly living in the shadow of her older sister, RJ Millena isn’t sure how to carve her own path.

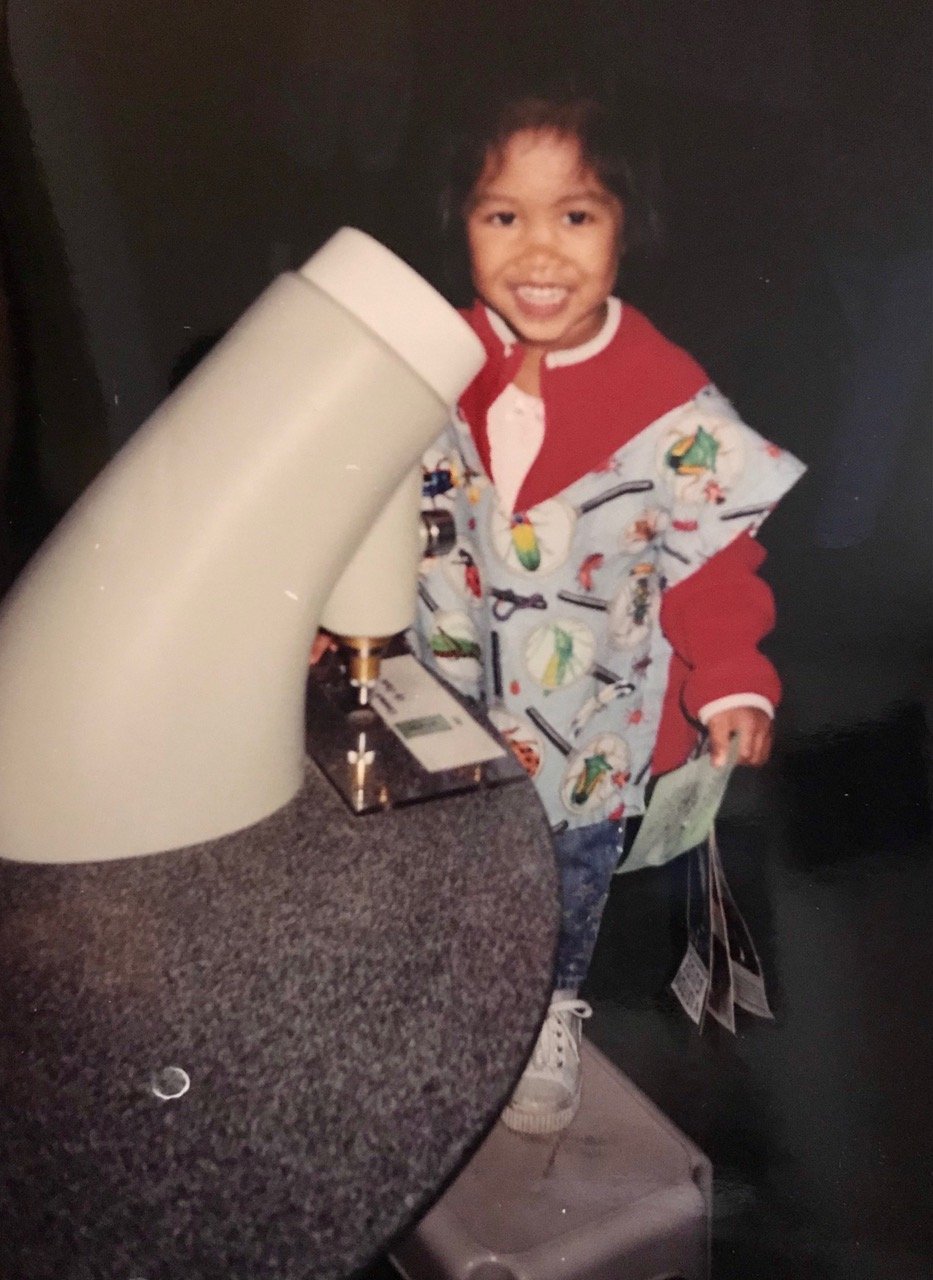

RJ Millena is an entomologist specializing in the evolution of the twisted-wing insect parasites (Strepsiptera). She is currently a PhD Candidate with the Ware Lab in the Comparative Biology program at the American Museum of Natural History's Richard Gilder Graduate School. Originally from California, RJ grew up in the East Bay with her parents, sister, and large extended Filipino family. She attended UC Davis for her undergraduate degree in Entomology, with double minors in Nematology and Ecology, Evolution, & Biodiversity. In her spare time, she enjoys insect and turtle husbandry, playing drums and trumpet, dancing ballet, and flying trapeze with her sister. Her favorite insect is the one she studies, and her least favorite insect is the bedbug.

Part 2: When Jasmine Anenberg finds out her high school friend overdoses while she’s working in the field, she starts to see the world differently.

Jasmine Anenberg is a current PhD student in the School of Forestry at Northern Arizona University. She originally hails from San Jose, California but has lived all over the west and is happy to now call Flagstaff home. She received her Bachelor of Arts in Geography and Minor in Botany in 2014 from San Francisco State University, and has worked across many sectors from urban gardening nonprofits to coffee shops to ecological restoration with federal agencies. Her research interests include plant and soil ecology, biological soil crust restoration, and dryland ecosystems. When she is not doing science, Jasmine enjoys rock climbing, hanging with her dog, and volunteer DJing on community radio.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

I am a younger sibling, as many people are. I am one of two daughters, the baby. Two daughters that our parents raised. My older sister is named Rachel Lee and I'm Rebecca Jean or, more commonly, RJ.

We are two years apart. As many siblings with close age gaps or no age gaps do, we are often grouped together by our parents. They pushed us, they pulled us, too, in tandem strollers. They dressed us the same. They grouped us into the same activities like piano, ballet, and golf. And they expected us to share the same interests and standards.

To my family's surprise, though, I started displaying this obsession with insects from a very young age. We have proof of this in my childhood bedroom at home-home, a kindergarten poster I made when I was six that reads, “When I grow up, I want to be an entomologist,” in the bottom left hand corner.

Besides this, I was basically a carbon copy of Rachel as a child. An extreme example of this that my mom likes to talk about is that I was born left handed, apparently, but at some point when we were writing or coloring together, I switched because I copied my right handed sister so much.

Because Rachel was older than me, she got to experience school first, so she set the bar in basically everything for me. We had all the same teachers, so they would usually slip up and call me by her name. Her friends joked that RJ stood for Rachel Jr. And our parents would measure me by how she had been performing at that age.

RJ Millena shares her story at Caveat in New York, NY in October 2023. Photo by Zhen Qin.

Because of this, most of my achievements were often overshadowed, or I thought they were. And Rachel shone bright. She won so many academic competitions at our school, especially spelling and geography bees. She even went on to place in the Top 10 in one of our county spelling bees and she was overall star student.

She perhaps blazed the brightest at age 10 when she was chosen as a contestant in Kids Jeopardy in October 2007, and absolutely wiped the competition, bringing home $28,000. It was at this point, I think, that the pressure that had always been poking at me became much more pronounced.

I ran crying one night from a family party after the airing, following all of that celebrating her win, when an aunt came up to me for like the thousandth time that night and went, "So, RJ, when are you auditioning for Jeopardy?"

At that point, my competitive nature skyrocketed. I decided I was going to try to be better than Rachel in everything. And if I couldn't, I simply would not try.

I especially refused to participate properly in the spelling bees, because even the thought of them made me sick to my stomach. I purposely failed out of the last qualifying round of our eighth grade spelling bee going on to like the real bee because I was simply so angry. That made my mother cry and I just couldn't do anything about it because I already did it. I wanted to be outside buzzing around with the real bees.

Accordingly, I was banned from our fourth grade classroom for bringing in too many insects that got loose, but we all had a good time, I think.

I was affectionately called her “Bug Lady” by my favorite teacher, Sister Maureen. She was a nun. And our eighth grade classroom had a class pet of a praying mantis because of me.

Regardless, my resentment of but also copycat behavior of my sister continued into high school and we added a whole bunch of new extracurriculars for me to try to out compete her at at that time: marching band, choir, and theater.

I thought I was getting a bit of headway, actually, at this point because I was starting to hear these arguments between my sister and my parents. Yelling matches through my bedroom walls about her grades. Instead of sympathizing with my sister about the pressure, the mounting pressure being placed on this gifted child, I rejoiced in thinking that it was my turn to be the golden child.

This all came crashing down in a couple years when Rachel was accepted to and then moved away to UCLA in Southern California to study theater. Suddenly, I was left behind without any guidance about how I should be acting, nothing to compare myself to on, basically, the entire basis for my personality.

I had an identity crisis. I acted out. I floundered and I engaged in some very unhealthy relationships. I wasn't engaging in my classes like I had before. My teachers noticed, so my grades were dropping.

RJ Millena shares her story at Caveat in New York, NY in October 2023. Photo by Zhen Qin.

One of the first high school relationships, if you could call it that, that I was in was with someone who had initially been fixated on Rachel. He even told me so when we first started talking and I managed to convince myself that I was into consolation prize.

We visited Rachel as a family in my senior year of high school and I got to stay with her in her apartment for fun sleepovers.

During this visit, Rachel was probably the meanest she has ever been to me in our lives. I could not eat anything but peanut butter sandwiches in that apartment, because I simply did not know what else I was allowed to make in her kitchen.

When our parents would join us during that trip, Rachel was volatile. I once asked her why she couldn't talk to our parents normally, why she was being so rude, and she snapped back at me, "You can talk to them. I can't."

I think I realized I wasn't the only one with resentment. And only by maybe breaking apart from our family and each other could we figure out who we were as people.

My college applications totaled five. One for theater, the exact same program at UCLA that my sister was in, one for music and three for entomology. When I was accepted to UC Davis for entomology, it felt correct.

I cried with joy. I did not even follow up with UCLA for the invitation to interview for that same program. I moved out of our childhood home with my head full of thoughts of insects and, finally, discovered who I was as an individual.

Entomology saved me. Simultaneously, Rachel was being saved herself by theater. She moved to Portland, Oregon to an apprenticeship with Portland Playhouse and we tentatively began to repair our relationship with the states’ distance between us acting as a buffer.

She would text me, “I miss you,” and I would text back, and I would realize halfway through that it was true.

In undergrad, I met the people that I know I will love for my entire life and who didn't even know like until two or three years into our friendship or relationship that I had an older sister, which is like nuts.

I also was introduced to the organism that I love and I've decided to dedicate the rest of my life to working on, Strepsiptera.

Strepsiptera, or the twisted wing parasites, are parasitic insects. Sorry for teaching you things. I know we're not allowed to be learning, but just forget this right after. They're this parasitic insect. They break a lot of different rules about what insect life should be, so I'm stoked about them.

The males and females look very different. The females kind of look like worms. They have this head capsule, but the rest of them is in a butt. So I like to call them the “Bug Butt” parasites because they parasitize things like bees, wasps, ants, katydids, crickets, you name it.

The males, however, they also develop in a bug butt but, at some point, they pop out of a pupal cap after a metamorphosis and they emerge and they fly away. They look like this. I'm showing my shirt. They kind of look like a fly. They have those little halteres, which are club like structures. But in the fly, that's the hindwing. In Strepsiptera, that's the forewing, and that's what's really weird.

RJ Millena shares her story at Caveat in New York, NY in October 2023. Photo by Zhen Qin.

They're also about the size of like a pin, because you can imagine them on other insects.

I often have bugs on the brain. Because of this, I like to think of my life in the context of insects. Sometimes when I think of my sister and me, I can think of myself like the female parasite. I could have been like her, never changing, really, or becoming anything more than what I am or detaching from the thing that's giving me nourishment. Instead, I think I've become more like the male. I've been able to go through a difficult but necessary metamorphosis. It's uncomfortable, but I'm here now. And I've emerged as something that's capable of flying away to find a new path.

An even more appropriate summation of our relationship, perhaps, is the last activity that's brought us together, trapeze. Rachel is actually, as of a couple years ago, a trapeze instructor in the Santa Monica Trapeze School in Southern California. We both regularly take classes and she was responsible for introducing me to this high flying activity that she knew I would love.

This past August, I visited her. I ate way more things than peanut butter sandwiches this time. She fed me so much food. It was really good. But we were able to fly together like we never had before, because now she's an instructor.

She took me, she literally sent me off the board 25 feet in the air to fly in the sky. She commanded my safety lines in another round and called out instructions as I was hanging by one leg from a bar. She hugged me tight as we dangled together upside down from a suspended hoop.

I think we're the closest that we've ever been now, even though we're separated by a literal country. We'll text each other all the time. We'll Facetime. We play Animal Crossing together. And she'll fly across the country to see me talk about her in this show.

I am grateful and happy to call her my sister.

Part 2

I'm in Montana. When you think about Montana, what do you see? Maybe some bald eagles flying overhead, grizzlies romping through the forest, rivers rushing. This is a majestic landscape and when I tell people that I do science in Montana, they get excited. But what does that really look like?

Jasmine Anenberg shares her story at Kitt Recital Hall in Flagstaff, AZ in September 2023. Photo by Joshua Biggs.

I'm a soil restoration scientist. That's a double whammy for unglamorous work. I look at uncharismatic and unhealthy dirt. When I'm at my field site, I'm on my knees and I'm hunched over in the most uncomfortable position and I'm trying to see these tiny, dusty, dried up mosses that are on top of the soil. They're so small that they're almost invisible.

My nose is pressed so closely that it's in the dirt. I'm sweating so profusely that I feel like I should probably note it on the data sheet, just in case. And my allergies are getting so bad from all of the plants around me that I start sneezing uncontrollably and then bleeding out of both of my nostrils.

I'm sore everywhere and I start to worry that I'm going to get early arthritis. Sounds miserable, right? But the truth is I would rather be there so much more than on campus.

On campus, the stress of needing to sound smart and driven and be good at data analysis is exhausting. I feel so alien here sometimes, and I never really thought of myself as an academic. I definitely never thought I would find myself in a PhD program.

But out in the field, I can forget about all of this.

I'm back at my plot and it's getting late in the day, so I pick up my phone to check the time. I'm surprised to see a missed call from a friend back home. It's not someone who usually calls. Then a voicemail pops up and then I start to see this flood of text messages and more calls. I'm trying to unlock my phone but my hands are so dirty that I can't do it and I'm panicking.

Jasmine Anenberg shares her story at Kitt Recital Hall in Flagstaff, AZ in September 2023. Photo by Joshua Biggs.

Finally, I get my phone open and I see the first text. It reads, "I have some bad news. Adrian overdosed. He's dead."

I start to scream. The sun is coming down on me harshly. I look up at the sun for some sort of answer, but I'm blinded and all the color drains from the landscape. The beautiful birds that I was hearing only moments ago are gone now and they're replaced by the incessant buzzing of mosquitoes.

Let me tell you about Adrian. Adrian and I bonded over grunge rock and getting high behind dumpsters. There wasn't much else to do when you're 14 in the suburbs of San Jose.

All through high school, I would go to his house to watch him paint. I always praised him but I was secretly so jealous of his natural talent. He had this way of seeing these ordinary details and making them beautiful somehow.

Adrian rolled the most perfect joints you've ever seen in your life. He painted portraits of me. He made me feel seen. Sometimes, he would show up to parties and he would dramatically unzip his jacket and open it and a pile of meats would fall out that he had shoplifted from the grocery store, and we would grill them for all of our friends.

Once in our mid 20s, I was too hungover to move from the couch and I watched him make me a single fried egg. I watched as this enormous Filipino man in pinstriped, train conductor overalls and these stupid, hipster, tortoiseshell glasses towering over this tiny onion and sculpting it into perfect slivers. He would throw it into the pan and I started smelling spices I couldn't really pick out.

When he brought the plate out to me, the onions were placed so intentionally and carefully over the egg that it looked like fine art. Eggs aren't special to me. I eat them every day, but this was the best egg I've ever had.

I resent him for dying. He saw the world in a way I thought I never would. His dreams were so much bigger than mine. He had so much to contribute. This could have easily happened to me and, sometimes, I wish that it had, but I chose to abandon home and do this weird science.

Jasmine Anenberg shares her story at Kitt Recital Hall in Flagstaff, AZ in September 2023. Photo by Joshua Biggs.

So, here I am back at my field site at my plot. I'm the only person in this huge field and, once again, I'm hunched over and I'm trying to see these extremely small and dried up, shriveled mosses. My nose is in the dirt and my butt is up in the air and I can't help but laugh at how insane I must look. I must be the only person in history who has ever looked at this one piece of moss. They're such strange and seemingly inconsequential organisms.

And then I remember Adrian and the egg. I realize I wasn't jealous of his talent and his intellect and his technique. It was his ability to see beauty in the mundane. Suddenly, I realize, I see this way too.

Most people walk by these mosses without even noticing them. But, to me, these mosses are like our elders. They're some of the oldest organisms on earth. They're certainly older than most of the plants around us. The fact that they're still alive and haven't gone extinct is a testament to their resilience.

These mosses perform miracles. During drought periods, they can dry down completely and be dormant for months to even years. Then when the rain finally does come, they wake up immediately with this greenness and get right to work. That’s a super power that most plants do not have. I'm realizing now that my attention to these mosses makes them beautiful.

This is the greatest gift anyone has ever given me. Adrian taught me to see the ordinary, to focus on the ordinary, to make it beautiful, and I see it right here in the dirt.

Thank you.