Disgust, often seen as a primal and universal emotion, can reveal a lot about our values, boundaries, and cultural norms. In this week’s episode, both of our storytellers are confronted with something that grosses them out.

Part 1: While on a school trip in Russia, Cassandra Hartblay’s vegetarian dietary restrictions keep getting tested.

Dr. Cassandra Hartblay is an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto, where she works with graduate students in Anthropology, European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies, Disability Studies and Sexual Diversity Studies, as well as undergraduates in Health Humanities. She is author of the 2020 book "I Was Never Alone or Oporniki" (University of Toronto Press 2020) and numerous articles, a documentary play, and co-curator of the #CripRitual art exhibition. If you can't find her, she's probably our running or swimming with her dog, an Aussie-Retriever mix named Arlo.

Part 2: As a meat lover, Jenny Kleeman has high hopes for the world’s first lab-grown chicken nugget.

Jenny Kleeman is a journalist, broadcaster and author. She writes for the Guardian, the Sunday Times and The New Statesman and makes radio and podcasts for the BBC and the Times. Her latest series for BBC Radio 4 and BBC Sounds, The Gift, tells the story of the remarkable truths that emerge when people take at-home DNA tests. On television, Jenny has reported for BBC One's Panorama, Channel 4's Dispatches and VICE News Tonight on HBO, as well as making 13 films from across the globe for Channel 4's Unreported World. Her first book, Sex Robots & Vegan Meat, was published in 2020 and has been translated into ten languages. Her second book The Price of Life, was published in March 2024.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

I was a willful child. When I had the opportunity to play oboe instead of flute, I picked oboe because it's weird and hard. When I learned as a young child that meat comes from animals, I unilaterally became a vegetarian, much to the consternation of my poor working parents who did eat meat.

And when I got to high school and everyone else signed up to take Spanish and French, I took Russian. I wasn't very good at learning Russian. In fact, I had several C's mixed in with my usual A's. But over those four years of high school, I fell in love with the people and the culture and the weird history. And I decided that when I get to university, I was going to be a Russian major.

My first week on campus in undergrad, I sign up for my Russian class and I also find myself in a course called Introduction to Cultural Anthropology. The professor, Dr. Weatherford, is an expert in Mongolia. He's done tons of fieldwork in rural Mongolia and every week he brings out these interesting objects from his own fieldwork to illustrate the points he's trying to make in his lessons.

Cassandra Hartblay shares her story at Burdock Brewery in Toronto, ON in October 2023. Photo by Glenn Pritchard.

One day, he's telling us about how you have to build rapport with the people you're doing ethnography with by accepting their hospitality and building goodwill. He tells us a story about a time when he was sitting in a yurt with one of his hosts and they took a chunk of meat and they bit off the chunk of fat and plopped the chunk of fat into Professor Weatherford's little cup of salted milk tea because, of course, you have to give the best piece of meat to the guests.

Now, Professor Weatherford was like, “Obviously, in our society, that's disgusting, but in this culture, obviously, I was being treated as the guest, so I smiled and thanked them and I ate the piece of fat.”

He goes on to explain the concept of cultural relativism and the idea that when you step into another culture and try to understand it from the insider's point of view, you have to set aside your own ideas of what's good and bad or delicious and disgusting and really just accept the world view of the people you're interviewing or working with.

So, he brings out the next object that's going to illustrate this lesson. He goes to someone sitting down the aisle from me, at the end of the aisle, and he says, “Here's this little vessel, and you can open it up and look inside. What do you think that is?”

The guy kind of looks at it and he has no idea.

He's like, “Well, that's rendered horse fat and it's used as a lip balm. Try some.”

The guy declined, but he did kind of start to pass it down the aisle of the students, as everybody was, as he continued his lecture.

It's coming toward me and it's getting closer and closer, and I'm thinking, “Am I the kind of person who's gonna try the lip balm?”

On the one hand, it's made of horse fat and I'm a staunch vegetarian. But, on the other hand, I like weird hard things and I like getting good grades, but, also, it's been in his office for maybe 10 years and everybody's been sticking their fingers in it.

So, when it gets to me, I kind of examine it and I observe the craftsmanship. I sniff it and I can't put my finger in it. I don't. I close the lid and I pass it on.

By the time I got to sophomore year, I was a double major in Cultural Anthropology and Russian Studies. And what I wanted to do more than anything in the world was go on Study Abroad. I found the perfect program. It was a program in Russia where you could do your own ethnographic field study that could turn into an honors project. Sign me up! What a nerd.

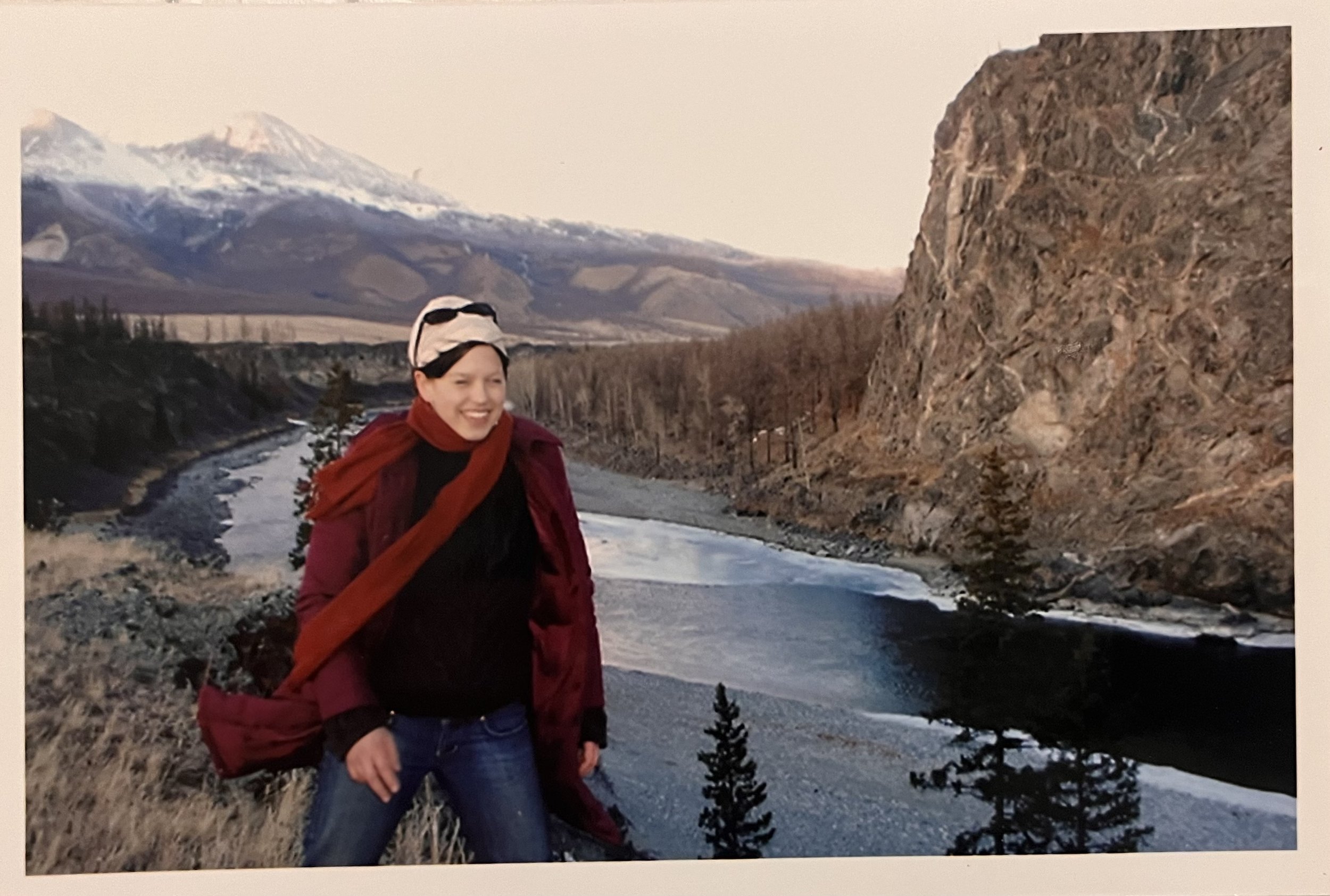

And, no, this wasn't just in Moscow or St. Petersburg, like every other program. No, no. I was going to rural Siberia.

Cassandra Hartblay shares her story at Burdock Brewery in Toronto, ON in October 2023. Photo by Glenn Pritchard.

Fast forward, it's the winter of 2005. I'm in the city of Irkutsk in southern Siberia with ten other American undergraduate students and we are living with host families. Every day we go to the university where we learn Russian language and culture and history.

One of the big things that probably won't surprise you to hear is that in a group of 11 Liberal Arts college students, there were five vegetarians. So, a lot of that chatter in the hallway was us whispering to one another, catching up, “What did you guys have for dinner last night?” “How's your stomach?” And trying to navigate our menu options for dinner in middling Russian with our host families.

My host mother did one time prepare me a beautiful soup and she proudly said, “You know, it's vegetarian. There's no pork or beef.”

I looked over her shoulder at the bubbling pot with the chicken bone on the stove and I smiled and accepted my bowl and said, “Spasibo, vse ochen vkusno.” “Yes, thank you. It's so delicious.” And I did my very best to finish my portion.

Not long after that, we were preparing for one of the big excursions of the Study Abroad program. We were going up into the mountains with our whole group, up high on the plains. So, we took an overnight train and then a bus ride, and we're going to a small village up in the high steppe near the border with Mongolia. I was so excited and the local tourism agents who met us were also really excited to have a group of 11 American young people because they thought it might help attract tourists to the region so they planned us this amazing program.

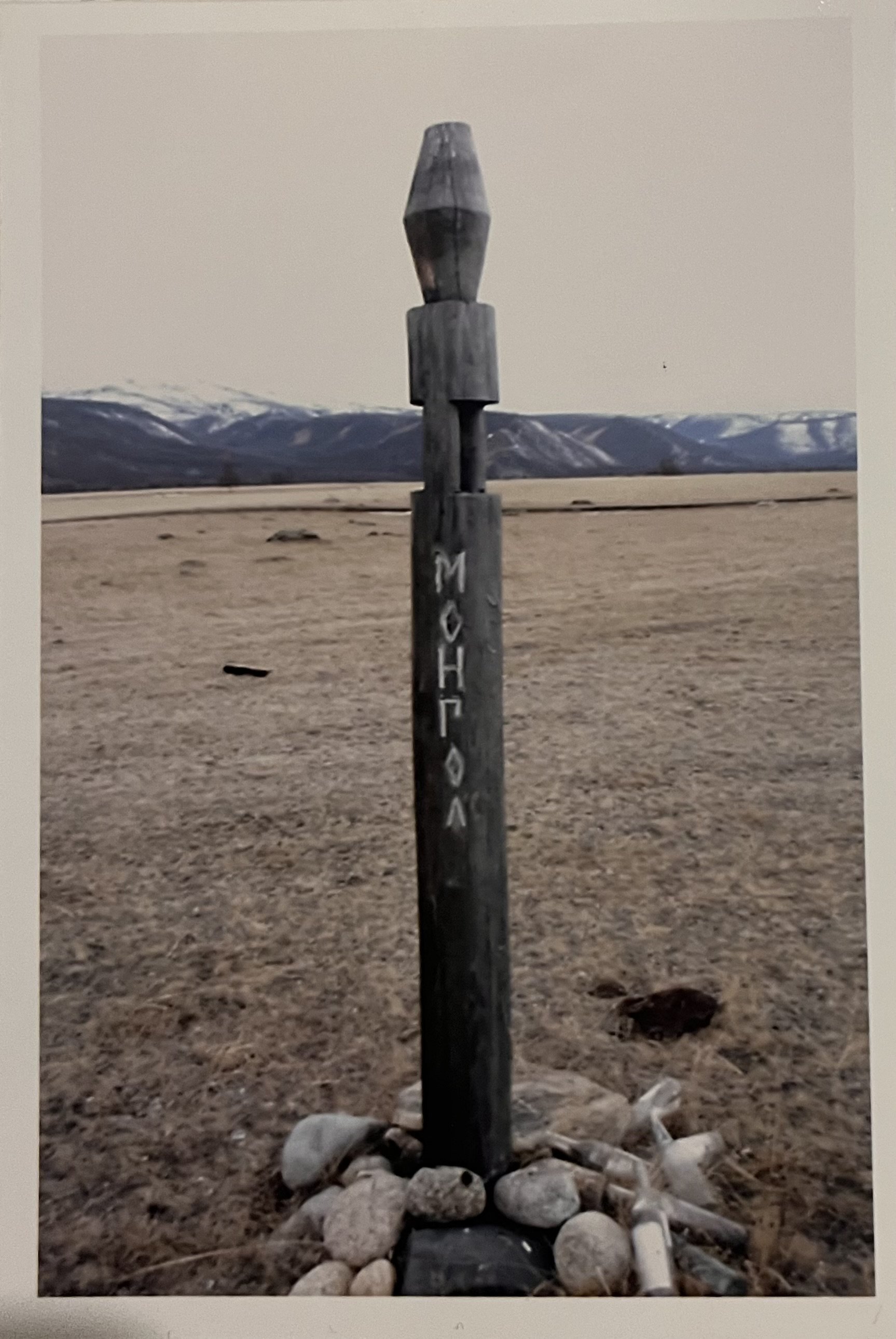

We met the local shaman, we learned a few words of Buryat, which is the name of the local language and ethnic group, and the final day was going to be a big tour of the local sites of the natural environment and a picnic.

We show up in the morning of the picnic and there are two vans waiting for us. There are these big kind of Soviet‑style bread loaf vans. They're white with these giant craggy tires. We kind of split up, half of the students in one mixed in with some locals who are coming on the picnic

So, off we go and the big tires are there for a reason because there are no roads in nomadic steppe regions. You just drive off and over some rocky terrain and through a creek and through a small forest and then off onto the steppe.

Eventually, we come to a place where the steppe kind of comes to a giant cliff and there's a beautiful river below. And there's a little tree, there aren't a lot of trees on the steppe. There's a little tree and it has a bunch of prayer flags hanging on it.

We all get out of the vans and everybody says, “You know, let us tell you about our culture as Buddhist animist nomads when we come to a place where the river spirit meets the land spirit or the forest spirit meets the steppe spirit, we stop and we let go of our baggage and we reflect and we douse ourselves in holy water.” And then he pulled out the bottle of really cheap vodka. Holy water.

So, we all had a shot of vodka and chased it with a pickle and got back in the vans and kept driving.

And I'm already thinking, “This isn't the kind of picnic I was expecting.” Meanwhile, after the first shot, I realized that our driver is 16 years old and he's just gotten his license and we're driving along a cliff face, but he seems like he's got it under control.

A few more stops later and we come to this lava field where there was a very ancient volcano, but there's still volcanic rock on the ground. I'm kind of kneeling down, just checking out, like a little tipsy, the rock with the moss growing on it.

My friend Sienna, who had been riding in the other van, comes up to me and I'm like, “Oh, hey.”

She's got a kind of weird look on her face. And I'm like, “What’s up?” She starts talking in that whisper that lets you know that something intense is about to happen.

She's like, “There's a sheep, a live sheep, in the back of our van tied up. And when we get to the picnic, they're going to slaughter it and we are going to eat it.”

And the wheels are turning in my head and I'm kind of thinking, “Uh, picnic.” Piknik, the words sound the same in Russian, but maybe they don't mean the same thing after all. I was thinking cheese, wine, grapes, live sheep slaughter. Okay.

But she's still talking and what Sienna is telling me is that I have been designated with the task of telling every vegetarian in my van about the live sheep so that we can prepare ourselves and not act disgusted but rather show gratitude for our hosts when we accept this sacrifice.

So we get back in the vans, have a few more shots of holy water. I'm frantically whispering to the people in my group without trying to let the hosting people know what we're talking about. And, eventually, we arrive at the picnic spot, and it's beautiful. There is a nice blanket of yellow soft pine needles on the ground and a beautiful little babbling brook.

They get to work. The locals get to work setting up a campfire and preparing some tea on the fire. Then I see her, the sheep.

She's woolly, white, soft nose, weird square pupils in her kind eyes, and I know that she's about to die. And I realized and all of my classmates realized that now is the moment that we have to decide whether we're going to watch the sheep die or not.

I think to myself and I remember Professor Weatherford's class and I remember the lip balm. I know I want to be an anthropologist and I know I like hard things, and I'm like, “I'm gonna watch.”

So, I stand there and I don't have any disgust on my face. I have pure reverence for the ceremony and the tradition of the people who are going to slaughter the sheep. Maybe I had reverence because I was experiencing it as a funeral. But, anyway, a lot of the meat eaters, strangely, were not watching.

What then happens is the four strongest men each take a limb of the sheep and they hold her kind of splayed out and her chin also exposed. Then she's kind of struggling but she kind of gives in when she realized that she can't fight it. Then it turns out that the tradition is that the youngest man present, our 16‑year‑old driver is going to insert his hand into her open chest cavity while she's still alive and, holding her heart, determine when it stops beating.

I'm watching this happen like a scene from Grey's Anatomy as the other guys explain it to him what he's going to do and he looks really nervous. So, I'm watching him as he holds her heart beating in his hand. He looks really nervous but he slowly starts to get a bit more calm. Then when her heart stops, he gives a nod.

They slice her from her chin to her anus and the women come over with a couple of vessels and a big giant ladle and they start ladling the blood out of the sheep. I'm watching. Then they take the intestines out of the sheep and, let me tell you, sheep intestines are large. There are a lot of intestines. It took a giant bowl that took two women to carry, so I'm like, “Where are those intestines going?”

Cassandra Hartblay shares her story at Burdock Brewery in Toronto, ON in October 2023. Photo by Glenn Pritchard.

I follow the intestines and they keep walking. They're going further and further away with this giant plastic bowl of intestines. Then I see that what they're doing is they're actually going to empty all the excrement out of the intestines, like hand over hand. And there's a pile of sheep poop up to my thigh. It gets kind of grassy at the end, actually. You have digested grass.

But then they start washing the intestines and they clean them and they mix the blood that they have saved with milk and onions that they've chopped and they make blood sausage. They put it in a big vat of water to boil.

And when they are adding the sausage to the pot, I realize that something else is happening. It's actually time to take the first bite of sheep. The first bite of sheep is going to be a slice of raw liver dusted with salt on a slice of Soviet‑style sourdough bread.

So, we all gather in a big circle. I'm holding a plastic cup of holy water aka vodka in one hand and I'm already pretty drunk. I'm holding the slice of bread with raw sheep liver on the other hand and it sort of smells wet and metallic. Then next thing I know, I'm taking a bite of the raw liver and I'm chewing and swallowing and chasing it with vodka. I ate the sheep.

Then I couldn't eat the second bite, so I handed it to my friend standing next to me and beseeched him to take it.

If I'm honest, I don't really remember much of what happened the rest of that adventure day, probably because of the vodka, but I did make it back home, eventually. Now, whenever I think about how I became an anthropologist, I think about that sheep.

Part 2

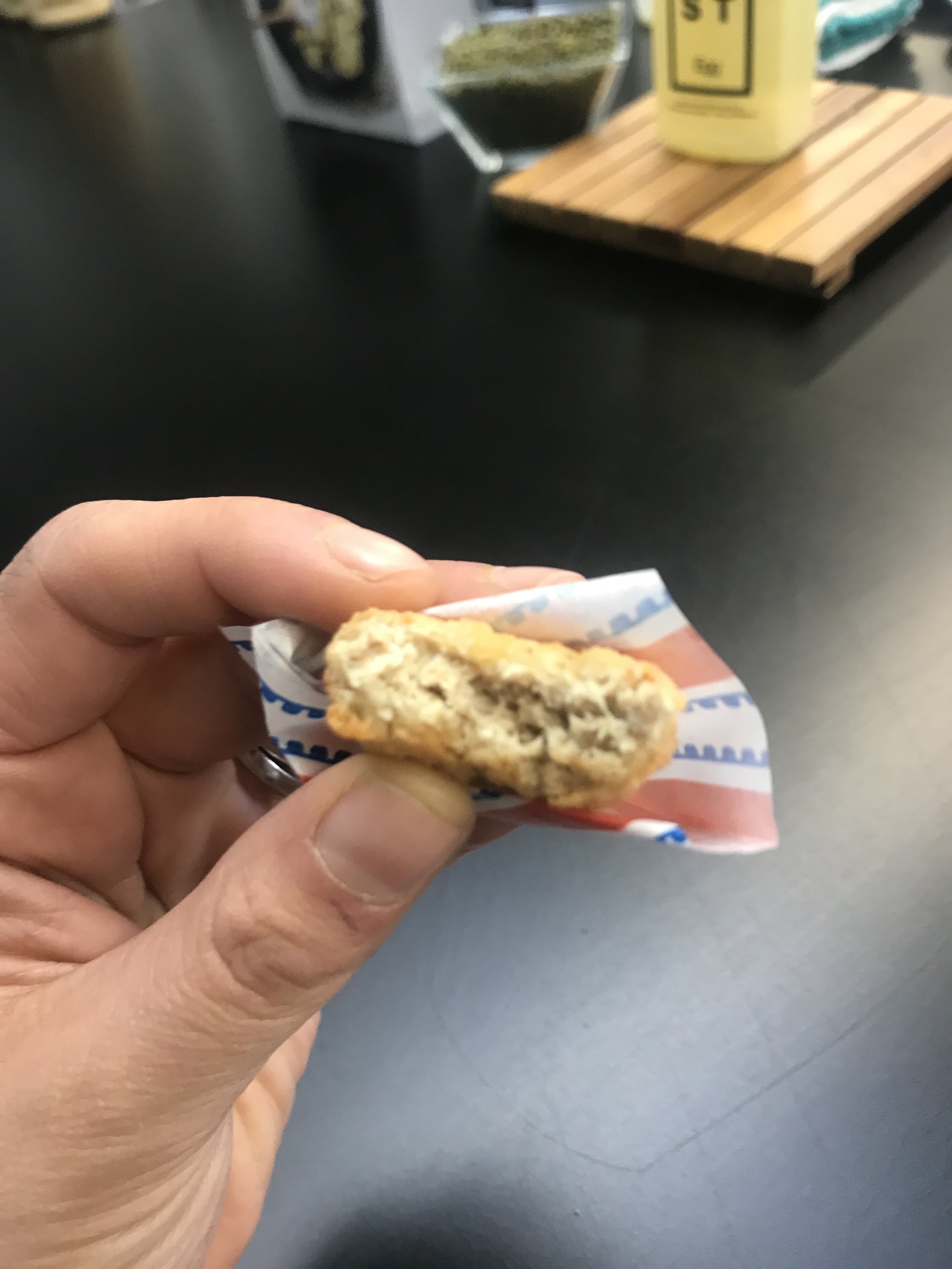

I'm here to tell you about a time pretty much five years ago to the day exactly when I was in a converted chocolate factory in San Francisco, sitting at a counter with lots of people staring at me, holding in my hand the most special chicken nugget in the world. I had flown halfway across the world to have this chicken nugget in my hands. It had taken about 15 or 20 emails to get anywhere near this chicken nugget and it was a priceless chicken nugget or, rather, they wouldn't tell me exactly how much it cost, except it was probably at least $1,000, this chicken nugget.

Not many people in the world had ever got to taste it. This was no ordinary chicken nugget. It was chicken but not chicken as we know it, because the chicken inside this nugget had not been grown on the body of a chicken. It had been grown in a laboratory. I'm going to tell you how you do this here.

You take a biopsy from a live chicken, don't have to kill it. You could give it a little anesthetic first. You get a little sesame seed size bit of their flesh. You isolate the stem cells, you bathe it in a nutrient bath. I realize I'm sounding like a scientist here, but I'm not. I'm a journalist.

And you put it in a bioreactor and it proliferates. One cell becomes two, two cells become four, four become eight, and so on until you've grown enough chicken, enough meat to harvest and cook and eat.

Jenny Kleeman shares her story at Imperial College London in November 2023. Photo by Richard Mukuze.

Back then in 2018, this was pretty radical stuff. Very few people had got to taste it. And this meat was being touted as the savior of planet Earth. I really wanted it to be the savior of planet Earth because I loved meat. I really loved meat.

For me, meat made a meal, and particularly steak, which is the kind of most ethically dubious of all meat. Steak and lamb are both pretty bad, but steak, for me, that was the big thing to have. That was the celebration food. When my husband asked me to marry him, he cooked me a steak afterwards. It's what we might have on my birthday. I do love a steak.

But I know that meat as we know it is completely unjustifiable. The industrialized creation of meat for global consumption is appallingly terrible for the planet, it's terrible for our bodies and it's terrible for animals. 70 billion animals are killed every year because we think they're tasty, not because we need to eat them. We can survive being vegan. If we want to, we can take supplements. We can have a balanced diet without meat. We don't have to eat meat.

So, this tiny little beige thing I was holding in my hand promised me that I could have meat with a clean conscience. I could have my steak and eat it, because, also, you can make any kind of meat out of this stuff as well. You can make kosher bacon. You can make foie gras with a clear conscience, so I was really, really up for it.

And I was surrounded by PR people in this startup and they're all watching me. I'm about to bite into this thing. It's small, because it's very expensive. and I'm there as a journalist knowing that I'm really lucky to have this.

I'm not a food critic and I've been reading on the plane overall about how to be a food critic and what you should think about and the notes that you should take. I realized I was only really going to get like three or four bites out of this little thing, but the time had finally come.

So, I bit into it and it tasted like chicken. I mean, it was chicken. I don't know what I was expecting it to taste like, but it tasted like chicken. It had that unmistakable aroma of chicken. On my tongue, in my nose this was chicken. It was great.

And I smiled. I was so happy. And they said, “What do you think?”

I said, “It tastes like chicken.”

Then I took another bite and I chewed. Gradually, as I chewed, I realized that it was completely disgusting, because whilst it tasted like chicken and it was chicken, there were no discernable pieces of flesh in this chicken nugget. This was not chicken as you know it, as I know it. This was not meat. This was chicken cells in a kind of mush, in a mash bulked out with something and then coated with some kind of batter and deep fried. This was not proper chicken.

And there was some sort of hind part of my brain, this primordial part that I think we've evolved to have as human beings that keeps us alive when you eat something that is like meat but not quite right. Your brain is telling you, “No, you must not swallow this because it is going to poison you. You must spit this out,” but I'm surrounded by all these PR people who have flown across the world and this is a very expensive chicken nugget.

So, I don't spit it out.

I think they must have seen something in my face, because one of them said, “Any other feedback? We take all comments.”

And I said, “It's a bit mushy.”

But, in one respect, the chicken nugget was a great success because it did turn me vegan for a full four days. I could not eat any meat because the memory, the kind of backwash of this horrific mushy, mushy chicken came back into my head.

Anyway, I came home and I started writing the book that I was writing, which is called Sex Robots & Vegan Meat, the vegan meat being the lab grown meat, the nugget.

Writing books is a lonely business. You go out and you do the reporting and then you come home and you're kind of scowling in front of your computer all day. I always look forward to the evenings where my husband would come home and we'd have dinner and I'd talk about what I was writing about.

When I was writing the section of the book, which is about how meat is indefensible as we know it, industrial agriculture, I'd read a lot of scientific papers and was really shocked by the extent of how bad things are and wanted to share it with him.

So, we have a kind of kitchen island where you can cook. He was cooking dinner and I was sitting up at the kitchen island next to him.

I was saying, “You know that industrial agriculture produces more greenhouse gases than every form of transport on the planet combined.”

And he said, “Well, that doesn't mean I should eat less meat.”

And I said, “How can you say that?”

And he said, “Well, carbon capture. They're going to invent something that will suck all that stuff out of the sky. That’s not a reason to eat less meat.”

And I said, “Okay. Well, did you know that like when it comes to antibiotics, you remember when I had tonsillitis and I wouldn't go to the doctor for antibiotics because we're all being told you mustn't get them unless you're dying because of medicine resistant horrible bugs that are learning how to beat the antibiotics that you've really got to ration them well, 80% of all of the antibiotics in the world are given to animals that aren’t even sick. They dose them up so that they can stand in their own shit next to each other, flank by flank, and so we can eat them cheaply.”

And he said, “That's just a problem with government policy, isn't it? It's got nothing to do with meat. They should just stop people giving these antibiotics to animals.”

I couldn't quite believe it. I was like, “Well, what about the fact that meat is a major cause of deforestation? What about pollution of water? Waste of water? Waste of energy? E. coli, Salmonella, pandemics?”

And he just didn't want to hear it at all. In fact, he just said, “I don't want to talk about it,” as he tipped the beef into the casserole dish making his famous chili.

I was sitting there and thinking why my totally rational but very kind of stubborn husband, he's a builder, by the way. He's a very manly, chunky husband. Why he would be taking this all so personally, because he did seem to be taking it personally. We get on very well and he was saying he just didn't want to hear it.

Then I realized it's because meat is actually more than food. Meat is culture, really. For human beings, for many human beings, meat is about our dominance over the animals, our mastery of the world. It's about killing and manliness. I think maybe he was worried that if I was swallowing all these arguments about why it wasn't okay to eat meat, he would have to swallow them too and that would maybe make him a little bit less of a manly man. And he didn't really want to hear it at all, so we didn't talk about it again.

Jenny Kleeman shares her story at Imperial College London in November 2023. Photo by Richard Mukuze.

And here we are, five years later, the chicken nugget that I ate, the mushy nugget was the first lab grown meat ever to go on sale. It went on sale in 2021 in a private members club in Singapore. I think they cost about $50 each, so not exactly saving the world.

The thinking about lab grown meat has also changed too. It's no longer being touted as a savior of the planet. It may be less carbon producing to eat a lab grown beef burger than beef from a cow, but when it comes to chicken the jury is still out. Actually, the best way if you're going to eat meat, the best thing to eat is insects, because it's very good for the planet if you eat insects. If that's what's driving your food choices, you know what to eat.

This year, the FDA in the US approved lab grown meat for the first time. So, very soon, it's going to be all over American shopping markets. You can buy it everywhere, if you want to. I'm sure it must be better than what I ate five years ago. It has to be better. I think it's still quite expensive.

As for me, well, I really don't eat meat very much anymore. I certainly never have it before dinner, will never have any meat at all with my lunch. Certainly, no fry ups for breakfast either. I only eat it a few times a week, because that's the thing. You don't have to be a vegan to save the planet. You can just eat a little bit less and make sure that the meat you eat counts.

And the meat that I eat does count, because they are meals that I share with my very manly husband, who has not changed his diet at all in any way whatsoever.

One thing, though, for me, is completely off the menu for the rest of my life and that's chicken nuggets. I'm never going to eat one of them again.

Thank you.