In science, failure is as important as success. In this week’s episode, our storytellers share times when they failed at science or science failed them.

Part 1: Samuel Scarpino is convinced that the paper he wrote about how hard it is to predict infectious diseases should win a Nobel Prize.

Samuel V. Scarpino, PhD, is the Director of AI + Life Sciences at Northeastern University and a Professor of the Practice in Health and Computer Sciences. He holds appointments in the Institute for Experiential AI and the Network Science, Global Resilience, and Roux Institutes. In recognition for his contributions to complex systems science, he was named an external Professor at the Santa Fe Institute in 2020. Prior to joining Northeastern, Scarpino was the Vice President of Pathogen Surveillance at The Rockefeller Foundation, Chief Strategy Officer at Dharma Platform (a social impact, technology startup), and co-founded a data science initiative called Global.health, which was backed by Google and The Rockefeller Foundation. Scarpino is a regular presence in the news, providing over 500 interviews to outlets such as Good Morning America, The Wall Street Journal, Vice News, The Atlantic, and NPR. He has authored more than 100 academic publications, which has appeared in journals such as Nature, Science, Nature Medicine, PNAS, Clinical Infectious Diseases, and Nature Physics. The New York Times, Wired, the Boston Globe, National Geographic, and numerous other venues have covered his research.

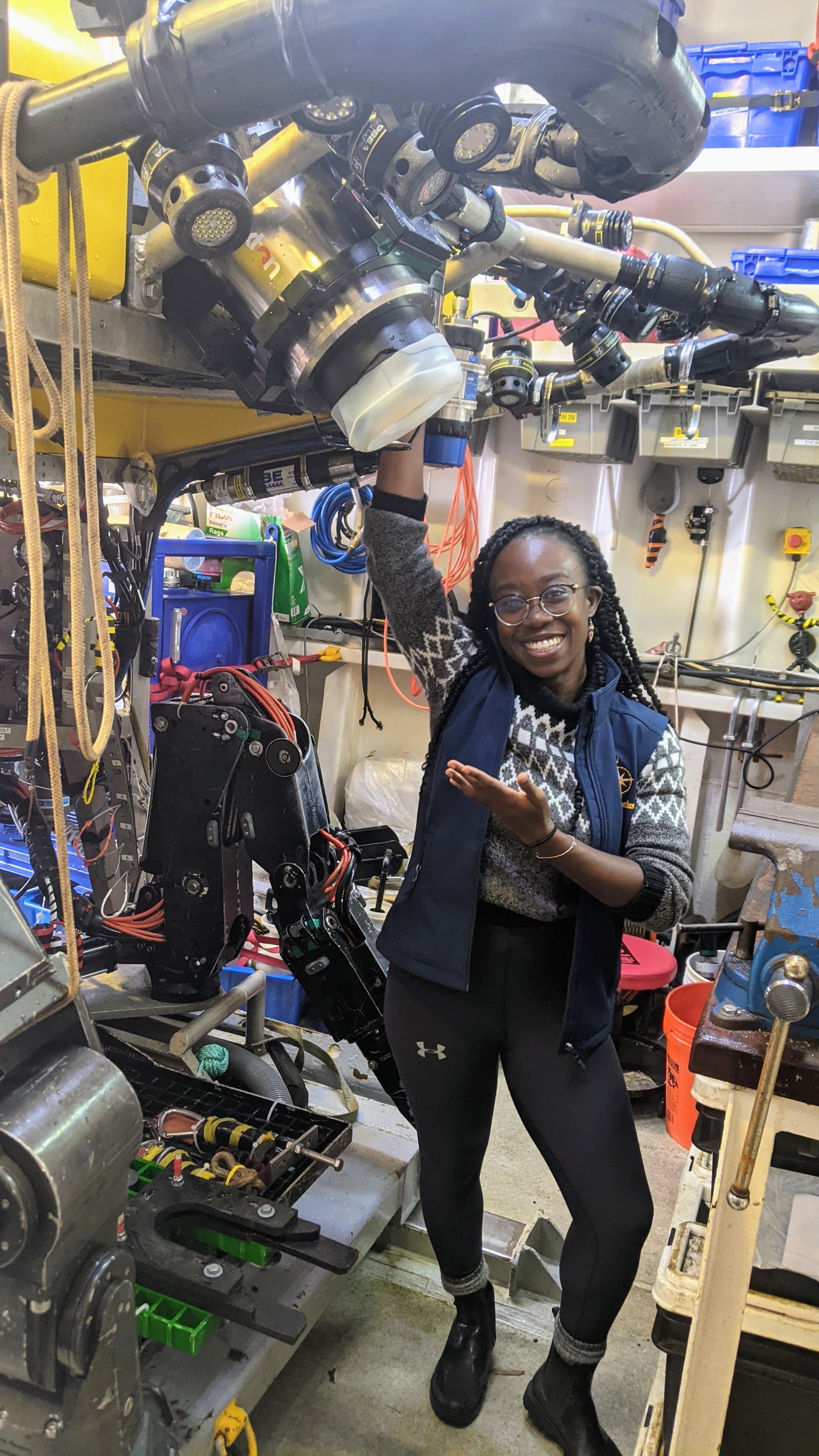

Part 2: It’s grad student Moronke Harris’ turn with the deep-sea robot that no one can find, and she needs to conduct her research..

Moronke Harris (moronkeharris.com) is a deep-sea explorer and oceanographer with experience in climate engineering, blue economy, and intergovernmental (Canada, USA, Russia, Japan, and the Republic of Korea), multi-vessel research expedition planning in the high seas. Currently completing a PhD in Oceanography at the University of Victoria (BC, Canada), her research focuses on the most unexplored areas of the ocean, containing the most potential for discovery. Moronke specializes in the alien world of seafloor superheated geysers: hydrothermal vent ecosystems 1000-4000 m under the ocean's surface. She has spent over 110 days of her life exploring Earth's final frontier. Beyond academic pursuits, she is the founder of ‘The Imaginative Scientist’ (linktr.ee/imaginativesci): a science communication and creative consulting brand blending traditional outreach and artistry to produce an audience-first approach that engages, invites, and inspires curiosity. Brand experience includes 50+ national and international speaking engagements, video production and content creation collaborations garnering 50,000+ views, and consultation for gallery installations, video game development, and film production.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

The first time I found myself in line at Four Corners of the Earth Deli in Burlington, Vermont, I basically had a panic attack. This is actually kind of a good thing, because one of the ways I know I've landed in the right restaurant is if that kind of fight or flight response kicks in. Like, you really have no idea what's going on, but you're pretty sure that it's going to be awesome.

Samuel Scarpino shares his story at MIT Museum in Boston, MA in September 2023. Photo by Kate Flock.

I'm staring up at this wall of placards with sandwich names like Jamaican Avocado, Bohemian Bacon, Babylonian Beef. There's no menu. There's no description at all of what is contained between any of these slices of bread.

And my brain does what it often does in these situations, which is to abandon me and to, instead of thinking through what the plan is going to be when I come to the front of the line, it starts thinking about the science that I'm working on.

At the time, I'd been writing this paper about how hard it is to forecast infectious diseases. Back when I was writing the paper in 2018, I probably would have had to explain a little of why it's so hard, but that kind of goes without saying now.

It turns out it's actually a little bit interesting, right? We were probably all watching the weather with the hurricane that was coming up today and then we had to wait until Wednesday to know whether it was going to come into Boston and this event was going to happen. It's a little bit different in terms of what makes it hard for us to know how many COVID cases there are going to be in six, 10, 12 weeks from now.

But for me, the reason I was working on this paper was because I was bad at infectious disease forecasting. I'd been bad at it for 10 years all the way through graduate school. My assumption had been that I was bad at it not because infectious disease forecasting was hard, but because I was trained as a field biologist. I hadn't taken the right physics classes, the right math classes, the right computer science classes. Like it was something about me that was making this hard.

I get to the front of the line. I'm still thinking about the paper. I'm still thinking about what the conclusions are, which is that it actually isn't me. It turns out that it's just hard to forecast infectious diseases. It's like amazing discovery as someone who's insecure about their own ability as a mathematician and computational scientist realizes it's not me, it's everybody else, like they're the problem.

Samuel Scarpino shares his story at MIT Museum in Boston, MA in September 2023. Photo by Kate Flock.

I get to the front of the line. I order the Jamaican avocado. Latszo, the guy who runs the shop and makes the sandwiches asked if I want pork shoulder. I just say, “Yes. Cheese, of course.”

I get this sandwich and I want you to close your eyes and imagine what's going on here. So he's only got two small panini presses. The shop is half the size of this room. He puts everything together in a very particular way. He's layering three or four avocados on top of mayonnaise with cheese and grilled onions and the pork shoulder and about this much basil. Everything gets grilled down on the sandwich. There's some spice blends that get mixed on the top of it.

I sit down, I eat the sandwich, I have something akin to a religious experience. I leave without ever noticing that on the wall behind me is this giant caricature of Vladimir Putin suckling from a shark next to an even bigger picture of Ivanka Trump. This is how overwhelmed I am emotionally that I don't even realize what kind of place I'm in.

Over the next few months, I spent more time eating sandwiches in Latszo’s shop than I care to admit. And while I was there, I had this idea. Maybe the way that I could finish this paper was to call my friend Giovanni, who was writing with me, convince him to fly over from Italy and we're just going to spend a day in the sandwich shop. We're going to write the thing and it's going to be done.

So, he does this. That's why we're friends. He gets on a plane, he flies over from Italy, Burlington, Vermont. We go into Latszo’s shop.

We tell him, “All right, we're gonna be here for eight hours. We're gonna finish this paper. We want you to feed us. And the good thing is if you don't charge us, we can thank you in the paper as a scientific contribution.” He buys it.

We sit there and this like wave after wave of sandwich is crashing over us, right? So, the Babylonian Beef, he ages his own beef in Tupperwares for two months before he grills it to medium rare on the panini press, layers it into his sandwich. You take a bite of this thing and it's all the flavors: sweet, salty, umami, fat. Every single piece of lettuce is chopped in such a way that it holds the whole interior of the sandwich together. It's not going to break apart in your hands. This guy should have Michelin stars for what he's doing with these panini presses.

We finished this kind of sandwich induced fugue state of writing with a paper that we're convinced is Nobel Prize winning quality. What we have shown is that forecasting infectious diseases is provably hard. It does not matter how many physics classes you've taken. It does not matter what your background is. This is just not something that is doable beyond a relatively short time horizon.

We go home. We get back to my house. We burst through the door. My partner, Laura, is there to meet us. We're babbling on about sandwiches and Nobel Prizes. We're hugging. We're probably crying.

We sit down in front of the computer and we write off a few emails, a whole bunch of our mentors. “We have made a discovery that's gonna change the face of biology. You can read about it in 48 hours. It's gonna be online.”

Sam and his friend giving Latszo a signed copy of their paper. Photo courtesy of Samuel Scarpino.

We fall asleep. We wake up the next morning to a dissertation length email from a mentor of ours that we absolutely revere. The email goes something like this, “You have probably made a major discovery, but the way you have framed it is so unproductive and incompatible with what's in the paper that no one is going to appreciate the work that you've done.”

I don't know if you've seen the episode of The Simpsons where Homer gets this fatal diagnosis in Dr. Hibbert's office and he goes through all the stages of grief in like 30 seconds. That was us after we got this email. We kind of landed on embarrassment and indignation. We kind of flipped back and forth between the two of those pretty quickly.

And instead of doing the appropriate thing, which was to try to process all this, internalize it, understand what's going on, we just said, "Okay, look, we're gonna take the advice. We're gonna rewrite the paper and we're gonna submit it."

That's what we did. We sat down. We changed the paper. We talked about how— and this is actually more accurate that we can tell. We know how many COVID cases there are going to be in two weeks. That's definitely something we can forecast. We know how many flu cases. You've probably seen from the CDC like what the risk is for the fall. It's like next year that is going to be hard to forecast. In eight weeks, in 12 weeks. That's the thing that we were showing. There's some horizon beyond which you can't see.

The paper gets published. We definitely acknowledged Latszo and his free sandwiches in the paper. We actually had to talk with the editor about it, like, "No, no, he contributed resources to the science. We can mention Four Corners of the Earth Deli in the paper."

Samuel Scarpino shares his story at MIT Museum in Boston, MA in September 2023. Photo by Kate Flock.

We had a framed copy that we brought to his restaurant. We made it to the Instagram page. We did not make it to the wall with Ivanka Trump and Vladimir Putin. In fact, maybe I'm kind of glad that it hadn’t happened.

We're on our way out the door. He serves us this sandwich that he was calling ‘The Giovanni,’ which was grilled tortellini with onions and cheese, some kind of red sauce on top of it, fresh jalapenos. I think it was just trolling Giovanni, who's Italian, to see if he would rise to the occasion.

A few years later, we're back in his shop and we don't know where the paper is anymore. I think it's still there, but we didn't have the nerve to ask him and find out maybe he'd thrown it away. But we were talking to each other and we finally had the time to process all this and to process this idea that our own insecurity, our own fight or flight response got the better of us as we were writing this paper, and really did almost derail the entire project.

In the end, we did what great sandwich artists like Latszo do and what great scientists do, which is not try to be the lone genius, but to listen to feedback, be a part of our community and put out something that maybe will change the world, or at least get you some free sandwiches.

Thank you.

Part 2

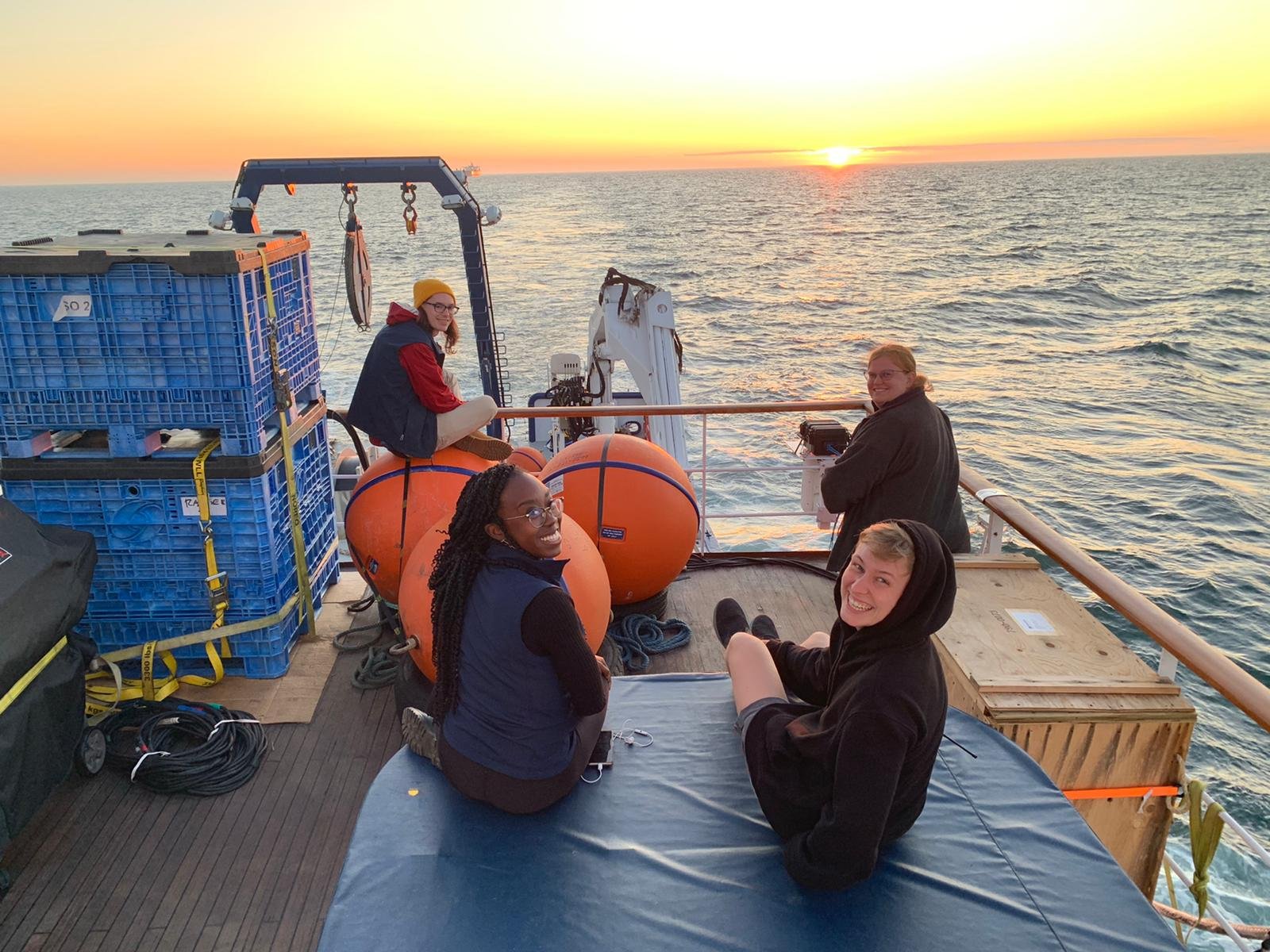

So, there I am standing on a shipyard dock surrounded by the buzz of machines. For the next 28 days, my home will be the 70 meter vessel that spans in front of me. To say I'm excited is an understatement. To say I'm over the moon also doesn't quite hit the mark. To put it simply and least flowery, of course, I'm a scientist after all, I have transcended my human form and I'm now a celestial body traveling on an erythral plane.

Time and space outside of this ship, outside of this dock, have absolutely no meaning to me. Nothing else has ever mattered. All that matters is the vessel.

Moronke Harris shares her story at Fox Cabaret in Vancouver, BC in February, 2023. Photo by Rob Shaer.

The reason for that is because I have waited over four years to be a part of this deep sea research vessel and to work with this particular deep sea expedition company. I have waited for over 10 to go out to sea as a scientist in general.

So, this moment is my golden star. It is my debutant ball. It is everything I have worked for over the past decade coming to life.

I was supposed to get on the ship in 2020, but we all know what happened in 2020. This time around, I was taking absolutely no chances. I had avoided my own family like the plague for over two weeks before getting on the vessel and tested myself almost daily. Nothing is going to mess this up. Nothing is going to ruin this for me. I have taken every single precaution I could probably ever take. This is my time to shine.

But don't allow my air of confidence to fool you because I'm nervous big time and extremely intimidated. Looking around the buzzing shipyard dock, everybody seems to know exactly where they're going and what they're doing.

I'm also the youngest person there. Even though I'm a grad student conducting my own research, I'm also an intern, surrounded by a sea of senior scientists and crew working in what seems like perfect harmony. Man, these guys really know what they're doing. Do I look like I know what I'm doing?

That guy over there, he knows what he's doing, so I'm just going to follow his lead. I power pose awkwardly, looking up at him and back down at myself to make sure I've got it just right. I'm just one inch off there. That's right.

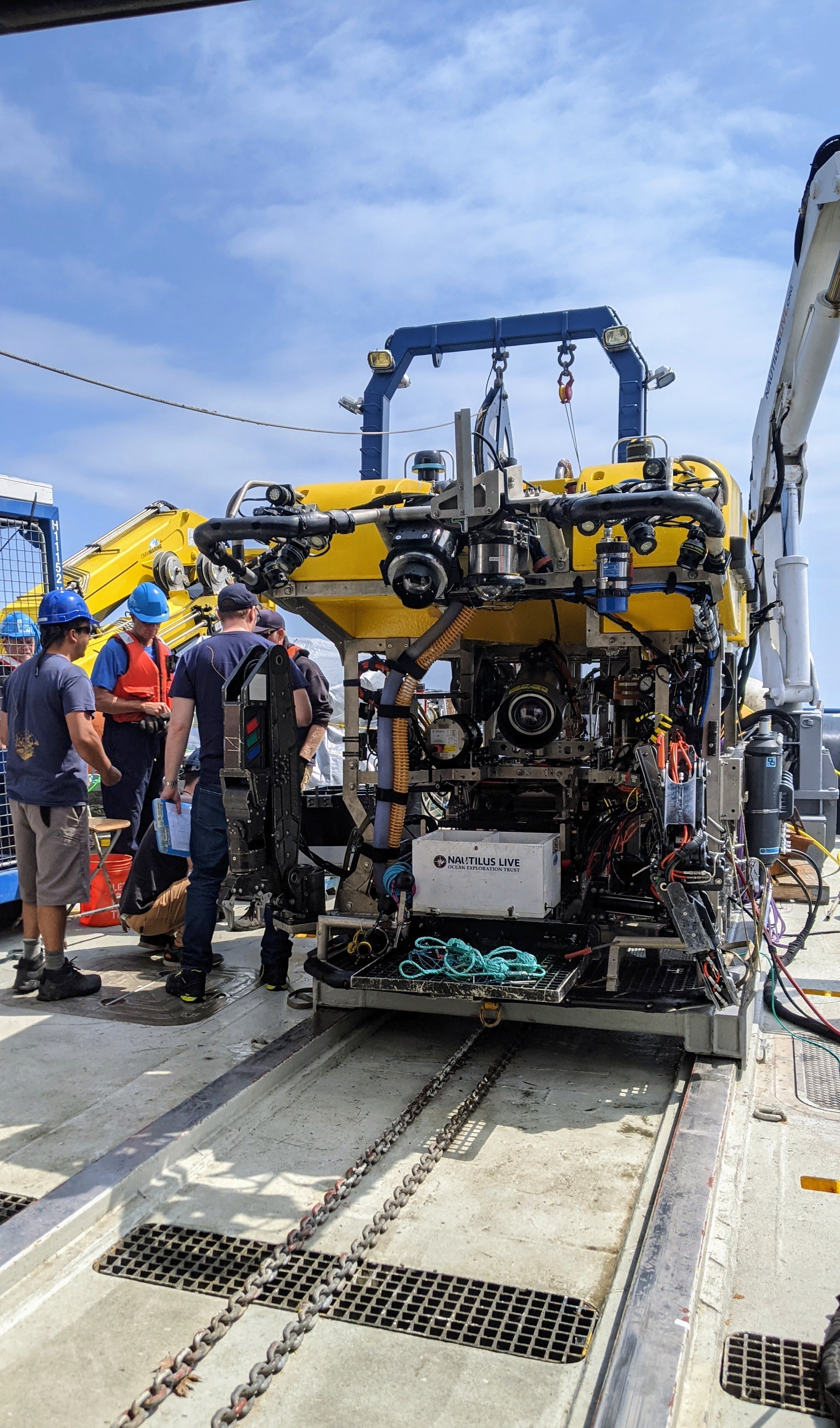

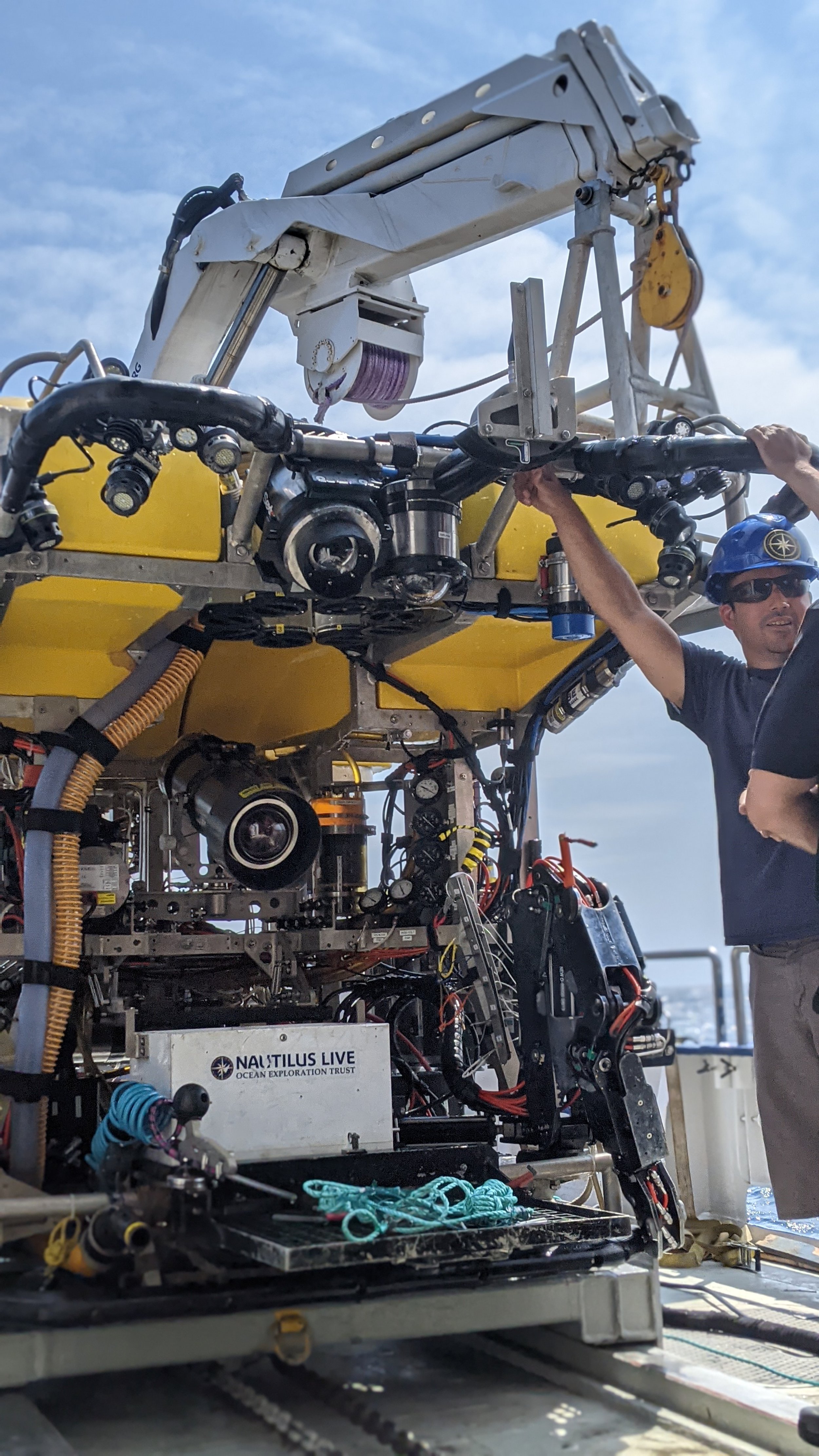

On the bow of the ship sits my most critical teammate, the robot submersible that I'll be using to conduct my research. This is about the size of a Volkswagen Beetle, if a Volkswagen Beetle was six feet tall. This robot is 1,600 pounds, an absolute beast of a machine, equipped with huge manipulator arms, HD cameras and designed to carry up to 250 pounds of samples and tools from the seafloor up to the surface. This is a hefty feat of engineering with a matching hefty price to boot, $4 million, and its every move is going to be streamed worldwide live. No pressure, right?

My biggest challenge will be to implement the dive plan that I've designed for this robot to go to the seafloor 2,000 meters down and collect my samples from hydrothermal vents, which are basically like seafloor superheated geysers.

Have I forgotten anything? No, my perfectionism wouldn't let me, of course. But if I have, it's also way too late, so I might as well not worry about that.

Moronke Harris shares her story at Fox Cabaret in Vancouver, BC in February, 2023. Photo by Rob Shaer.

As I cross the gangway and place my foot on the gangway to start my new journey as a seafaring oceanographer, I hear my mother's voice in the back of my head. “Moronke, 260 nautical miles out at sea with strangers, no land in sight. Are you trying to kill me?”

But I quickly wave that away. She's always been a particularly worried mother because I've always been a particularly adventurous child. But if scuba diving shipwrecks didn't kill her, cliff jumping didn't kill her, backpacking over mountains didn't kill her, and some questionable moves in my dating history didn't kill her, then what was one more notch really going to do? They live long on her side of the family, anyways. She'll be just fine.

On board the vessel, the tone is quickly set during our first all hands on deck meeting. The words of the chief scientist, a tall, intimidating man, ring in my ears. “Time is money. Every minute that we're not meeting objectives, we're losing $100.”

This is a 24/7 operation, which means that the robot is diving 24/7, and all of the scientists work together in two shifts a day. Two four hour shifts to keep the entire operation running at full speed.

I have the four to eight shift, which means that every day between the hours of four to eight, AM and PM, there I sit in the control room, a dark, cold room where the magic happens. It's filled with lit up buttons and switches and humming screens displaying the robot's vitals and multiple views from those HD cameras as it dives.

Although the control room is filled with other scientists chatting through the airwaves coming through our headsets, I am so wrought with anxiety and anticipation that I cannot see past myself, that robot and the stress tethering us together.

Every day I wait my turn. There's no actual schedule that'll tell me when my dive is scheduled to happen, so every day as I open my eyes in the top bunk of my cramped four man cabin and make a mad dash for the sea sickness pills, the pressure sets in almost synchronized with the sea sickness.

“Is today my day? Oh, the chief scientist is really not in a good mood today. I'll let somebody else deal with that. I hope today is not my day.”

For 20 days, I wait in this state of agony just clawing at go time. In one particular day, I make my way down to the lounge to wait for 3:00 PM pastry time The fun thing about deep sea research vessels is that there's no shortage of funding, so there's pastries aplenty, my friends.

And the lounge, being the most comfortable area of the ship, outfitted with screens displaying the progress of the current dive in progress for scientists who are off duty to watch as they feel, was the best place to wait for pastries.

As I'm sitting there in that empty room, sweet smells filling my nostrils, I'm going through the usual motions of my normal self torture. If I mess this up, I'm ruined. They'll never let me on another ship again This is a now or never moment.

I am an extremely relaxed person, as you can probably tell.

As I sit there watching the progress of the current dive, something peculiar happens. The feed cuts to black, my colleagues’ voices on the airwaves go silent and the feed cuts to that classic striped combination.

That's odd. Did somebody hit the off switch? I didn't know that there was an off switch that's that easily accessible. Seems kind of like a design flaw, but, okay. It's not coming back on, but I'm going to stay calm. It's not like I've been waiting 20 days for this moment or anything. Everything's okay.

Oh, my God, it's still not coming back on. Everything is fine. You cannot lose a robot that size.

Shortly after, the chief scientist comes flying through the back door and makes a beeline straight for his sleeping cabin in a quiet rage while I try my best to melt into the floor and stay out of his way.

Colleagues, slowly from the current dive, file into the lounge area, each one looking more forlorn than the next. The air is so tense. The kind of tension that makes you feel you would end up on the wrong side of the boat if you even breathe too loudly.

So, just how do you lose a robot the size of a Volkswagen Beetle? It becomes detached from the ship.

And how does it become detached from the ship? The tether connecting it to the ship, supplying our video feed that's being broadcasted worldwide, breaks.

And how does that tether break? We're not sure, but it sure did.

And what we do know is that, as we're sitting there at sea level on the vessel, my critical teammate is sitting 2,000 meters below us on the sea floor. The only chance of me getting my samples, on the sea floor. All of my hopes and dreams, on the sea floor.

As I'm trying my best to blend into the walls and stay quiet, a braver soul takes a risk as an innocent scientist who, having missed all of the action, makes their way into the lounge from the sleeping area.

“When's the sub’s dive supposed to end,” the confused prey asks, eyes searching around the room, begging for a lifeline.

Seconds that feel like hours pass before that lifeline is cheekily thrown. “Looks like never, mate.”

That one moment, that one perspective shift is all it takes to break the spell. The entire room erupts with laughter and waves of relief wash over everyone's faces. Also, strategies begin to form.

Moronke Harris shares her story at Fox Cabaret in Vancouver, BC in February, 2023. Photo by Rob Shaer.

And although I personally can't hold my laughter, I, for one, am shocked and pleasantly surprised, because here are all these scientists, these academically driven individuals, stereotyped as rigid, behaving like humans.

And I am a scientist who is also human, to the best of my knowledge. Why did I not expect them to be like me? Why did I spend all of this time agonizing and being so hard on myself? Talk about a paradigm shift and talk about a self confidence boost.

So, it's extremely admirable to witness how we all moved from this moment of utter hopelessness and tension to, “Wait, we can fix this and we can do it if we work together.” All it took was that one moment of positivity, because nothing bonds like shared trauma.

Thank you.