Not to get too emo and Simple Plan lyrics on you, but have you ever felt out of place? Like somehow you just don't belong and no one understands you? Well, you’re not alone. In this week’s episode, both our storytellers share stories of a time when they felt like the odd person out in science and in life.

Part 1: Kevin Allison’s ADHD diagnosis sheds new light on why he always feels like he’s left out of the loop.

Kevin Allison is the creator and host of the live show and podcast RISK!, where people tell true stories they never thought they'd dare to share in public, since 2009, and the editor of the book RISK!, published by Hachette. He is also the founder of The Story Studio, a school for storytelling for performance, for business, and for personal growth. Kevin is a member of the legendary sketch comedy troupe, The State, known for their hit series on MTV, and has also appeared on Cobra Kai, High Maintenance, Comedy Bang Bang, Flight of the Conchords, Viva Variety! and in the movies Reno 911! Miami, The Ten, and Wedding Daze.

Part 2: Diana Li feels isolated while studying squid in Mexico.

Diana Li is a science communicator and educator. Inspired by a t-shirt with a squid on it that she bought at a Shins concert in 11th grade, she went on to get her PhD from Stanford University where she studied the neurophysiology and biomechanics of how squid swim. As much as she loves cephalopods, Diana realized what she enjoyed most was helping others pursue opportunities in science and research. She now works at Columbia University’s Mortimer B. Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute in New York City. There, she leads public engagement programs that share neuroscience with the local community, including research internships for high-school students and professional development for teachers across NYC. A skilled science communicator, Diana has spoken on Science Friday, performed at Caveat, and brought her research to local classrooms, aquariums, museums, and science expos since 2015. Her deep dark secret is that none of her hobbies are science related. She’s found making music and art, rock climbing, and enjoying Asian American culture to be the perfect complement to her sciencey side.

Episode Transcript

Part 1

All right. Let's see. It was a Tuesday afternoon in 2019 and I was trying to focus on the emails that were coming in to my podcast. I click on one and it said, “Hey, Kev, long time listener. I love that story you told this week about how your brain works, but, dude, do you not know you have ADHD?”

I laughed, but then my attention was suddenly pulled to my phone and I decided to text my friend Smith who I had known for 30 years. I said, “This is so funny, Smith. This guy just wrote to me and he said, ‘Don't you know you have ADHD?’”

And my friend Smith wrote back, “Kevin, you don't know that?”

So I went to a shrink. Dr. Adler had me fill out this epic questionnaire and then he sat down with me and he said, “Hmm, it says here you have four siblings. You have any nicknames from them when you were a kid?”

And I said, “Yeah. Space Cadet and Spaz.”

And he said, “Well there's your two archetypes.”

Kevin Allison shares his story at the Caveat in New York, NY in July 2022. Photo by Zhen Qin.

I laughed, he didn't.

He said, “Listen, you don't know how your lack of understanding of ADHD has affected you yet, but the more you learn, the more you'll know. And you'll learn how other people's lack of understanding of ADHD has affected you.”

So I went right to a bookstore. ‘Driven to distraction’, ‘Smart but scattered’, and, my favorite, ‘You mean I'm not stupid and crazy?’

What I learned is that people with ADHD do not have a deficit of attention. We have laser focus. It's just we can't aim it at shit we're not interested in. We can become really invested in stuff that really gets to us and really just cannot focus on stuff we don't like.

So I started going through some of my old journals to look at my childhood. I came on one and just saw four words scrawled in it. It said, “Soccer practice. Cold day.” And I thought, “Oh, God, yeah. That day.”

In 1980, I was 10 years old. And in Cincinnati, Ohio somehow, back then, there just weren't things like glee clubs. Elementary schools didn't have anything like musical theater programs. Kids could be interested in sports, sports or sports.

I wasn't interested in sports but I was laser focused on theater. I would go to the library and get all the original cast albums. And then when I had done listening through them, I'd go take a bus to the next library.

One day, I'm locked down in the basement and I'm Sweeney Todd. I'm playing the stereo and I'm swinging an imaginary razor blade through the air. I'm just filled with all this righteous rage, letting all that drama out. Singing, “They all deserve to die.”

I turn around and there's my older brother Peter. And he's looking at me with this look I know so well, like I'm a complete and total freak.

I ripped the needle off the record and said, “What?”

He said, “Wow, a real Hamlet here.” And then he ran upstairs and started yelling to my brothers and sisters, “Hamlet’s downstairs.”

Now, was I thinking, “Gee, how astute. Hamlet was too sensitive for executive functioning in a competitive world.” No. I knew what he meant. he meant I'm a drama queen.

So I hit the floor and I said, “Kevin, don't cry. Don't cry. Don't cry. Goddammit. I've got to find a way not to be so much me. I've got to try to be more like other boys.”

So I sent the records back to the library and I signed up that week for sports, specifically the fifth grade soccer team. Now, it wasn't just the competitiveness of sports that was nerve‑racking for me. It was just that I couldn't keep my eye on the ball, you know. I'd be out there watching the sunset and singing The Ladies Who Lunch to myself, and the other guys were always yelling at me, “Allison, get your head in the game.” That's because our coach Mr. Becker was always screaming at me, “Allison, get your head in the game.”

Kevin Allison shares his story at the Caveat in New York, NY in July 2022. Photo by Zhen Qin.

Now, Mr. Becker, this guy was a real bully. I had joined to get away from bullying but this guy was just always making fun of some kid. Like, “Look at this little fruitcake,” and, “Oh, did you wet your panties, little girl?”

His son Mike was the smallest, weakest little kid on the team and I always felt so bad for him to have a dad like that.

Well, one day, he just launched into a screaming fit. He pulled this one kid aside who had a long‑sleeve shirt on and he said, “How many times have I told you, boys, never, ever should anyone be wearing anything to any soccer practice other than your short‑sleeve shirt, your St. Kate shorts, your tube socks, your cleats and your shin guards. If I ever see anyone wearing any other article of clothing between now and the end of the season, you're off the team. No exceptions.”

And he kept repeating it over and over, the five things we were allowed to wear to practice and nothing else. Then he stormed off. I was like, “My, God, Mr. Becker's insane.”

Well, a week passed and it was time for practice again, but there was a cold snap that day, and a really, really bitter cold snap. Now, I loved when practice was canceled so I was waiting by the phone but no one called. And I'm thinking, “Wait a minute. We're going to have practice today. In this cold? And we have to wear that goddamn dress code he went over and over and over and over with us last week?”

Kevin Allison in his soccer uniform. Photo courtesy of Kevin Allison.

So I put on my cleats, my shin guards, my tube socks, my St. Kate shorts and my short‑sleeve shirt and I went out into the cold. It was a six‑block walk to practice and most of it was uphill, and man, oh man, there were tears coming down my cheeks and freezing in the process. By the time I get to the field, I can see a little huddle there and I'm like, there they are in their long johns and their sweatpants. Some of them even had hats and gloves.

As I'm approaching, I know that most of them could see I'd been crying. Well, Mr. Becker, his jaw dropped and there was that look again, looking at me like I'm a total freak.

He said, “Allison, what could you possibly have been thinking showing up to practice today dressed like that?”

I said, “Because at the last practice you said that under no circumstances were there any excuses ever for ever showing up in anything but this.”

And he said, “Yeah, but did you happen to notice? Today it's cold.” And everyone burst out laughing at me.

And he said, “Why don't you go home, my very interesting little friend.”

Well, a couple weeks ago I saw a thread on Twitter and had a eureka moment where I finally felt like I understood what had happened that day.

This was an ADHD coach and she was explaining that there's a part of the brain called the anterior cingulate cortex that suppresses most of the brain's natural reactions to things in most people. But for people with ADHD, the anterior cingulate cortex is just shut off in that way, so we just have lots and lots and lots of natural pure brain reactions to things without any filtering.

So when someone with ADHD is really interested in something, they can be a little over dramatic about it. And when they're not interested in something. It can be like torture.

She then went on to say this, and this was the eureka moment for me. She said, “There are very real consequences for behaving in ways that the majority find different. They won't tell you. They'll just exclude you. And this creeping sense of exclusion haunts most people with ADHD. In other words, they'll laugh at you for being out of the loop after they left you out of the loop.”

So that's what happened that day. I thought back on it and I thought, “Oh, my gosh. Surely, there were phone calls that went around.

Mike, little Mike the coach's son, he was always so worried about being so little and the weakest player that he was always trying to act tough and cool and he was always trying to get in with the biggest jocks on the team, so he was always on the phone with them giving them the behind‑the‑scenes scoop of what was really going on the team. So surely, he called some guys and they called their buddies to say, “Hey, you know that huge speech about we absolutely can't wear anything but these five things, I mean, come on. Not today.” I was just out of the loop.

So I hope that understanding ADHD is helping me cope a little bit more and I hope that sharing about it I can help other people understand it a little bit better too. But, I will say, it's not like I have no impulse control. I have successfully suppressed some crucial information just to get along in this world at various points in my life.

For example, Mr. Becker, if you're listening, a few years later in high school, I slept with your son.

Thank you.

Part 2

I'm here to say that there is a question that I dread most. “Where are you from?” Thank you for that pall on the audience.

I have a really rehearsed answer by now. I say, “Ehh, Virginia, but I was born in New Jersey,” wink, wink, as you now just found out.

And that often gets interrupted with, “No, no. But where are you from from?”

Diana Li shares her story at Caveat in New York City in August 2022. Photo by Zhen Qin.

Yes, for a while in my life, I did push my Asian-ness to the side. I perfected my English at the expense of my Chinese all in an attempt to camouflage into a white American society, because I figured if I didn’t focus on my race, no one else would. And that would open up room for people to appreciate me for my other, what I felt were more important qualities and interests.

Diana is very sarcastic. She's funny. She's smart. She plays cello great. And, for some strange reason, she's really, really, really into squids.

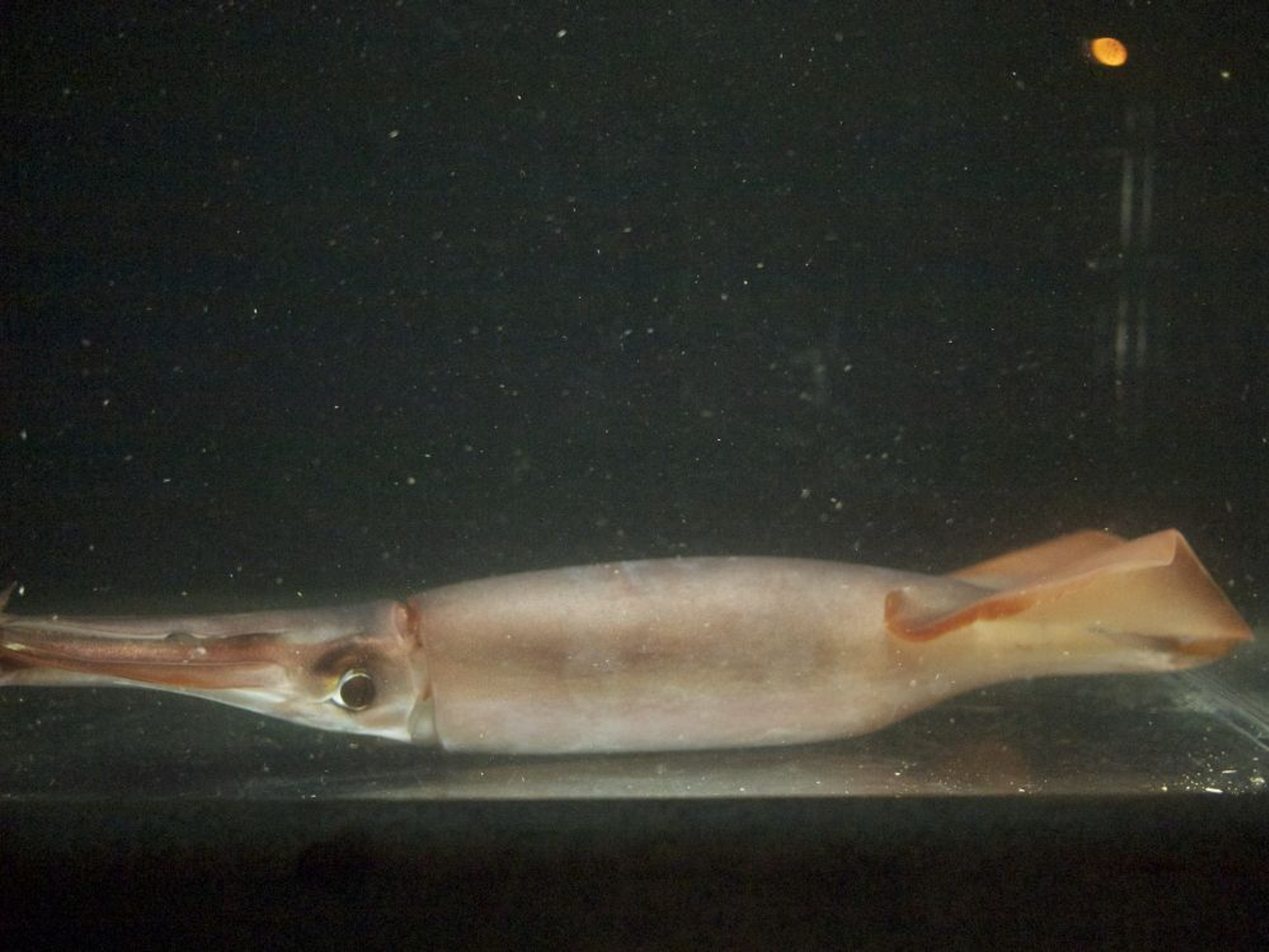

Humboldt squid caught in Santa Rosalia. Photo by Patrick Daniel.

And I can’t tell you why I like squids so much. I think they're so cool even after an entire PhD on the topic. And the moment in college when I learned that I could go to a thing called graduate school where someone would pay me money just to learn about squids, I was sold.

So I went and found a lab. Joined them, got into a program, and that took me for the next three of my six summers to a small industrial fishing town in Mexico called Santa Rosalia.

Now, I had no clue what to expect going to Santa Rosalia. I only need two things. The first thing was, well, if you want to study squids, you have to go to where they are. And one of the species that this lab studied was the Humboldt squid, which is usually found really far out in the ocean, usually quite deep as well.

But Santa Rosalia was a special place because, there, the squids were found really close to shore. It's like a marine biologist’s dream come true.

The other thing I knew, because I'm very smart, is Santa Rosalia is in Mexico. And in Mexico, the language is Spanish. And Spanish is something I had never learned before, so I was very nervous. Maybe you can tell, maybe you can’t tell, I'm an introvert and the idea of not being able to privately practice a language in the classroom and learn all the grammar before going out in the real world made me even more nervous.

And to be surrounded by strangers in a foreign country, I was very nervous. And I had to meet all of my lab mates all at once in the field for the first time, I was so nervous I could have pooped my pants nervous.

But I held it together and made it past the three flights and one truck ride and another like weapons and drugs checkpoint and got to Santa Rosalia about halfway down the Baja Peninsula of Mexico. We were on the Gulf of California side, which meant we weren’t on the Pacific side, and that meant it looked like a stunning, beautiful desert. It was super humid that every single mosquito found me at least once. Relentless.

View of pangas on the shore near the marina, waiting during the day to be launched at night for squid fishing. Photo by Diana Li.

But all of that melted into the background the moment we started getting squids. They were exactly the delight that I thought they would be. They were so cute I had trouble decapitating my first one. I love them so much.

And each night, the lab would pile into our nine‑foot long Livingstone boat and motor out all along the coast. We went and joined dozens of other small boats called pangas which were captained by squid fishers in the city— town. It's really a town. We each had like a bright lightbulb on our boat to attract the squids to the surface. Once we caught the few squids we needed, we just headed back in. But you could turn around and look back out at the gulf and see the pangas still out there like a string of golden holiday lights against the pitch‑black coastline. It's one of my favorite memories to think about.

Each bright dot is a panga along the coastline fishing for Humboldt squid. Photo by Diana Li.

But by week two, all the novelty had worn off and I started to feel really isolated. The only people I could talk to were my lab mates because they spoke English and, for some strange reason, they still can’t figure out all of the Russian that I studied in college just didn’t come in handy in Mexico. I knew I could say stuff like hola, gracias, por favor. I'd just open my mouth and say привет, спасибо, пожалуйста, and it would have been better if I just kept silent.

Plus, we were living in a motel so we didn’t have kitchens for cooking food. The restaurants and food carts were very delicious because I'm now that person that’s like, well, tacos in the US. But seven days in that first week straight of just red meat, I would say my stomach was feeling its own version of isolated. Not quite sick but maybe homesick.

I knew I wasn’t the only one to have poop issues, because we were all talking about it in the lab. If only I could nervous poop now, it would have solved all of my problems.

So the lab tried a new strategy. They were like, “Yeah, what about that Chinese restaurant that we saw every single day driving from the motel to the harbor?”

I was like, “Oh, that place? The place on day one that I told you that I would never go into.” Because I grew up eating the best homemade, authentic Chinese food and I would never debase myself by going to this takeout place. I mean, would the owners even be Asian? I hadn’t seen any Asian people in the town? What’s Mexican‑Chinese food? I don't know. I had like no‑to‑low expectations.

But I got outvoted because, as I said, circumstances were very dire and we went.

So we go and we order all these delightful veggies and rice and all the things that I'm familiar with. It arrives and it's actually not bad. It's not great. The first thing that shocks me is that, oh, I guess it tastes just like regular takeout from the US because MSG should taste the same no matter where you cook it.

The other thing as I was eating, I was getting really emotional. Feeling content with the food, happy, and maybe this word that can only describe it would be gratitude. Like grateful for the first and only time in my life for westernized Chinese takeout.

Anyway, I was so hungry. We ate all the food. By the time we left, the only other people in the restaurant were sitting on the porch quietly eating, so I figured maybe they were the owners. And they had these mannerisms that betrayed to me this idea that maybe they could speak Chinese, so I decided to go find out.

And then not so great Mandarin, trying my best I ask them, “请问,你们说中文吗?” and I got a blank stare.

Then I panicked and just blurted out in English, “So then do you speak Cantonese?”

And they responded. They said, “Si,” in Spanish.

I was like, “Oh, my God. What on earth is happening?” And I was also kind of stubborn. By that point also I got to find out.

I tried again in Mandarin and asked “不说中文?” and this time, their eyes lit up. “啊!说说!” and we were having a conversation. It was incredible. It was exhilarating. The only people in the town I had talked to besides my lab mates the entire time.

It was also terrifying because I was trying to find the right words with my five‑year‑old comprehension of Mandarin Chinese in front of these fluent speakers. But eventually I told them a bit about where my family are from in China and that I'm from the US trying to study squids, but that just got translated into, “I'm here to look at calamari.”

The owners of the restaurant told me they're the only Chinese people in town, and they quickly followed that up with, “We also own the only Chinese restaurant in town.”

And I was like, “That’s fine. I’ll be very loyal to you. It's not like I can talk to anyone else in the town.”

So later that night, back in the motel I was trying to decompress from a very intense evening, trying to figure out why I did get so emotional just eating some fried rice from some corner store essentially. I think back to growing up in the US and finding it really strange, not figuring out why my parents, whenever they ordered Chinese takeout, they would, without fail, each time, eat the food and then immediately disparage the quality.

I mean maybe it's because they were tired of cooking. They would repeat this ritual about once a month. I'm now thinking maybe they got tired not of just cooking but maybe when you have to be the one to create the sense of cultural belonging for yourself in a country that’s not really made with you in mind, either you got to cook the food to get a taste of home. Or you got to just accept whatever version comes from the only Chinese restaurant in town and hope that it's good enough to bring you some comfort to the soul, the digestive system, and make you feel a little lost in a foreign land.

So that restaurant in Santa Rosalia, Comida Beijing, became my new home base for meals. It was great. I never even read their menu. I just went in and asked them to cook whatever I was craving, which was never to the same level as my mom’s cooking, but it tasted just familiar enough. It was really special because I started to feel a sense of belonging in a town where I was struggling to understand the culture and the language.

Actually, over the next three years, I returned to Santa Rosalia a handful more times and, each time, I always made sure to stop by Comida Beijing. And the owners always remembered me. “You’re back,” they would exclaim. “Does that mean the squids are here?”

And I even became Facebook friends with them until I deleted my Facebook which is now Meta. I don't know.

Ironically, none of the data that I collected from all those trips to Mexico made it into my final PhD, because it was just too hard to do, good data collection. But the methods I used I did apply, so it was useful. It was probably not a big surprise to you because of all those experiences I'm just telling about some food I ate one time.

Diana Li, on stage in New York City. Photo by Zhen Qin.

So I tried to ask my parents if my hypothesis about their Chinese‑takeout behavior was correct. And in the true immigrant way, they immediately dismissed my question as trivial and never answered it. I mean, why would we dwell on emotions when I had tests to study for, they had bills to pay and we all had American culture to assimilate into.

At the time, I was really bothered by them not answering this. Now, I realize I don't care what their answer was because the existence of the question started to help me figure out maybe a bit more about them but a lot more about who I am as a person. I'm starting to realize that my heritage doesn’t replace all those other qualities and interests I have.

Yes, that dreaded question is still my least favorite question. Please, don’t ever ask me that question. There's just so much more to discuss, like squids. But even if you must know, and if I do get asked, I try not to get bothered so much because where I'm from and where I'm from from, they're just one of many facets that make me who I am, an Asian‑American scientist who once chased squids to Mexico where she learned a bit of Spanish, a lot more Chinese and a little bit about herself.