I may look like a standard soccer mom now, kids, but back in the day people regarded me as a cross between a rock-star goddess and Darth Vader. That’s right, I was indeed an editor for Nature for nearly seven years, handling papers in genetics and genomics. There is a generally accepted hierarchy in science journals, and Nature is always at or near the top. The team of biology editors at Nature can only publish between about 8 and 10 percent of the submissions they receive, so most of your job as a manuscript editor is not publication of work but instead dealing out rejection.

People ask me all the time what the job was like. The best analogy I've I found is riding the Knight Bus in Harry Potter.

People ask me all the time what the job was like. The best analogy I've I found is riding the Knight Bus in Harry Potter. The Knight Bus is the magical transport full of crazy people and events, both amazingly good and scarily over the top. Similarly, I felt like I was on this magical transport that went to the wildest places, and every week I’d think, “There is absolutely no way we will get to our destination” of putting out a magazine. Yet, thanks in part to the skillful drivers on the editorial and production teams, every week we did arrive at the publication of an issue, and it was an exhilarating ride.

Just like on the Knight Bus, you can't control your seatmates – here, it’s your authors. At one stop the most fascinating, interesting person working at the top of their field will get on, and it is just awesome. You will feel privileged to have met them and have contributed to the magic of presenting their ideas to the world. Then you’ll publish them and they will get off the bus. At another stop, the most difficult, or insane, or just completely incomprehensible person will get on, and submit a paper about hidden messages in DNA or space viruses or something equally entertaining. Unfortunately, you will have to reject their paper, but they are not as happy to get off of the bus. Some of these seatmates will then repeatedly call or email you, most often to cast aspersions on your qualifications, or with some witty rejoinder like “as a woman, you clearly aren't capable of understanding my work, so I request you transfer this paper to a male editor.” The bus keeps traveling, and the cycle repeats.

I was lucky enough to handle an exciting area at a high-profile time: genome papers. These were big productions that had to be wooed for years in advance, and then negotiated and managed like any large project. These papers report determination and analysis of the genetic sequence, or genome, of an organism; Nature was (and still is) interested in publishing them because they are landmarks and resources for scientists in all fields. The human genome had been published before I started, so I first handled the mouse, and then the rat, and then worked through species as they came in. These projects were like the Knight Bus in a second way: If you remember the scene in the third Harry Potter movie where the bus is squeezed impossibly small between two other oncoming buses, that's what it was like to be the editor handling these papers.

On the one side, you have the scientists, who are your customers and your colleagues. For genome papers in particular, there are community-agreed guidelines stating all of the data must be completely freely available, and a history of authors punishing journals by taking their papers somewhere else if the journal does not comply with this openness. On the other side, as an editor you have your actual employer — a magazine with publishers and a commercial side involved. If people have to pay to read papers, and lots of them want to read genome papers, then lots of money is at stake. So the editors are squeezed in the middle, and at times that space can be bloody tight. At Nature, we negotiated the squeeze with a policy that any paper reporting primary genome data for the first time would be freely available under special licenses.

Given the size and importance of these papers, they created mountains of drama. One of the biggest was the chimpanzee genome, on which I had worked with the authors for years, as they had committed to Nature well before the paper was written. This did not stop other journals from attempting to woo the authors by stressing their unique offerings and policies. The consortium of authors and I had agreed that the paper would be freely available, as was our policy, and that we would publicize the findings with a press conference and with extra content bundled into a special, high-profile insert into an issue of the magazine.

The chimpanzee genome spectacle began at the Cold Spring Harbor meeting on the Biology of Genomes in May of 2005. This annual meeting is like the geekiest reunion for the world’s genomicists, with all sorts of side meetings and wheeling and dealing. You stay in dorms and use communal bathrooms, and stay at the bar until the very wee hours, and you feel lucky to be paying to do so. There is high theatre in the talks, including large consortia cramming in as much science as possible in the tiny, coveted speaking slots. Early in the weeklong meeting, I've been tipped off that Michael Eisen, one of the speakers and one of the founders of the new organization the Public Library of Science, is going to slam Nature in his talk. I don’t know how, and am not too worried, as members of this new group have been publicly criticizing other journals at conferences for a while now. Mike and his colleagues feel that all papers should always be freely available, and that the special allowances we have for genome papers should both go further than they do and apply to all work. However, particularly in 2005, the financial model to make this happen has not yet been solidified.

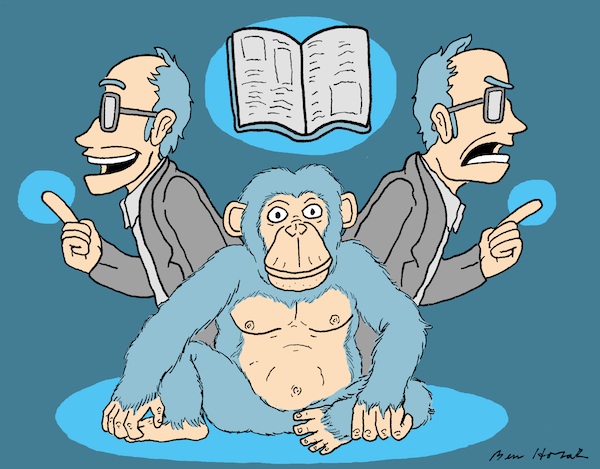

When it’s Mike’s slot, even though he's been invited to talk about his work on Drosophila, he breaks with protocol and instead starts off with a slide showing two pictures of a chimpanzee behind bars, looking tortured. Under one it says Nature and the other it says Science, the other general-interest journal at the top of the pyramid.

I am sitting in the third row with my hands clamped to either side of my head, sporting a look of horror.

Clearly relishing the moment, Dr. Eisen says to the room, “I know that the chimpanzee genome paper is nearing submission, and I want to make a plea to the authors. If you publish the chimpanzee genome in Nature or Science, this is what you are doing to the chimpanzee. You are locking it up behind bars and tormenting it.” Then he adds in the middle a picture of a chimp running freely and happily in a field, and says, “But if you publish in our new open-access journal PLOS Biology, you are freeing the chimp and making it happy.” The audience reaction ranges from annoyance that he’s taking time away from science to delight in the delicious excitement of it all. I do not have a great poker face, so I am sitting in the third row with my hands clamped to either side of my head, a la The Scream, sporting a look of horror and clearly telegraphing “Did he just say that?!” Having delivered the controversy he was looking for, Mike goes on to talk about his research, none of which I remember; when he ends, the kind moderator says, “Well, I think the editors of Nature and Science deserve a chance to respond.”

I am a little passionate about this, because I’ve worked so hard to try and reconcile the academic and commercial sides to allow for freely available papers. So I grab the microphone and say, “Mike, not only is what you said about Nature not true, but you know it's not true. You and I have discussed this, at length, and you know that publishing this paper in Nature will be exactly the same in access as it is for publication in PLOS.”

He answers, “Well, this is more about the general principle of open access. . . .” But that’s not enough of an admission for me. Most of the chimpanzee genome authors are there, and I don’t want them to be misled about a difference in our policies – it feels like watching a political opponent misrepresent a record you’ve worked really hard to establish. Thus I feel the need to follow up with, “Mike, you didn’t talk generally, you showed chimps behind bars. I need you to clarify for the audience that the data you have shown in your talk about Nature magazine imprisoning chimps are in fact false.” Talk about the moments your training never prepared you for. . . .

At this point the moderator steps in and gives the editor of Science a chance, and she has instead cleverly prepared a haiku in response, and she reads that out. And, as is the way of the Cold Spring Harbor meetings, we all talk about it in the bar for hours and make up by the end of the week.

Later that year the paper is finally submitted to Nature. I take the manuscript through a rigorous scientific review process and cut it by at least a third, a standard occurrence by now for these mega-papers. My boss, my colleagues on the team of biology editors, and I compile a beautiful, sixty-four-page special that is the pinnacle of all things chimpanzee. It has the main genome paper plus two related companion papers, and a fourth submission: there evidently had been no fossil evidence of chimpanzees from the past, and a study reporting the first fossil evidence just happened to come in around the same time. I cannot help but rib the paleontology editor that my authors have had to sequence an entire genome, whereas his authors got a Nature paper by reporting on three teeth. But that’s okay – it all passes peer review and goes in, along with four pieces we've commissioned on cognition, evolution, and behavior of chimps. Our news colleagues have put together a beautiful timeline of chimps in science and history, and our production colleagues have put it all through the magical transformation into Nature style and into print, which never got old for me. The only pages I haven't seen are two Nature Publishing Group “house ads” on the inside covers, but they're just house ads and should just suggest you subscribe to the journal or something like that. No problem.

We get to the day of publication, and we've scheduled an early morning press conference at the National Press Club. This is a big deal. Our staff has to be in the office at 6 a.m. for the truck that is coming straight from the printer overnight, because we want people to have copies of the issue at the press conference. Not only do I have a lot of nerves about this huge event, I am now in early pregnancy and having some of the worst morning sickness ever. But I have taken Dramamine and put on my Sea-Bands and so by 6 a.m. I am strapped in and ready.

We get the issues and I only have time to flip through them briefly. They are so beautiful. Our authors arrive to get ready for the conference -- these are brilliant men who control millions of dollars in biomedical funding, like the now NIH director Francis Collins, but it feels like we have been through a couple of wars together with these giant genome projects and press conferences. So even though I went through graduate school looking up to these scientific gods, by this point I think of this group as “my guys.”

At one point before the conference starts I notice two of my guys looking at the issue, and one of them is laughing and the other is shaking his head.

At one point before the conference starts I notice two of my guys looking at the issue, and one of them is laughing and the other is shaking his head. I think, Hmm, that's strange, but don't have time to follow up because we've got so many things to do. For me, one of these things is to take Dr. Collins aside and inform him of my morning sickness situation, followed by the request I am sure he must hear all the time: “Francis: if I throw up or have to run out of the room, you are in charge of the press conference, okay?” Francis Collins, ever the diplomat, does not even bat an eye and agrees to step in if he’s needed. Luck is with me, and the Dramamine holds.

All of the cameras and press assemble, and the conference goes splendidly. The reporters ask lots of questions, and we are prepared this time for questions like “Where is this animal now, the one whose genome was sequenced?” (Unfortunately we didn't have a happy answer for the mouse, but for the chimp, we know where he is and that he’s doing quite well.) Everything goes great. We’ve done it! A large team of scientists has created an amazing resource with the chimpanzee genome sequence, and we feel like we conveyed the findings and meaning of this resource to the press. My guys and I are standing around afterwards exchanging congratulations when one of them, Eric Lander, comes over to me with a big smile.

He says, “Chris, just a beautiful job, it looks so great! We had one question though. We were wondering if you saw all the pages in this special insert.” Frowning slightly, I reply, “Well, yes, of course, except for the two house ads, which were added later.” He laughs and says, “Yes! That's funny! That's what we wanted to talk to you about. Uh, you do know that this is an orangutan, right?”

I blink, not understanding, and answer, “What? What do you mean?” He opens the issue to show me. Remember the house ads, the only part of this years-long project that the editors didn’t see in advance? The one right behind the special inner cover of my beautiful collection of the pinnacle of all things chimpanzee says, 1 September. Nature is proud to publish the chimpanzee genome. This proud message is written underneath a large picture of an orangutan.

And that, kids, was when I learned what it feels like to be run over by the Knight Bus.

Chris Gunter is a geneticist, editor, writer, and nonprofit strategist. She is director of research affairs at HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology and owner of Girlscientist Consulting.

Art by Ben Horak.

For more stories of the drama behind the scenes of science, check out our January 22 show, "Behind the Scenes," at Union Hall in New York.