“The adventure has begun!” shouted one of the station staff as my two friends and I struggled to heave our backpacks onto the train for the first leg of a journey from Toronto to the Cree First Nation of Kashechewan on the shores of James Bay. As an eager engineering student with a passion for science teaching, I had volunteered to be an instructor in a pilot science outreach program for Cree schools and a summer science camp. My classmates were on their way to exciting locations, like Bolivia and India, volunteering to build water filtration systems and work in medical clinics. Why was I instead on a train to the Canadian North?

It’s because I’ve been a science teacher as long as I can remember. People say that about writing or being an artist but not usually about science teaching. For me, though, it’s the truth. When I was a six-year-old, my godfather built a miniature schoolhouse in our backyard. It had a beautiful row of antique school desks, complete with ink wells, that my mom had found when her school was renovated. My poor unsuspecting neighborhood friends were made to sit in those desks and be my students. I had a science and fiction library and made little cards for all the books. They couldn't borrow the books unless they signed them out and gave me the card. I bribed them with Popsicles to listen to me lecture on important topics, such as why the Hindenburg shouldn't have been filled with hydrogen. I really have been a science teacher for as long as I remember.

Our job was to be excited about science, and for someone with a passion for science education, it was a dream come true.

Because of that love, I eagerly signed up to be an engineering outreach volunteer during my first year of university. We visited local schools to give workshops, hosted science days for elementary school teachers, and, best of all, ran summer science camps for elementary and middle school kids. Our job was to be excited about science, and for someone with a passion for science education, it was a dream come true. In a typical workshop or camp session we’d arrive enthusiastically with a crate full of cool materials and start off with a quick demo to get the kids’ attention. We’d dip stuff in liquid nitrogen, set bottles on fire, or make luminescent chemical reactions (mostly, though, the kids just wanted more fire). Then, we’d teach them a scientific concept that we thought was interesting. We would teach them about kinetic energy or aerodynamics and then give them a challenge project that asked them to use the new concept. The basic premise was, “Here's something cool we know, now here's something you can build or a problem you can solve with it.” This formula worked well, and we were booked solid through the year.

Boarding the train in Toronto, we had the same thing in mind for our northern students, with addition of probably a few more mosquitoes. Our first stop was the town of Cochrane. After a few days there, we boarded the Little Bear train, a mixed freight and passenger line that used to run three days a week to Moosonee at the mouth of the Moose River, the entry point into James Bay. There were no scheduled stops between Cochrane and Moosonee, but the train could be flagged down anywhere along the route. As we passed through boreal forest and into the muskeg, we picked up a lone bearded kayaker on a three-month solo trip, a family on their way to Moosonee for supplies, and two young men hoping for a night out in town. After a few days on the nearby island of Moose Factory, getting settled in to life in the north and establishing what would be our base camp, we boarded a tiny six-seater plane to make the final leg toward Kashechewan.

Kashechewan is a fly-in community (in the summer, anyway) with no permanent roads that extend outside of the boundaries of the town. And, as it’s nestled close to the banks of the Albany River, those boundaries are absolute, marked by a circular, ten-foot-tall clay and dirt dike built to keep the flood waters out. In the summer, the dike created a permanent feel of being in a dust bowl, or mud bowl, when it rained. The beautiful banks of the river and even the stunning sunsets could only be seen by climbing up on top of the dike for a walk around the perimeter of the town, something that became an evening ritual for us.

My friends and I found ourselves living in a house with no furniture, in a town where only some of the homes had electricity.

And so it was after two trains and a rough landing in a tiny plane that my friends and I found ourselves living in a house with no furniture, in a town where only some of the homes had electricity. I don't mean that some chose not to have electricity or that they couldn't afford electricity, but that much of the town didn't, at the time, have infrastructure for power distribution. Not far down the road from us was the dividing line. On the other side was Goodwin Video. Actually the sign said Goodwin, Video. So it quickly became affectionately known as “Goodwin Comma” to us. At Goodwin Comma you could rent movies, mostly old ones—I think I watched An Officer and a Gentleman five times that summer—but movies nonetheless. Goodwin Comma was in the part of town that didn't have power, though, so while we could rent a movie there, the people who owned the store couldn’t even watch one.

Also sitting out on a wooden shelf at Goodwin Comma was a shining row of warm Diet Coke. It stands out in my mind not because I love Diet Coke (though I do) but because those warm Diet Cokes were cheaper than the bottled water that had to be purchased for drinking. The tap water was so full of iron that it was red and dangerous to drink. Even when the water system was upgraded after we left, the town remained on a mandatory boil-water advisory due to E. coli contamination. Nearly 60 percent of the community’s population was evacuated for water-related medical attention in 2005. It wasn’t uncommon to see toddlers drinking soda out of baby bottles because bottled water was more expensive and only available on weekdays.

Not yet used to carefully planning our water usage, we found ourselves on the Canada Day long weekend with about half a gallon to share between the three of us. We each placed three small juice glasses containing the remaining water in the fridge and agreed that we could each decide how to use our individual rations: for drinking, brushing our teeth, or cooking. I choose to drink mine, one each morning, and settled for jam sandwiches for dinner. I’ll admit that I was tempted by the end of the third day to do like our neighbors and collect a bucket of water from the river despite the health risks.

Our first day at the school was disheartening as we found few supplies to work with, little natural light because the windows were boarded up, and graffiti on most of the walls.

Our first impression was that Kashechewan would be a very difficult place to live. We heard was that the entire nursing staff from the hospital had banded together to charter a plane and leave en masse due to poor working conditions. Our first day at the school was similarly disheartening as we found few supplies to work with, little natural light because the windows were boarded up, and graffiti on most of the exterior walls. The kids we met in the hallways were bright and inquisitive, though, and openly curious about our presence. They didn’t hesitate to ask not only who we were and why we were there but if we had kids ourselves, if we had boyfriends, and if we liked to go to parties. We found out that many of the kids were experienced hunters, and to the delight of the younger ones, some of the older boys could call geese down to land in the schoolyard.

Three of the older girls, eighth graders I think, took me in and agreed to be my guides. Saskia, Terry-jo, and Shirleyann took me to the best swimming spots, told me which boys were trouble and which teachers were nice, and most importantly, told me that I shouldn’t talk so much.

“Just listen, eh,” said Shirleyann with a wink as part of her instructions on how to be more Cree. I didn’t realize at first how important her instructions would be. She also helpfully noted that baggier T-shirts would be good too.

Kids like this renewed our excitement about being there. We wanted to share our love for science with them just like we had in the southern schools. In the days leading up to the camp, we met with elders who would be special guests. We really wanted this to be a partnership program, one that helped kids see the connections between their community’s knowledge and the scientific knowledge that we could share. We worked with the elders to plan trapping trips and thought about how to discuss the chemistry of dying animal hides. We planned lessons on what caused the elasticity of willow branches and why they are well suited to building rabbit traps.

But while we tried to make connections to traditional knowledge, the science stuff we did was really the usual. We built roller coasters, designed paper airplanes, and did an egg drop challenge, which the kids loved. We built bridges—actually no, I shouldn't say that. We tried to build bridges. We started the activity as we normally did, by asking, “What do you notice about the shapes you see in bridges?” Usually when we asked this question at one of the southern schools, kids would respond by telling us about the trusses they'd seen or about the shapes of the hanging cables in a suspension bridge. But there were no bridges anywhere near Kashechewan and most of the kids had never left the community other than to take the ice road to neighboring Attawapiskat or maybe to Moosonee. We were slow to realize what was going on when the kids were silent, despite Shirleyann rolling her eyes.

Shirleyann was right: We should have listened first.

Finally though, we clued in and asked them what they liked to build. Jo-Willy told us about a bush shelter he’d built with his grandfather, and Joseph took us outside to see the long poles lying in neighboring backyards. They would form the structure for the winter tents erected outside the town in the late fall and used the same engineering principles as the bridges we had in mind. Shirleyann was right: We should have listened first.

Like lots of science camps, we planned on building model rockets. Model rockets fall into a category with space and dinosaurs. They’re pretty much guaranteed to be fun and exciting as a science activity. And while the bridge-building activity relies on kids having experience with bridges, rockets don’t seem to have the same requirement. Most kids don’t have firsthand experience with rockets.

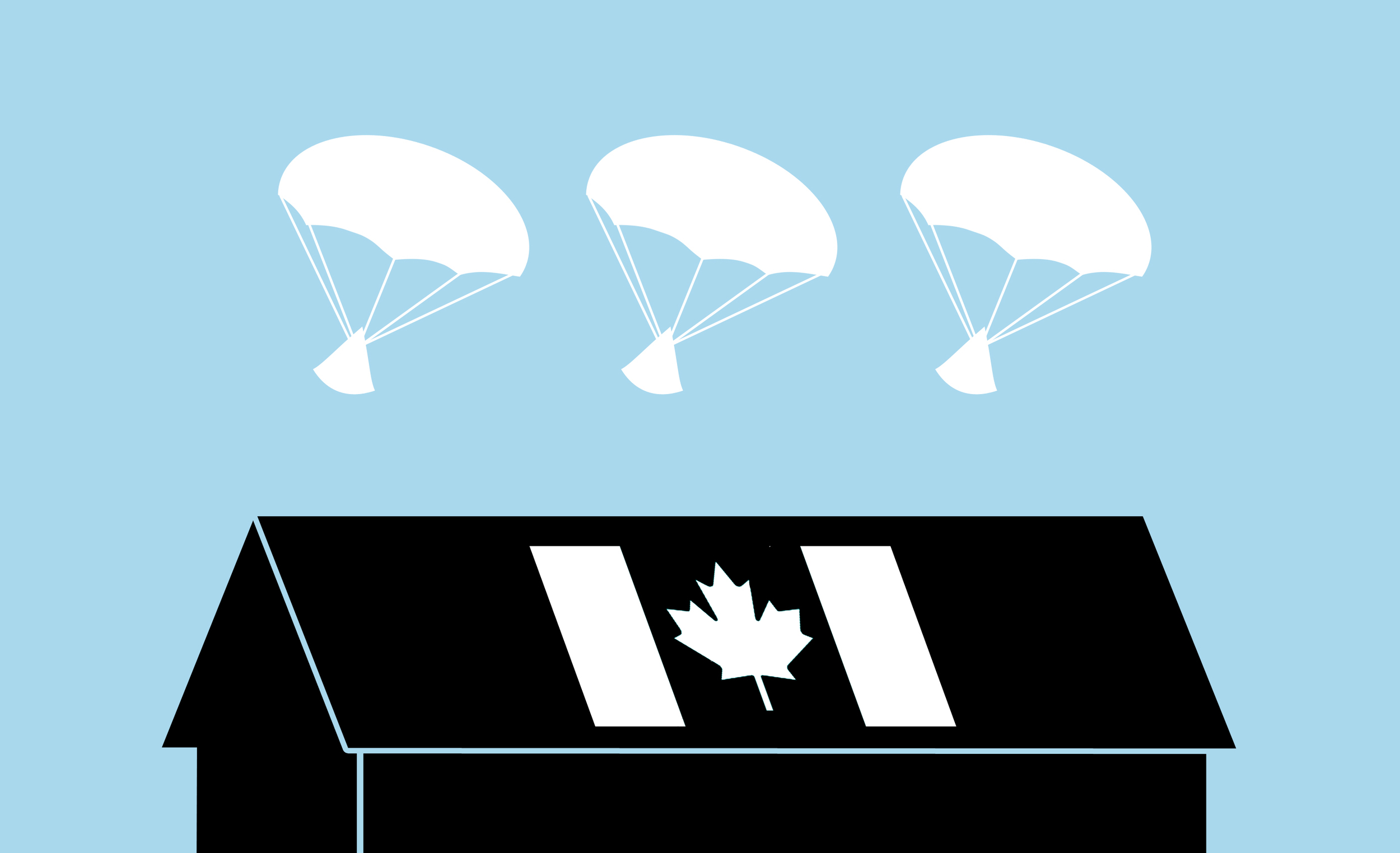

As expected, rocket day was super fun. The kids were enthusiastic and approached the materials with the usual awe and excited reverence. They carefully folded the parachutes into the plastic nosecones and paid close attention to the angle of the fins so their rockets would fly straight. They ran outside with big smiles on their faces to launch them. The launch day wind, though, was a bit stronger than we expected and to the kids’ delight the rockets landed all over town. They were on people's roofs; they were in the hospital parking lot. They were everywhere! Jo-Willy and a group of his friends tried to hatch a secretive plan to collect them from neighboring yards without setting off the guard dogs.

On the second to last night of camp we held a family science night. The kids invited their parents, grandparents, brothers, sisters, neighbors, and friends to hear about what they’d done at science camp. The shelters and roller coasters they had built were on display so the kids could show their families. Some of the older kids did a chemistry show entirely in Cree for the grandparents and elders. The parents would come and speak with us about what their kids had been doing for the past few weeks. Many of the adult family members didn't speak English so the kids would translate for us and talk about the activities they had done.

Near the end of the night, a grandmother approached me. She was very small, had her gray hair tied in bun, and was dressed in several layers of clothes: a black dress, a brown apron, a red blouse, a green sweater, a blue winter jacket, and large black galoshes. She walked up slowly and she stopped in front of me and, for what felt like several minutes, didn't say anything. I stood there confused and finally thought, Oh, maybe she only speaks Cree. Where's her grandson, Jo-Willy? Maybe I can find him to translate. I’d just started looking around the room to see if I could spot him when she started to speak in a slow, careful, thoughtfully considered tone. She said clearly and deliberately, “It's good that you're here and that you want to teach our kids, but why are you teaching them to build weapons? If that's what you're here to do, I don't think you should be here.”

I was stunned, shocked. It was as if someone had just punched me.

I was stunned, shocked. It was as if someone had just punched me. Hurt and confused, I couldn't even muster a response. I didn't know at all what she meant and by the time I had collected myself even a little, she was gone.

I didn't know at all what to make of her comment. I went home and talked to my friends and they were as perplexed as I was. We really didn't know what she was talking about. “Weapons?” we thought. “We built shelters and roller coasters. We built rabbit traps, and we launched rockets. This is all fun stuff, not weapons.” So the next day at camp I asked the kids, “Do you know what she meant?” Terry-jo and Saskia just shrugged. Shirleyann raised her eyebrows a bit but didn’t say anything. The most we could get from any of the kids was a mumbled, “Um, I don't know.” We could tell that they were a bit uncomfortable. Finally Joseph, Jo-Willy’s friend, said, “You know, rockets sometimes mean something different here. They used to do like tests and stuff.” He said it quickly and then turned and walked away.

I was speechless again, this time not out of shock but out of embarrassment. Everything started to come together. The Canadian North, like a lot of sparsely populated areas seems to be a place where it’s okay for satellites to crash and missiles to be tested. Most southern adults’ imaginations had been stirred by the Apollo missions and the space race. Rockets meant progress, national glory, and futuristic thinking. Older Cree had grown up in residential schools or with their families on the land. Rockets can instead evoke images of satellite crashes like the Cosmos 954, a nuclear-powered Soviet satellite that broke upon re-entry in 1978 and showered radioactive debris on thousands of kilometers of the Northern landscape. Warnings had to be posted throughout the area and the Canadian government struggled to explain the debris in languages that did not include words equivalent to radioactive or atomic. The translation became, rather simply, Stay away. Don't touch. Danger, burning. Being here can cause sickness. Rockets might also evoke the 1983 agreement allowing the U.S. military to test air-launched cruise missiles over Alberta, Saskatchewan, and the Northwest Territories to simulate the climate of the northern Soviet Union. Rockets aren’t just about imagination and reaching for the stars. They are also weapons.

What I realized the moment Joseph spoke was that we hadn’t even stopped to think about the science we were doing, about what it actually meant. Despite making some simple connection to Cree culture, we’d taken the same model and gone to these communities and thought, We’re going to tell you something cool that we know and convince you to be as excited about it as we are. Beyond some thinking on the surface that it would be nice to use science to connect to things we thought the kids might be interested in, such as hunting and dying hides, I hadn’t stopped to listen at all to understand what the science we were doing actually meant to the community and the kids. I didn’t even think to ask the question of how something like a rocket might be interpreted.

In that moment, I think my life as a science teacher was permanently changed.

In that moment, I think my life as a science teacher was permanently changed. I’m a science education researcher now, and I study the social context of science teaching. I study the way students and teachers talk to each other and the subtle misinterpretations that can result. Why do I do it? Because Joseph, Shirleyann, Jo-Willy, and his grandmother taught me a lesson I’ll never forget: Thinking about who people are and what science means to them, whether they’re adults, kids, parents, or politicians, isn't just an add-on. It’s not a bonus or just a nice thing to do. And it goes deeper than realizing kids might not have experience with bridges. Thinking about what science means to them is essential. Sitting in my office, a long way from Kashechewan, I still do what I do because, instead of making them listen to me, I finally listened to them.

Marie-Claire Shanahan is a science education professor at the University of Alberta and a former high school and middle school science teacher. Inspired by students like Shirleyann and Jo-Willy, she researches the way people read, write and talk about science and how that influences their choices to participate in scientific discussions and careers.

Art by Maki Naro.

Photos by Marie-Claire Shanahan.