I got a PhD by studying genetics, but somehow never saw this coming.

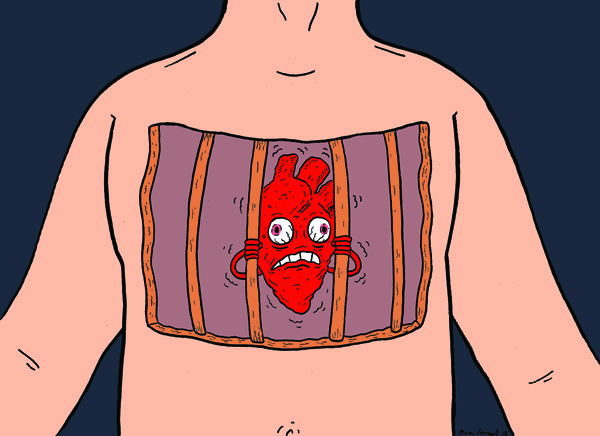

"This" being the night I woke up at two in the morning with my heart pounding, feeling like it had grown tired of life in my chest and was trying to escape. It seemed to hammer against the wall of my ribs as if I had just run a mile at the best pace of my life, even though I had been lying there asleep. Eventually, as it slowly calmed down, I drifted back to sleep, and woke to find my body behaving perfectly normally.

Except it came back the next night. And the night after that. Most people might view this as a sign that it was time to visit a doctor, but this was a few weeks before a major trip to Europe for work, one that would have me meeting Nobel Prize winners and visiting the Large Hadron Collider (I got to know it before it became famous for finding the Higgs boson). So, I took a course of action that has worked well for me in the past: I tried to ignore it and hoped it would go away.

They'd finally caught my heart in the act, and I had a clear diagnosis.

And so I had my late night appointment with my newly deranged heart somewhere over the Atlantic on the red-eye to Zurich. For a day or two, it arrived as I woke up, then gradually shifted back to near midnight as I overcame jet lag. I struggled through a tough couple of weeks and went to my doctor as soon as I got back. It was a little tough to pin down what was going on, given that the attacks only seemed to hit late at night and my doctors only worked sane hours, but eventually it hit one afternoon while I was on the subway. I headed straight to my doctor's office and had her hook me up to an EKG. They'd finally caught my heart in the act, and I had a clear diagnosis.

Atrial fibrillation, or a-fib to its close acquaintances. This, as it turns out, is a disorder my mother had.

Sometime after she turned fifty, she developed a heart arrhythmia. It was never treated with the same level of attention that a heart attack is, but she was on drugs for it for the rest of her life. And every other year or so, she'd have trouble and be stuck in the hospital for a week while doctors tried to find the right combination of drugs to get her heart back in rhythm. She hated the hospital and didn't like to talk about it—she didn't even like visitors while she was stuck there—but she'd always come out and dive right back into life, so it tended to just slip out of everyone's minds as other concerns piled up. I had never asked what the experience felt like, whether it was physically difficult.

But it must have been tough for her. My family has a habit of trying to take things in stride and get on with life, and so she didn't complain unless she was actually stuck in the hospital at the moment. But something about it continued to bother her so much that, as she approached seventy, she was considering a procedure that would provide a permanent fix, but only by burning bits of scar tissue in the heart. Nobody, including my mother, was especially excited about intentionally scarring her heart, so she put it off for a bit, then got busy with other things.

She was still busy up to the day my brother found her in her den, dead of what appeared to be some form of heart failure. But the a-fib was a bit of an afterthought as I dealt with the shock of her loss and then with the business of handling her estate and all the family possessions that had to be handed out or sold off.

By the time that was all done, I'd largely forgotten about the heart condition that had caused all the grief. But genetics had apparently decided it was time for me to learn a bit more.

If you listen to the ka-thump of your heart, the atria are the "ka" portion, where the two upper chambers contract, setting up the lower ones to perform the big thump that propels the blood out through your body. With a-fib, instead of getting a nice clean contraction, the atria just spasm, leaving your heart making more of a bzzzz-thump. The role of the lower part of your heart is much more important—you can get by on the thump alone—so all the doctors were keen to inform me that a-fib wasn't going to kill me.

But damn, it sure could make life unpleasant. For many people, a-fib is completely symptomless. They can be out of rhythm twenty-four hours a day, but the rest of their body goes about its business normally, and they are completely unaware there's a problem until someone catches it during an exam. I was not one of those people. Although I don't know this for a fact, I suspect that, on the bell curve of your average symptoms, I was out somewhere where it goes flat. And not on the good side of the curve.

For whatever reason, the lower chambers of my heart, seeing their partners slacking on the job, decided that they needed to work much harder to make up for it.

For whatever reason, the lower chambers of my heart, seeing their partners slacking on the job, decided that they needed to work much harder to make up for it, which is what left me feeling like my heart was trying to escape being stuck in my body. The rest of my heart tried so hard that the beats would start coming at irregular intervals even as my blood pressure shot up. The whole mess set off an adrenaline response, leaving me anxious and jittery.

And that was the less annoying stuff. The surge of adrenaline generally told my kidneys not to bother wasting energy doing their job, so I ended up rushing to the nearest toilet roughly every hour while an attack was on. And, as it turns out, the nerve that controls your breathing runs right next to your heart. In my case, all that aberrant electrical activity caused my diaphragm to misbehave too. Net result: I burped. A lot. And loudly. Belches actually became a useful diagnostic for me. Unfortunately, even though there was a good reason for having them, they remained socially awkward.

And all of this typically hit at night, which meant I was perpetually sleep deprived.

Normally, I could self-medicate for that by hitting the caffeine, but of course, caffeine is one of the first things you get told to cut when you have a heart condition. It wasn't the only one. Among doctors, I was to learn, a-fib has picked up the colloquial term "friday night heart" because excessive drinking can trigger it even in people with no tendency toward it. So, if you do have a tendency toward it, then cutting out alcohol entirely is highly advisable.

Any of these would have been a bit disorienting on its own. But combined, it just made it feel like my life had gone through a before-and-after transition, and that normalcy was a thing of the past. Suddenly, when I went out with friends, I found myself trying to sort out what the nonalcoholic drink options were. I would pre-apologize in case an episode kicked off while they were stuck in the room with me and, if one did, it typically meant I just went home. I happen to work in a field where most socializing is driven by a caffeine-alcohol cycle, and its big annual meetings have always been highlights of my year. Instead, I found myself leaving the bar early, slinking back to my hotel room and trying to get some sleep.

I found myself trying—and failing—to remember if my mother had gone through any of this. I'm reasonably sure I don't remember her belching, but maybe she was better at hiding it than I was? Were some of the times we thought she was being grumpy or odd actually a response to something only she could feel? In the end, there was really no way to tell, and it didn't seem like she had talked to anyone about it all that much.

In any case, none of it—the sleep deprivation, feeling strung out on adrenaline—made my job as a science writer any easier. But my job returned the favor, and made having a-fib even less enjoyable than it might have been.

Suddenly, any PR that included the word "fibrillation" in the title jumped out like it was lit with red neon.

You see, part of my job as an editor is to track all the science-focused press releases that get put out, and see if there's anything the readers would want to know about. Suddenly, any PR that included the word "fibrillation" in the title jumped out like it was lit with red neon. Some of these weren't especially interesting, and others told me things that I already knew (although wished I hadn't), like the fact that alcohol made matters worse. But maybe once a month, I'd find one that would help me piece together a better picture of the disorder. It was like coming across a nugget of gold in a stream bed.

Or it felt like that until I got to digest the information I was discovering. Reading these releases made it clear that, although a-fib itself wouldn't kill you, having a-fib (as my mother ably demonstrated) could kill you. I'll quote the first sentence of a research paper that my job was kind enough to make me aware of: "Atrial fibrillation is a highly prevalent arrhythmia and a major risk factor for stroke, heart failure and death."

As your atria are spasming, blood tends to sit around with nothing to do for a bit, and will often end up clotting. These little blood clots get sent out from the heart, and lodge in all sorts of inconvenient places, like the muscle of the heart itself, or your brain. Once stuck, they cut off blood flow, causing a small number of cells in the neighborhood to die. You don't tend to pick up catastrophic failure all at once, but your heart and your brain suffer a death of a thousand pin-pricks, gradually picking up enough damage until, as in my mother's case, they give out. And, if the heart manages to hold out, all the mini-strokes in your brain tend to cause age-related dementia to kick in early.

All of a sudden, that surgery where they burned scar tissue into your heart wasn't sounding quite that bad. Unlike the blood clots, the surgeons would presumably exercise some discretion about where they put the scar tissue.

I should have been in an ideal position to decide. A-fib is frequently inherited, and I just so happen to have that PhD I mentioned up at the top. But it got even better. Many of the inherited problems cause subtle changes in how your heart develops back when you are a fetus, and it just so happens I did about 10 years of work in developmental biology. A few of those years were spent in the lab of someone who actually studied heart development. I had actually sat through research meetings with the entire cardiology department of a major medical school.

Figuring out what to do, I was thinking, should be easy.

Except it wasn't. We may know a lot about a-fib in general, but figuring out what's going on in any one patient in particular is really, really hard.

We do know that a-fib runs through families, but it turns out that, in most cases, we don't know the actual gene that causes the problems in a given family. And the genes we do know affect all sorts of different things: how the heart's put together, how cells organize to send electrical signals through it, the proteins that actually help those signals move through a cell. Again, we don't know which of these is the problem in most people. Our treatments, in comparison, are relatively crude. Half a dozen different drugs that tweak how electrical signals are transmitted (not just in the heart, though, which means lots of potential for side effects). And one surgical procedure that involves burning scar tissue into the heart, rewiring it.

For most cases, it wasn't realistically possible for anyone to come to an informed opinion.

Not only did I fail to form an intelligent opinion about what to do, looking into things convinced me that, for most cases, it wasn't realistically possible for anyone to come to an informed opinion. When it came to picking drugs, doctors basically played the odds. If you tried enough of the drugs without success, then you tried surgery.

After a number of drugs failed to get my a-fib under control (although they did succeed in triggering some unpleasant side effects, like muscle weakness and constipation), I ended up with a stark choice: One, try a pill that has side effects that are rare, but so dangerous that you have to be hospitalized for your first three days on the drug. Even if it worked, there would always be a chance that my heart would slip out of the drug's control at some random point in the future. Or, two, I could get my heart rewired, which didn't work out in 20 percent of the attempts, but would provide a permanent fix.

There didn't seem to be any way to sensibly balance the possibilities there. In the end, the idea of a permanent fix had an intangible appeal: if the onset of a-fib had been a before-and-after moment, it seemed to promise a way to switch things back to something closer to before. So I went with it.

The basic idea behind it is that, regardless of what the underlying defect is, a-fib is triggered in part by cells at the junctions where the four veins feed blood into the atria. The procedure involves burning two rings around both sets of veins. The burns end up as scar tissue, which doesn't conduct the electrical impulses that drive your heart's contraction.

Whatever the cells at these veins are telling your heart, the scars act as a sound-proof barrier. With your heart unable to hear the noise coming out of the veins, it's easier for it to listen to the signals that are supposed to be telling it when to beat. The a-fib goes away, at least once year heart has time to adjust to its modified wiring system. In the right hands, the procedure has about an 80 percent success rate and, if some cells happen to grow back across the scar, the doctors can go back in and do some touch-up work. (Thanks to the Internet, I found out that some people have been back in for three or more goes.)

The whole thing is a bit of a high-tech marvel. To get images of how your heart is laid out, they take a sonogram of it—from inside your throat. Thankfully, they knock you out for this. They also do an MRI of your heart. Anyone who's had an MRI done for something other than their heart will know that one of the key instructions for that imaging involves the phrase "don't move!" How do they get a picture of your heart, which is always in motion? They send you inside the tube with leads that register your heartbeat. These are used to time snapshots at the same time in the beat, gradually building up a full picture of your heart.

All that imaging is used to guide two probes, one in each of your femoral arteries, all the way up to and inside of the heart. These carry cameras, electrical sensors to see what your heart is up to, and a small device that emits focused radio-wave radiation, strong enough to burn the nearby tissue. That's the business end of burning scar tissue into the heart.

That said, there were some decidedly low-tech aspects as well. One of them turned out to be the sedative that should have knocked me out for the procedure. Perhaps because my body had spent months without metabolizing any interesting mind altering substances at all, I seemed to have an inordinately high tolerance for this sedative. As a result, I remember coming to several times during the procedure. Mostly, I just let them know I was conscious, and asked for more sedative. But there were two exceptions.

To test whether the procedure is a success, they try to trigger a bit of arrhythmia by setting your heart racing with a big dose of adrenaline. But they didn’t tell me this until afterwards. I just recall coming to, my arms and legs strapped to the operating table, sweating profusely, my heart racing at an insane pace, and fight-or-flight telling me I needed to get out of there fast. Not fun.

The other thing I recall was just a bit surreal. The procedure involves a bit of a balancing act. They pump you with anticoagulants because they don't want blood to clot in your heart as they're busy zapping it. But, at the same time, they open up both femoral arteries, which need to seal back up when it's all over. So, one of my other memories is coming to with my legs spread wide and the nice doctor who was assisting on the procedure leaning heavily, with both hands, into my groin, applying pressure to stop the bleeding.

The sedatives did have some effect. After getting the holes in my groin sealed up, they taped circular balls of cotton over both of them. These turned out to reside in close proximity to my testes, a fact that I found hilarious. Reports are that I was lifting my gown in the recovery room, trying to get people to share in my drug-addled amusement at having four balls.

Overall, the electrophysiologist who did the work found the procedure to be so clean and satisfying that he planned on using the images when teaching a class on the topic to the med students.

But my heart didn't respond like it was a surgical tour de force. I had been warned that the a-fib wouldn't go away right away, but I wasn't prepared for what actually happened: I couldn't settle down into any rhythm for any appreciable length of time. The monitor in my room helpfully identified any arrhythmias that it detected, and it went through a whole catalog, listing a half-dozen different oddities within the span of ten minutes.

After a few miserable days at home, I was back in the hospital as they tried to reset my heart with a cardioversion (the procedure where they yell "clear" right before sending a big jolt of electricity into you—once again, they were kind enough to make sure I was unconscious for this). That bought me about eight fragile hours before I was back out of rhythm. Within two weeks, I was checked back into the hospital for three days of monitoring so that I could start the heart drug that the procedure was supposed to keep me from needing.

But the drug worked. After a few days, I settled down into just a mix of a flutter and fast beats. After a few weeks, the amount of time spent in rhythm was increasing. After a few months, I was going entire days without a problem. At six months after the procedure, the electophysiologist set me up with a device that would monitor me 24/7 for ten days. (Another high tech marvel. The monitor was a Bluetooth device that sent the raw data to a cell phone, which sent it to a central monitoring facility via the phone's data connection.) As part of this, he asked me to take a bold step: stop taking the drug during the monitoring. I could start it again if things went bad.

As requested, I stopped and . . . nothing changed. I still had erratic moments, but these weren't a-fib, and they weren't that often. Better still, things continued to improve even after I went off the drug. By the one year checkup, I had gone weeks without anything happening. My doctor actually used the phrase "We hate to use the word 'cured' but . . ." Alcohol was back on my to-do list, and I even started having a coffee now and again if I needed a bit of an extra push to start or get through the day.

Less than six months later, for no obvious reason, it came back.

Or something's back. It's not a-fib, but it's definitely an arrhythmia of some sort. On the plus side, since it's not a-fib, I don't seem to face the same sorts of ugly health risks that I once did. But in every other way—every way that mattered from the perspective of having a life—it's tough to distinguish. It still tends to come back in response to caffeine and alcohol and, when it does, I still find myself deprived of sleep or struggling with the lack of focus that it seems to cause. Plus I still end up burping, sometimes for hours on end.

And once again, I'm stuck somewhere where that PhD doesn't do me all that much good. It's undoubtedly proved very valuable in helping me understand everything we do know about a-fib. But right now, even though we do know a lot, it's really hard to know exactly what's going on, or what the best way of fixing it is.

John Timmer is science editor at Ars Technica.

Art by Ben Horak.