Just a Fish

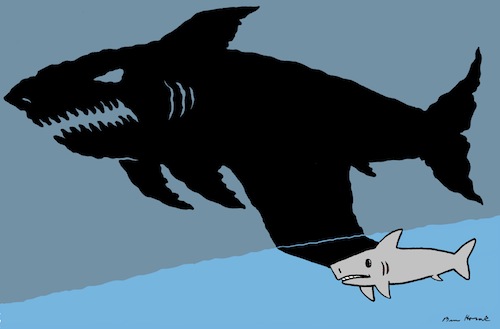

When I was a child, my fear of sharks eclipsed my common sense. Swimming in the family pool alone felt like being abandoned in the middle of the sea—my imagination was larger than any shark. Again and again, submerged in the bright blue world, opening my eyes to the chlorinated sting, I watched as the teeth of the great white came for me. The struggle lasted half a second, the water ran red, and a few hours later my family found my dismembered body stuck in the filter. I cannot recall a single event that spun this web of terror in my heart. Jaws did not help, but I know my fear went back further. Sharks are just scary to a child. Why fear the imaginary monster in the closet when real monsters lurk in dark places? Then again, children and adults fear sharks. People are terrestrial beings; we are awkward and graceless in water, whereas a shark is the epitome of strength, grace and ferocity. Our only defense is to flail and panic, which entices them. Sharks swim straight out of a primordial time when humans had good reason to be afraid of fast animals with sharp teeth. Over the past one million years, human evolution has been dramatic, transforming us from barely bipedal clans of stick-carrying apes to the technological wizards we are today. But in that same stretch of time, sharks barely changed. Their bodies’ speed and agility bestowed them with marine dominance back then, and the past million years of evolution merely sanded the edges of a smooth sculpture. Both species evolved: But while humans were changing, sharks got better at what they already did well. They show no deference for our hard-earned position at the top of the food chain.

Wanting to get the better of my fear, I became determined to see a shark in the wild.

Like most fears, mine was spiked with a dose of curiosity. I spent hours watching documentaries about sharks, studying their serpentine movements, wondering at their perfection, drinking my fear in like a bitter medicine in the hope I would be cured. Still, the nightmares persisted into adulthood, through my studies of marine biology and into my SCUBA diving career. No attained knowledge or logic replaced the irrational fear. That my odds of being eaten by a shark were lower than being run over by a drunk driver, shot with a legal firearm, or attacked by a hippopotamus was irrelevant. I could dive the same reef repeatedly, knowing exactly what to expect. But as long as I was floating at the surface without a view of the bottom, at any moment the great white could emerge. Wanting to get the better of my fear, I became determined to see a shark in the wild. I envisioned diving someplace where sharks were known to reside and confronting them on their turf, but on my terms. I imagined the fear washing away as the object of my intense curiosity swam by in a controlled environment. However, life is unwilling to accommodate our expectations. My first encounter with a shark would pit logic against fear without my prior approval.

In late October of 2005, the SSV Robert C. Seamans left port in San Diego. I was one of the thirty-five crew aboard the boat, a hundred-and-thirty-five-foot sailing machine used for educational and research purposes. Mexico’s Baja Peninsula is about a thousand miles long and it took us several weeks to sail around it. The Seamans ambled through the doldrums at two knots, then turned east around the tip of Baja three weeks after departure. After a port call in La Paz, we headed south again through the mouth of the Gulf of California. Although it was late fall, our decreasing latitude kept the air and water warm. In these increasingly tropical waters we began to see more life – turtles floating alone, a pod of false killer whales eight hundred strong, fin whales, lots of birds. Not just seabirds, but songbirds and hawks lost out at sea, blown hundreds of miles from shore by a rogue wind. Some would perch on our masts and rigging for days before dying of thirst on the deck. Weird fish, too: sunfish, oarfish, flying fish. Sharks.

On a blustery, choppy afternoon, Captain Virginia Land strode across the deck surveying her charge. Wherever Virginia was, she was in charge – she was tall and limber, and carried herself with the bold self-assuredness of a ship captain. Her voice did not match her lanky frame; its sound could carry to any corner of the ship during a gale. The ocean knows as many colors as it does moods, and on this day the overcast sky shone an odd, unnameable color into the sea, and the sea spat it back out through a prism. The tone was a grayish, brownish blue with undertones of electric yellow. It was an uninviting color. But on this unlikely afternoon, Virginia decided the conditions were safe enough for all of us to have a little fun, so she gave out the always-anticipated yell: “Swim call!”

She barked out her instructions to prepare the deck for swimming. Sails needed to be struck. The rescue boat (or small boat, as we called it) had to be lowered into the water and motored around to the port side. I always assumed it was there in case someone got sucked away by a current. The other rules were implicit at this point and needed no specification. The ladder must be lowered to the water. Grab your soap because this may be your only shower for three days. A watchman must climb into the rigging to keep an eye on the bobbing heads below. Do not jump in until the captain gives permission. Only swim on the port side. And swim call lasts for a maximum of fifteen minutes. As a child I never swam in a more supervised environment, but then I never swam in the middle of the ocean as a child.

Furling a sail on the bowsprit a few moments later, I was surprised to see the bustle on deck suddenly stop. Back on the quarterdeck, people were pointing to sea. Could it be a whale? I wondered. By the time I reached the crowd, most of the crew was staring off the port side. Seeing my confusion, the first mate summed it up in one word: “Shark.” Swim call was canceled.

About a boat length away, a solitary gray fin cut through the water with precision, like a knife. We were hove to – a sailboat’s equivalent of parked – and so only drifted along with the breeze. The fin maintained the same distance from the boat, but kept turning around and swimming parallel to our beam, as if the shark knew exactly where we were and did not allow its curiosity to bring it any closer. Being humans, we were not satisfied with this. Someone pulled a foot-long squid, our smelly catch from a few nights prior, from the freezer. He dropped the squid, tentacles dangling, and it hit the water with a weak slap. All eyes rose to the fin, which promptly cut a forty-five-degree turn toward us.

That night I squirmed as I dreamed of water-skiing over a sea so thick with sharks that my ankles stayed dry.

The energy peaked when the shark was within thirty feet of our port gunwale. Cautiously curious, it swam fore and under the bow. I was the first one to sprint the hundred or so feet to the starboard side to see the fin on its return trip aft. Just as the apparition was about to appear clearly below me, gratifying my lifelong anxiety of the unknown, ten or so people ran to my side. When their bodies rammed into the boat’s steel shell, a metallic vibration cascaded from the rail to the hull – the pulse must have continued on through the water, because the shark spooked and vaporized into a world beyond our comprehension. Some who got a good look identified it as a short-finned mako, the ocean’s fastest shark. I never saw more than a few inches of it, but that night I squirmed as I dreamed of water-skiing over a sea so thick with sharks that my ankles stayed dry.

The shark was still with me at breakfast the next morning, probing at my impatient curiosity. While considering how close I had been to staring my obsession in the eyes, I realized how near I had been to seeing it too closely. What if we had been in the water, as we were supposed to have been a few moments later? I posed the question to the captain, who chewed on it like fatty meat. I imagined she weighed the balance of saving lives and not panicking people when she said, “Well, I wouldn’t yell, ‘Shark!’ I’d tell everyone to get out of the water the way I always do – but I would also say to get into the small boat. That would get everyone out of the water quickly.” Though I knew she believed in her calculated response, I wondered how she would react when the sea went white with motion, then red.

Three days and two hundred miles later, the Revillagigedo Islands rose from the horizon without significance. But as the wind drew us closer, the islands’ mystery revealed itself more with each passing hour. Masked boobies began flying miles out of their way to study us, their delicate colorations like carefully applied makeup. Bottlenose and spinner dolphins pushed off our bow. At night their ghostly silhouettes were visible due to the microscopic, bioluminescent life in the water. Isla San Benedicto first appeared as a mountain jutting from the sea, but on the day we arrived at its base we could see the volcano was no ordinary peak: It was a thousand-foot-tall mountain of ash. The massive island looked like the slightest touch could crumble it. Though we could not see into the crater at the summit, its presence was hinted at by the fingers of ash that reached from its lip to the sea and the layers of dry lava that formed inhospitable beaches. The sea was flamboyantly blue, a rich and intoxicating hue that looked ostentatious below the dry, gray mountain.

Planning to spend the afternoon in the otherworldly harbor, we dropped anchor into a massive head of rock and coral, where it became horribly entangled. After twenty minutes of standing aimlessly, watching as the engine tugged us back and forth in an effort to release the island’s grip, the captain saw the potential in all those sets of idle hands. The boat always needed to be cleaned. Though I questioned my logic as I volunteered, I was to clean the bilge. The bilge of any boat is a hellacious place to be for more than five minutes. The mechanical guts hiss and curse; between the unholy stench of oil and diesel and the drunken movements of the boat, nausea is inevitable. The air is so thick, so hot and stale, that your normal bodily functions stop while your skin pours sweat in a defunct attempt to stay cool. I was given what looked like an elephant’s toothbrush to scrub oil stains from the hull – a futile task. For three hours I lay on a hot metal grate and lamely scrubbed at oil stains below me. The tropical sun cooked the steel hull with me inside, and the engine screamed.

By the time I reached the freedom of the deck, we were dropping anchor in a deeper part of the bay. Boobies still flew in circles above us and there was another hour of daylight in the air. The volcano glared down at us, its deep rivulets of ash embracing the sun’s angled shadows. I reeked – my body’s salt formed a film over my skin while the warm breeze dried me. I was surveying the sea’s darkening tones, considering a quick fresh-water shower, when the captain’s voice caught me off guard. “SWIM CALL!”

In two minutes I was back on deck in a bathing suit. Everything was ready a few moments later, the rope ladder unrolled and the small boat in position. Usually the entire crew would turn out for a swim call, but this time only about a dozen people were interested. Virginia gave everything a perfunctory glance and said, “Fifteen minutes. Have fun.” As people began launching themselves over the gunwale, I charged out to my favorite spot – the bowsprit. I climbed across the matrix of rope and stood upright on the tip of the bow, which was as sensitive as an antenna. Out there you could feel every movement of the boat. Each swell and dip would carefully bobble you up and down as though you were standing on water. I stood there breathing in the moment: No lover, no steaming bath, no warm home at the end of a lonely road ever looked so inviting as the unfathomably blue sea below me. Letting out an exultant yawp, I stepped forward and fell twenty feet through space.

The warm ocean pulled me down like an anchor before my buoyancy took over. Instantly, I was refreshed and clean. My head cleared the water and I sighed as my core cooled. Seven people floated near the ladder as I slowly swam toward amidships, about sixty feet from where I had hit the water. And after closing half the distance, I heard her voice.

“Everyone out of the water now! No one else in the water – Everyone out of the water NOW!!!”

The order seemed to come down from the top of the volcano. At first nobody moved. We just got in? people’s faces seemed to say. Why would we get out so soon? Then two things happened that made my heart stop beating. First, my eyes fixated on Ross, the second mate, who was the only one in the water with goggles. He was looking straight down – his neck craning from side to side as though his vision was fixated on something moving slowly, deliberately. For some reason I could not stop watching Ross, which made me privy to his face as he raised it. Staring straight at me, it looked as though his eyes might pop out of his head. Then, I heard the warning.

"EVERYONE INTO THE SMALL BOAT – NOW!”

I did not swim; I skipped across the surface of the water like a stone.

I did not swim; I skipped across the surface of the water like a stone. If there is an Olympic record for a thirty-foot sprint, I broke it. The ladder was clogged with wet bodies, so I shot straight for the small boat. I did not open my eyes, I did not look down. I moved. I vaguely remember that as I reached the Zodiac, I hauled myself up with one arm and a scissor kick. I helped haul three more people in, and the water was devoid of humans in about thirty seconds. For some reason I was laughing – I was giddy, drunk on fear. Somewhere right in front of me, just below the diaphanous surface, my life-long nightmare was waiting for me. On deck, someone pointed and screamed, “There it is. I can see it!” Ross was next to me in the boat, the top half of his body hanging overboard, staring. I had to see it – it was right there! I looked down. Between my feet was a pair of goggles. Unbelieving of what I was doing, I grabbed the goggles and slapped them over my eyes. My hands were shaking fitfully. I could not get them to make a good seal, but I didn’t care. I stretched my torso over the water like a plank, bent at the hips, and dropped half of my vulnerable flesh into a parallel world.

Ten feet away was a sand-colored and elegant form – a Galapagos shark. Ribbons of muscles were wrapped tightly in rough, sleek skin. Its broad snout stretched six feet from the tip of a dramatically arched caudal fin, and everything in between spoke of an uncanny control of motion. The dorsal and pectoral fins sliced through the water like our sails through air. Its eyes were black, windowless rooms, and the glittering outline of waves danced across the shark’s sandpaper skin. Before my goggles flooded with water, the shark’s shape was indelibly etched into my mind, carving a memory so clear I can stare at it without closing my eyes, like a photograph.

I was so transfixed by the silent specter that I felt absolutely nothing – no hesitation, no anxiety, no fear. After all those years of nightmares and dread, the animal before me was nothing that I imagined. It was honest – it was itself. It was . . . just a fish. Just a stunning, beautiful fish. Just as it is easiest to hate what we do not understand, we fear greatest what we have never seen. I had never seen a shark, never felt their magnificent presence. My past experience was limited to a set of irrational emotions, emotions based on events created in my mind. I was like a victim of post-traumatic stress disorder who had never experienced anything traumatic. Looking back at my life pre-shark, when I weigh the bulk of my ignorance against the scope of my understanding, the scale falls over. What surprised me was how little experience it took – a few seconds’ worth – to balance the scale.

That night I had another chance to recalibrate the scale: I awoke to a cacophony of screams above me. Lurching from the bunk, I raced up to the deck. A large floodlight illuminated the water on our port side, and everyone was staring down into the glowing orb. Someone had pulled the rotten squid trick – two figures worked the edges of the sphere of light. The Galapagos sharks were about the same size as the one that showed up for swim call, their motions just as effortless. The tips of their fins faintly rippled the surface before they disappeared. Back and forth, they reentered the glow. I was just getting used to their presence when a monster – a shark twice my length – appeared from the dark. Everyone cackled and pointed down, the way their ancestors must have when danger prowled around the base of a tree in a primordial forest. Their expressions betrayed the emotions I felt in the company of the sharks: fear, for sure, but also a profound awe and wonder. Reverence. This new feeling coursed through my blood and released a dam of ignorance in my heart. When the sharks disappeared, I crawled back into my bunk and slept deeply, dreamlessly.

Jack Rodolico is a reporter for Latitude News. He maintains a healthy — though more rational — fear of sharks.

Art by Ben Horak.