Immortal Popsicle: A Tale of DIY Cryonics

The town of Nederland, Colorado, has a way of sustaining ideas that anywhere else would be untenable. It’s a place you’d have to be a little bit crazy to move to, or that would make you a little bit crazy if you weren’t already. By practical laws, the town itself shouldn’t exist. It sits at the precarious elevation of eight thousand two hundred and twenty-six feet, three thousand feet above my already oxygen-starved hometown of Boulder, and it’s hard to tell whether Nederland is in the midst of being scraped onto or scraped off of the side of the mountains. If Boulder was the inland republic of hippiedom in the 1970s, Nederland is its hardier, spacier, highland diaspora. To Boulder it acts as a sort of aging, grizzled, alternative-living aunt, one who had a bad trip back in the day and has never quite been the same but keeps on tokin’. Whenever I visit, I entertain happy visions of living there in middle age in a repurposed train caboose, having turned out to be someone who plays a rain stick but also keeps a loaded shotgun under the passenger seat of my truck. In Nederland, things claw on to life and refuse to let go—sometimes in the face of science and natural law and all apparent odds.

Perhaps it was inevitable that Nederland became home to Frozen Dead Guy Days and the local human Popsicle for which the Days are named.

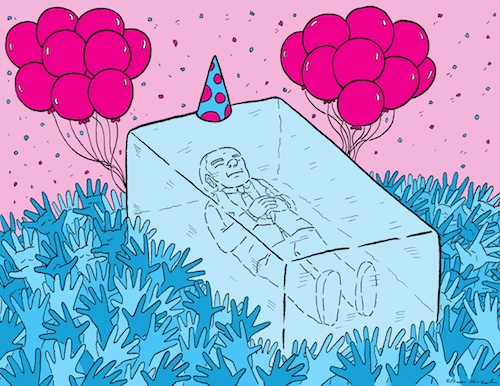

And so perhaps it was inevitable that Nederland became home to Frozen Dead Guy Days and the local human Popsicle for which the Days are named. Frozen Dead Guy Days celebrates “Grandpa” Bredo Morstoel, a man preserved on dry ice in a Nederland backyard Tuff Shed through the dubious DIY cryonics of his enterprising and very devoted grandson, Trygve Bauge, and Trygve’s mother, Aud. Cryonics is at best an untested science. Trygve and his family have not practiced cryonics at its best. They were not scientists licensed in the permafrost arts when they undertook Grandpa’s preservation. Nor did they have whatever governmental permission, if any, might allow them to chill a human corpse in their gigantic homemade cooler. They took on Grandpa’s suspension with little more than a dream in their hearts, an eye on eternity, and a seemingly untappable supply of dry ice. In so doing, they became Nederland’s citizens par excellence and accidental heroes in our species' perpetual arm wrestle with death.

Our story begins when Bredo Morstoel died of heart problems in 1989 while on a trip to a family ski lodge in his home country of Norway. Dutiful grandson Trygve packed Bredo’s remains on dry ice and transported them to California, where, unlike in Europe, cryonics is a legal, if still extremely dubious, science. Trygve placed Bredo’s body in an established cryonics facility in San Leandro called Trans Time. Here the corpse was frozen using a more sophisticated liquid nitrogen treatment, although this superior freezing job may have been too little too late for Bredo. Successful cryonics, at least as science can best theorize, demands that body tissues be frozen completely and immediately after death. Thus it may be that Bredo’s chance at a return from the afterlife was shot the second Trygve attempted the trans-Atlantic journey with Grandpa chilled only over dry ice.

But Trygve has never been a man held back by such stringencies. In fact, he hasn’t seemed to pay much heed to rules of any kind. According to Kathy Weiser of the Legends of America website, before making the climb to live up in to Nederland, Trygve was a resident of Boulder, where was cited for trespassing on the property of the University of Colorado’s president. He was once arrested for threatening—just kidding!—to hijack a plane. Weiser also tells us that as part of his belief in the life-extending effects of the cold, Trygve founded Boulder’s Polar Bear Club, a society devoted to “winterschwimmen.” The club’s most famous practice is the collective leap they take into the county’s frozen reservoir every New Year’s Day. When he lived in Boulder, Trygve was recognized about town thanks to his extravagant beard. His personal Facebook page today features eleven public photos of him floating up to his chest in various frozen Norwegian ponds, the beard swirling and skimming the top of the water. Trygve also has own website, a manic affair with an orange and blue background that explains in scare quotes that “Trygve Bauge & his Trygve's Meta Portal ™ © are both focused on Joyful life-extension ™ © as a motivation, will, goal, philosophy, moral system, legal system, profession, venture combination & way of life.”

But Trygve has never been a man held back by such stringencies. In fact, he hasn’t seemed to pay much heed to rules of any kind. According to Kathy Weiser of the Legends of America website, before making the climb to live up in to Nederland, Trygve was a resident of Boulder, where was cited for trespassing on the property of the University of Colorado’s president. He was once arrested for threatening—just kidding!—to hijack a plane. Weiser also tells us that as part of his belief in the life-extending effects of the cold, Trygve founded Boulder’s Polar Bear Club, a society devoted to “winterschwimmen.” The club’s most famous practice is the collective leap they take into the county’s frozen reservoir every New Year’s Day. When he lived in Boulder, Trygve was recognized about town thanks to his extravagant beard. His personal Facebook page today features eleven public photos of him floating up to his chest in various frozen Norwegian ponds, the beard swirling and skimming the top of the water. Trygve also has own website, a manic affair with an orange and blue background that explains in scare quotes that “Trygve Bauge & his Trygve's Meta Portal ™ © are both focused on Joyful life-extension ™ © as a motivation, will, goal, philosophy, moral system, legal system, profession, venture combination & way of life.”

“He is specializing,” he says of himself in the third person, present tense, “in nuclear war-proof life-extension centers.” He also holds world records for extreme ice bathing.

***

When Trygve moved to Nederland with Bredo in tow in the early 1990s, he purchased property on which he planned to build not only his own cryonics facility, but also a personal fortress, capable of withstanding nuclear attack, for him and his mother. While the facility/castle-bunker was under construction, Bredo was stored in a shed out back and tended to with dry ice. Here, too, Trygve’s science may have gone a little fuzzy around the edges. The shed was kept around somewhere around negative one hundred degrees Celsius, about two hundred degrees warmer than a professionally maintained cryonics freezer would be kept. Despite the questionable conditions, soon a second body came to join Bredo. The family of one Al Campbell, formerly of Chicago, had heard about Trygve’s undertaking and sent their beloved to join Grandpa in the shed. Grandpa and company stayed cool and remained unknown to the people of Ned for at least half a year while Trygve and mother tinkered on the anti-nuclear castle and kept restocking the dry ice.

Then, around the time he broke another winterschwimmen record by sitting for over an hour in a gigantic vat of ice, Trygve was called out on an expired visa and deported back to Norway. Trygve’s mother, Aud, assumed all corpse-tending duties until she was threatened with eviction from her house—not, ironically, for the bodies out back, but for living in a building without running water or heat. The authorities were only tipped off to Grandpa and friend’s presence when a distraught Aud revealed to a reporter her concern about Al and Bredo thawing out. Al was quickly reclaimed by his family and extricated from the affair, but the matter of Grandpa once again refused to die. After much media uproar, attempts by the city to send Grandpa back to Norway, and increasingly strong local calls to let the body stay, Grandpa was permitted to remain in his shed and grandfathered (so to speak) into a city ordinance otherwise banning homegrown cryonics.

If this sounds at first to be opportunistic, possibly in poor taste, and more than a tad macabre, you wouldn’t be wrong—and that’s exactly why I love it.

This might have been the end of Bredo’s story some other place in America, but Grandpa’s legend took root in the weird-nourishing, anomaly-sustaining soils of Nederland. The town parlayed Trygve’s scheme into an enterprising scheme of its own—the annual Frozen Dead Guy Days festival to be held in Bredo’s honor. The festival has been running for eleven years now. If this sounds at first to be opportunistic, possibly in poor taste, and more than a tad macabre, you wouldn’t be wrong—and that’s exactly why I love it. After all, what better way to build upon Trygve’s enterprising spirit? And what better way to revise death’s relationship to humanity than by spending a weekend racing in coffins? During Frozen Dead Guy Days, death is no longer the enemy but the cause of celebration—and anyway, it’s only temporary. Some locals are still not sold on the holiday, but Trygve seems to approve: according to the official Nederland Frozen Dead Guy Days website, Trygve termed the festival “cryonic’s first Mardi Gras.” Celebrations are often presented under sponsorship from the good folks at Tuff Shed, who were also kind enough to upgrade Grandpa’s digs. Frozen Dead Guy Days encapsulates the way Nederland and Grandpa’s two weird forces have come to sustain each other. Grandpa boosts town revenues and the town makes sure its number-one citizen doesn’t get freezer burn.

Aside from Bredo, no one can be said to be more bound up in this transmortal symbiosis than Grandpa’s present cryonic caretaker, Bo Shaffer. Known as “The Ice Man,” Shaffer makes his livelihood by tending to Bredo in his permafrosted state. Because Trygve has only been able to come to Nederland once or twice since his deportation, he hired Shaffer to tend to Grandpa in his stead. Now a local celeb in his own right with a published book about his work, a bungled invitation to appear on Jay Leno, and a rather distinctive mustache of his own, Shaffer is as charming a personality as the rest of the Frozen Dead Guy Days cast of characters. Shaffer’s primary duty as caretaker is to schlep one thousand five hundred pounds of dry ice from Denver to Nederland every few weeks to re-pack Grandpa at Trygve’s expense. This is accomplished with a flatbed truck painted with the stars and stripes, a pair of thick gloves, and the odd thick-gloved volunteer.

Shaffer chronicles all this on his “Iceman’s Log” website, a record of Grandpa’s attendance kept in twenty-four-point font in a palette inspired by Lisa Frank. Most entries feature a snapshot of the coffin, tucked amongst the dozens of bricks of dry ice in the “cryonic chamber” and wrapped in frost-licked chains like something out of Scooby Doo. Apparently, Shaffer isn’t as startled or bemused by this scene as I am when I look at the pictures. With a fabulous nonchalance and earnestness about the cause, Shaffer’s entries usually make a remark or two about how pretty the drive up the canyon was, then note the chamber’s temperature, the amount of ice added and what, if any, baked good he or his volunteers brought to share with Bredo. “The crew did a great job and enjoyed hanging with Grandpa,” Shaffer wrote of the April 2012 visit. “A little cake, a little Old Grandad on dry ice . . . a good day’s work!”

What makes Trygve exceptional is that he had the guts to take matters into his own mitten-clad hands.

If Trygve’s bold at-home experiment seems egomaniacal, delusional, and wildly unattuned to the conventions of medical thinking, again, you wouldn’t be wrong. And again, that’s what makes it so great. While Trygve’s tool shed tinkering falls outside the established order for amateur science projects, the impulse behind it does not. As a species, we’ve been pushing back against death for as long as we’ve been around. Nor is Trygve the only person to think that popping a deceased relation in the freezer might help them literally live to see the day when medicine had evolved enough to cure what ailed them. (Larry King, for one, has already purchased his place in a fridge; rumor has it that Paris Hilton is considering her options.) What makes Trygve exceptional is that he had the guts to take matters into his own mitten-clad hands; he went renegade with a sort of heroic disregard for what the operating rules of medicine and the known universe suggest is possible. It’s this kind of disregard that I suspect makes for the very best—and, okay, maybe also the very worst—stuff of science. Perhaps the most unfathomable scientific breakthroughs can come only to such a mind as much fantastical as realistic, one not unduly burdened by the constraints of logic and apparent natural order and maybe even morality. Trygve attempted to renegotiate of the rules of life and death with (as I imagine it) a pair of ice tongs and an oven thermometer, and for this we must celebrate him.

***

The last time I was home for Frozen Dead Guy Days, I took in the Parade of Hearses and the Coffin Races. I watched as young and old alike dunked themselves through the hole in the ice on the old mill pond, a feat so obviously unpleasant that home cryonics began to seem like a saner formulation of life extension through extreme cold than Trygve’s Polar Bear Club. I skipped the frozen salmon toss, the Grandpa look-alike contest, the Blue Ball dance party, and the Frozen Chocolate Tour, the snowy beach volleyball, the icy turkey bowling, and the screenings of Grandpa’s in Tuff Shed and its sequel. With the exception of the snowy beach volleyball, which looked fun if also very cold, it was not that I didn’t want to participate. It was just that I go for the feeling of the fête as much as for the festivities. Frozen Dead Guy Days revels in the morose and makes light of the dark, and in so doing, undoes death’s hold on us a little.

The fact that Trygve’s scientific ambitions are, at least for the present, untenable makes me only admire them the more.

But the best thing about the way the festival thumbs its nose at death is the feeling behind it. Frozen Dead Guy Days derives its energy from the devotion behind Trygve’s extreme science experiment, and that most human and humanitarian of wishes not just to outsmart death but to do so for the ones we love. The fact that Trygve’s scientific ambitions are, at least for the present, untenable makes me only admire them the more; it’s as by if sheer force of passion and sub-zero cooling, Trygve thought he might be able to rework what is nature’s most immutable law. Trygve’s a guy who makes being a mad scientist (and anti-nuclear-castle-builder and ice-dipper . . .) look not just good but valiant. I’m not a Nederlander and I’m certainly no Trygve Bauge, but I’d be glad to be at all like either. If I never try to keep my family around for the next available lifetime via oversized Coleman cooler, it won’t be because I don’t share Trygve’s desire—just his hope that it might actually work.

Emma Komlos-Hrobsky's writing has appeared in Hunger Mountain, Verbal Pyrotechnics, and The Splinter Generation, among other places. She is an editorial assistant at Tin House magazine and a lover of seeds and Neil Young.

Art by Ben Horak.