Death Becomes Me

The first time I died, I was twelve years old.

My friend, Peter Archambault, and I were riding our bikes on Ascension Street in Blackstone, Massachusetts, when we decided to toss our bikes over a cliff on the edge of the street. Don’t ask me why. We were boys. These are the kinds of things that boys do.

The bikes fell about thirty feet, landing squarely in a pile of fall leaves that the wind had collected at the base of the cliff. After a moment of laughter, we began climbing down the rock face in order to retrieve our transportation home.

Peter started down first and saved my life.

About five feet from the ground, Peter dropped into the leaves and was immediately swallowed up by a swarm of yellow jackets that rose up and filled the air, stinging him more than two dozen times. Peter screamed for help as he ran through the woods in the direction of his home at the other end of Ascension Street, giving me time enough to climb back up the rock face and out of danger.

Later that afternoon, after Peter had been iced down and given a large dose of aspirin, his father brought us back to the cliff in order to retrieve our bikes. Before leaving his house, Mr. Archambault asked if I wanted to call my parents and warn them that I would be late coming home, but I told him it wouldn’t be necessary. I was twelve years old, but it had been at least two years since I had been living under a curfew of any kind. Ever since the fifth grade, when I started babysitting my brothers and sisters into the wee hours of the morning while my parents went out drinking with money we never seemed to have, I had been operating with little parental supervision. While Mr. Archambault would expect Peter to call home if he was going to be late, I would not because it was impossible for me to be late. There was no actual time when I had to be home.

Using a horseshoe tied to the end of a length of rope, Mr. Archambault managed to hook my ancient black Huffy by the tire and pull it up from the leaves. In the process, a single yellow jacket accompanied my bike up the cliff face and stung me on the thigh. It hurt, but I thought nothing of it. I had been stung by bees many times before.

With my bike once again underneath me, I began riding home, sensing the first signs of trouble about a half-mile from my house: a sudden shortness of breath and swelling of my hands and neck. Since I had been stung before, I made no connection between the single yellow jacket sting and the allergic reaction that I was now experiencing.

The fact that I was pedaling my bike, mostly uphill for more than a mile, did not help matters. The symptoms related to food and insect allergies are often accelerated by exercise. I have a friend who is highly allergic to soy who had been eating a certain brand of energy bar for years without a problem. A month ago she ate the same energy bar just prior to an aerobics class and nearly died after suffering an allergic reaction. Absent the exercise, the trace amounts of soy in the power bar had no effect on her. Add an hour of high-impact cardio and it had suddenly become deadly.

By the time I arrived home, I could barely breathe.

By the time I arrived home, I could barely breathe. I literally crawled up the three crumbling concrete steps to our home, only to find it empty. My stepfather and my siblings were nowhere to be found and my mother was in the hospital, recovering from a recent back surgery. Using all the strength I could muster, I grabbed the phone from the wall, slid down to the cracked linoleum floor and called my mother’s hospital room. Between gasps, I tried to explain my situation.

My mother, acting calmer than I would have ever imagined, immediately told me to hang up the phone and call 911. But this was 1983 and the telephone was attached to the base by a cord, and the base was set high on the wall. In order to disconnect the line, I would need to actually connect the receiver to the base, but I was no longer able to stand. At this point, I was barely conscious.

My mother attempted to hang up the phone on her end but was also unable to break the connection. In those days, both ends of a phone call often needed to be disconnected in order to break the connection and regain the dial tone, so try as she might, she could not get a dial tone on her phone. Instead, she told her hospital roommate to call 911 while she remained on the phone, begging for me to breathe.

She told me later that she listened to me wheeze for a bit before she heard the phone clatter on the floor, followed by silence.

“The worst moment of my life,” she said.

After what seemed like an eternity, my mother heard the wail of sirens through the phone line and eventually heard the shouts of paramedics as they entered our house. They found me on the floor, unconscious, not breathing, and with no pulse. They began CPR immediately.

As they worked, the paramedics had no idea that my mother was listening to everything they said and did on the other end of the phone line. In fact, my mother did not know if they had been successful in resuscitating me when the paramedics finally strapped me to a gurney and rolled me out of the house and onto the ambulance. She heard sirens blare as the ambulance began the trip to the emergency room in the very hospital where my mother was sitting in a bed, listening and wondering if she would ever speak to her eldest child again. She called down to the emergency room and explained the situation to a nurse, who called back after the ambulance had arrived to inform her that I was alive.

"Waiting for the ambulance was the second worst moment in my life," my mother once told me.

My first recollection was opening my eyes under an enormously bright light. I remember blinking a lot and feeling like the blood just beneath my skin was on fire. A nurse said, “He’s awake,” and a doctor leaned in close as if he was confirming the nurse’s assessment.

I immediately asked for my mother.

I had experienced no white light or ethereal tunnel during the time when my respiration and heart rate stopped.

Though the light of the emergency room now filled my vision, I had experienced no white light or ethereal tunnel during the time when my respiration and heart rate stopped. There is no telling how long I was actually dead, but my mother estimated that it was five minutes between the time I dropped the phone and stopped talking and the time the paramedics arrived, though she also admitted that every second had felt like an eternity.

It turned out that I was uncommonly allergic to the sting of a yellow jacket. Every day for more than a week following that sting, allergic symptoms would reappear, beginning with itchiness and the swelling of my hands and feet but before long creeping into my airway once again. I was rushed back to the hospital for additional shots of epinephrine each time until the poison completely dissipated from my system.

When you consider everything that happened that day, I was extremely lucky.

Had I climbed down that cliff first and been stung even twice, I would have surely died. Had I been standing even a foot closer to the edge of the cliff, I might have been the first one to jump into that leaf pile. Had my home been two miles away, I might have died on the side of the road.

The line between life and death is a thin one. Frighteningly thin.

It can also, I would later find, prove to be highly instructive.

***

In high school, I was a procrastinator of the highest order. Though I would graduate in the top 10 percent of my class, I did little by way of homework and studied even less. My academic success had more to do with my ability to write well and endear myself to a few critically important teachers. My grades may have been good, but they did not in any way reflect my work ethic or desire for achievement.

I possessed neither.

I was also growing up in an impoverished household amidst a failing marriage with less-than-attentive parents. The fact that I had no curfew and had been babysitting my brothers and sisters at an exceptionally young age had less to do with my ability to be responsible and more with my parents’ inexplicably poor judgment. My mother loved me, to be sure, but that did not mean that she was much of a caregiver. As I have learned throughout my life, love and the ability (or even willingness) to be a good parent are not necessarily mutually inclusive.

No one had ever said the word “college” to me. Not once in my entire life.

A lack of a work ethic, combined with this failure of parents to parent and an absence of a college fund, offered me little by way of a future. Despite my good grades and bounty of extracurricular activities, no one had ever said the word “college” to me. Not once in my entire life. Not my parents, not my teachers and not a single guidance counselor. While my friends were visiting colleges, taking SATs, and strategizing with Mr. Maloney in the guidance office about first choice and safety schools, I was left wondering why no one was talking to me.

I assumed it was because we were poor (and perhaps it was), and because of this presumption, I was paralyzed, unable to do anything about it. Poverty is an embarrassing state of being, especially to a child. Parental negligence is even worse. Growing up neglected and impoverished in the midst of classmates who were solidly middle class or better, I had learned to conceal my family’s lack of money lest I appear different or desperate. It wasn’t always easy. I had already spent a lifetime bumming rides off friends, borrowing camping gear in the winter months, wearing my cousin’s decade-old hand-me-downs and making excuses for my parents’ failure to attend a single concert, track meet, ball game, or Boy Scout jamboree. I was always the kid without any money for the museum gift shop and the one in need of scholarships in order to travel with the band. I was a free breakfast, free lunch kid in an era when the teacher required me to raise my hand during lunch count to indicate that I would be eating a free hot lunch that day and every day.

To slink my poverty-stricken, parentally neglected ass into the guidance office and ask about college would have inevitably led to questions about paying for college, so my ass remained firmly outside that office, waiting and hoping and praying that someone would come and ask me if I wanted to go to college. But no one ever did.

I was a procrastinating, underachieving, rudderless kid living in poverty with no hope for the future.

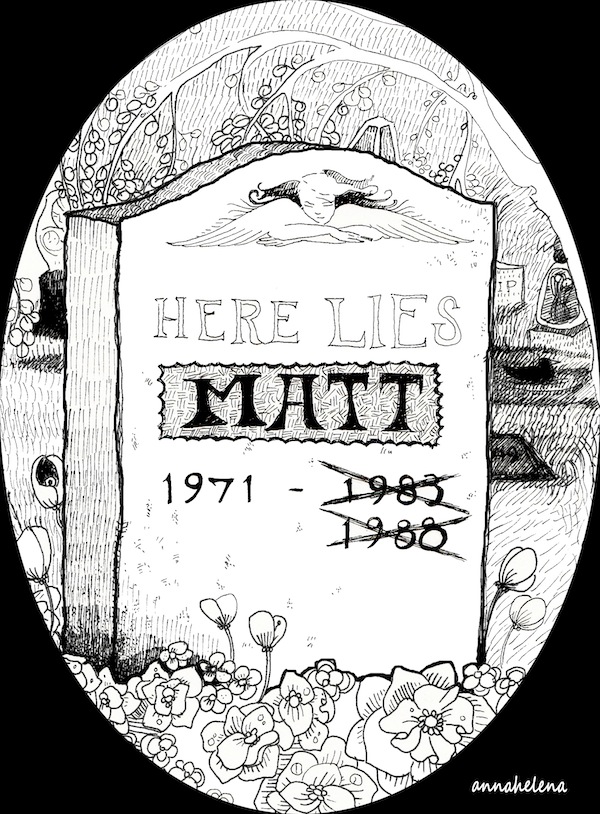

As if the universe was aware of my condition and was intent on helping me overcome these challenges, I died for a second time just five years after my bee sting.

It was December 23, 1988. I was driving home from a day of Christmas shopping in order to pick up my McDonald’s uniform and head off for an evening shift. I was seventeen years old at the time and driving my mother’s 1976 Datsun B-210, and I was feeling pretty good about myself. I was managing the restaurant, working more than forty hours a week in addition to high school in order to avoid being that free-lunch kid anymore, and I had succeeded. With actual money in my pocket, I had been able to purchase Christmas presents for my family members for the first time in my life. Frivolous and fun presents, too, which were the kinds of presents I had not seen in a long time. For the last two years, the gifts that I had received from my parents had consisted of a set of bath towels, flatware, a microwave oven, and a set of pots and pans, presumably in an effort to make me understand that once I graduated, I would need to find a place of my own. With nothing saved for my college tuition and a monthly struggle to even pay the mortgage (my mother would lose the house two years later), I would be living on my own in less than six months, and I was well aware of it.

My parents had made sure of this.

Nevertheless, I was heading home with a car full of gifts, and I was excited about placing them under the tree in the next couple days. It was going to be a very merry Christmas at last.

It had been snowing that afternoon and by the time I was on the road, a thin layer of snow and ice covered the pavement. As I came around a corner and down a steep hill, I lost control of my car and began sliding into the opposite lane. The police later estimated my speed around thirty miles per hour, but unfortunately the Mercedes coming up the hill was also traveling around thirty miles per hour, making our head-on collision the equivalent of driving a car into a brick wall at sixty miles per hour.

I almost always wore my seat belt back then, but shopping had taken longer than I had expected and I was in a rush. In my hurry, I had forgotten to put it on.

Right before we hit, I remember saying, “Oh my God, this is going to suck.”

It did.

On impact, my body was thrown forward. My chin caught the top of the steering wheel, knocking out my bottom row of teeth in one chunk and ripping open my lips and chin. Once past the steering wheel, my head crashed into the windshield, embedding my forehead in the safety glass.

At the same time, my body and legs were thrown forward. My chest struck the center of the steering wheel, driving all the air from my lungs and cracking ribs. My left leg struck the emergency brake release, knocking off the handle and impaling my knee on the thin, metallic post upon which it was attached. My right leg became embedded in the air-conditioning unit, pulling the flesh back far enough to expose the bone.

Thanks to shock, I felt no pain. I knew that my teeth were rolling around in my mouth, but otherwise I felt fine. Even the exposed bone of my knee and leg did little to bother me.

Shock is a dangerous response to trauma, but it can also be uncommonly useful.

I can still recall with chilling clarity the smooth pull of the emergency brake post as I slid it back and out of my left knee.

Moments after the accident, I began extracting myself from the vehicle. I leaned back in my seat, freeing my head from the windshield. I pulled my right leg from the air-conditioning unit, noting the gore that was left behind on the vents and controls knobs. I can still recall with chilling clarity the smooth pull of the emergency brake post as I slid it back and out of my left knee. Just writing about it makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up, but that day, thanks to shock, I thought nothing of it.

Once free, I opened the door of the car and climbed out. I couldn’t walk but managed to hunch down beside my car as the driver of the Mercedes, a middle-aged woman, approached me. She took one look at my battered body and fainted, collapsing to the ground by the edge of the road.

I didn’t know it, but I was bleeding badly from my head and legs and didn’t have long to live.

A truck full of teenagers was the first to arrive on the scene. A kid who was about my age ran over to me, took one look at my condition, and said, “Dude, you’re fucked.” His friends arrived a second later and together they convinced me to lie down in the mud on the side of the road.

A few minutes later, as my body began to grow cold, the first police officer arrived. I saw him lean over and speak to me, but I could not hear his words. I asked about the condition of the woman, and I realized with detached interest that I couldn’t hear my own voice either.

Shortly thereafter, just before the paramedics arrived, I lost consciousness. When the paramedics arrived, they discovered that I had neither a heart rate nor respiration.

Dead again. And once again, no white light. No tunnel.

Somewhere on the way to the hospital, in the midst of CPR, I began to breathe again. My heart began to beat.

As I was rolled into the emergency room strapped to a gurney, I regained consciousness.

In the emergency room, my teeth were wired to my jaw. Glass was picked from my forehead, though I would continue to pick out glass for two years after the accident (once in math class, much to the horror of my classmates). I had surgery on both knees, and ten years later, I would have another surgery when my left knee began spontaneously bleeding from the old wound. A week before the surgery I went to Universal Studios in Orlando and the knee began bleeding while I was on the King Kong ride. As I stepped off the tram, the children who were ready to board the ride began screaming when they saw the amount of blood running down my leg.

I experienced a similar incident a couple days later at Typhoon Lagoon, but this time I had the good sense to yell “Shark!” as the water turned red around me.

The accident caused me to miss out on my opportunity to become an Eagle Scout. It ended my track and field season, thus preventing me from defending my district pole vaulting title. I spent a week in the hospital (including Christmas) and months recovering. I have scars on my chin, lips, forehead, and knees. The teeth in my lower jaw have been dying a slow death, and one has been missing since the accident. The accident also turned out to be one of the trigger events in my bout with post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition that I have battled for more than two decades.

But I was lucky once again, and not because I survived. My survival was indeed fortunate, but the real luck came from dying in the first place.

Or the second place.

I was seventeen years old at the time of the accident, but because I was still considered a child, I was placed in a room in the pediatric wing of the hospital. Outside the only window in my room was a brick wall. Painted on that wall was an enormous rainbow. The nurses explained to me that the rainbow had been painted for a little girl who had spent months battling cancer in the room that I was now occupying. She hadn’t been able to leave the hospital, but the staff had adored her so much that they painted the rainbow for her so she wouldn’t spend her last days staring at a brick wall.

Would anyone have painted a rainbow for me? Had I done anything rainbow worthy?

As I lay in that hospital room on Christmas Eve, alone and in pain, staring at the blender that my parents had given me earlier that day as my Christmas present, I began thinking about that little girl who had died in the room where I was now celebrating Christmas alone.

That’s when it occurred to me. I’d died, too. Twice in fact. Just like that little girl, my heart had stopped beating and I had ceased to breathe. Had EMTs not restored my life twice, I would not be here.

Would anyone have painted a rainbow for me?

Had I done anything rainbow worthy?

I made a decision that night to make something of my life. With an awareness of the fragility of life that bordered (and still does) on terror, I determined that from that day forward, I would make something good of my life. We are constantly admonished to live each day as if it was our last, and at the risk of sounding self-congratulatory, I believe that I apply this principle with a conviction that few approach. There is not a day, and oftentimes not an hour, that goes by that I do not think about my mortality and the ease by which death can be achieved. This ever-present awareness has assisted in the persistence of my PTSD and can often prompt me to great anger or sadness, but it is also serves as a blazing fire in my belly, driving me forward with unrelenting motion.

Dying twice before the age of eighteen created a multitude of problems for me, yet if I could do it again, I would not change a thing. Because of these incidents, I am driven, focused, and constantly moving. I wake up each morning with the knowledge and conviction that each day could be my last. I spend my waking hours wondering if this will be the last time I hug my daughter, the final time I witness a sunset, the last time I hear The Beatles sing about Desmond and Molly and their home sweet home. I go to bed every night, angry about my need for wasteful, unproductive sleep, wondering if I can shave another minute or two off the scant few hours I already spend in bed.

I have died twice so far. For a person growing up under the conditions that I did, I cannot imagine a more fortunate set of circumstances. I would not be where I am today had a bee and a Mercedes not tried to kill me.

For a long time, ever since I was a boy, my dream has been to “write for a living and teach for pleasure.” For the longest time, this dream seemed impossible. Fanciful. Ridiculous.

Today, I am an elementary school teacher in West Hartford, Connecticut. I have been teaching for fourteen years. I am a former West Hartford Teacher of the Year and a former finalist for Connecticut Teacher of the Year.

In 2009, I published by first novel, SOMETHING MISSING, with Doubleday Broadway.

A year later I published my second novel, UNEXPECTEDLY, MILO.

My third novel, MEMOIRS OF AN IMAGINARY FRIEND, was published in August by St. Martin’s Press. It will be translated into fourteen languages and counting.

I am not writing for a living and teaching for pleasure yet, but I am closer than I could have ever imagined. This is not because I am an especially smart person. It is not because I am more talented or harder working than the next guy.

I am merely a product of my environment, the result of the cessation and resuscitation of a heart beat and respiration. I have been given the gift of awareness. I see the world as a tragically temporary place in which every minute must be seized by the throat and squeezed for all it’s worth.

It’s a lesson learned the hard way, but aren’t all important things, and perhaps the most important things, learned this way?

I suspect so.

Matthew Dicks is an author and an elementary school teacher. He lives in Connecticut with his wife, Elysha, and their two children, Clara and Charlie.

Art by Anna Karakalou.