Awake

I blinked my eyes open. Early morning sunlight sneaked through the blinds on my window, casting a glow on the mess on my floor. Sitting up, I saw my bedroom in complete disarray. There were ripped Hefty bags and stuffed animals spanning twenty-four years strewn across my rug. My room looked like the scene of a barnyard massacre. Looking under my covers, I discovered I was clutching a giant pastel-blue stuffed bunny I’d received as an Easter gift when I was twelve. I could only assume I had spent hours in frantic search of this toy, tearing through our storage areas until I located it. I didn’t remember doing any of that, couldn’t remember the evening at all. But I never could when I was on Ambien. Groggy and confused, I tossed my comforter to the side and started to clean up the mess.

Insomnia had been a part of who I was for most of my life. As an adolescent growing up in Whitestone, Queens, I spent countless nights in my twin bed in the attic staring up at the ceiling, or watching the time on the cable box, waiting for morning. I tried distracting my mind, closing my eyes, and saying good night to my individual body parts, down to the little hairs on my big toe. I’d envision each piece of me turning to sand, each particle floating away on a soft breeze. If that didn’t work, I’d count the words in long songs, like “Paradise by the Dashboard Light.” Nothing helped. At the end of these exercises, I was still awake, thinking about relatives who might die, wondering who would care if I died.

Insomnia had been a part of who I was for most of my life. As an adolescent growing up in Whitestone, Queens, I spent countless nights in my twin bed in the attic staring up at the ceiling, or watching the time on the cable box, waiting for morning. I tried distracting my mind, closing my eyes, and saying good night to my individual body parts, down to the little hairs on my big toe. I’d envision each piece of me turning to sand, each particle floating away on a soft breeze. If that didn’t work, I’d count the words in long songs, like “Paradise by the Dashboard Light.” Nothing helped. At the end of these exercises, I was still awake, thinking about relatives who might die, wondering who would care if I died.

By the time I got to high school a few things changed: I took part-time jobs after school – a clerk at the card store in the Waldbaum's shopping center; an assistant at the dental office I’d been a patient of since I was five. Faced with longer days, I began to combat my sleeplessness with Tylenol PM. Some evenings this helped. On others it didn’t do the trick, and I’d emerge from bed the next morning woozy from the combination of the drug and a sleepless night. On my way to school at St. Francis Prep, I would stop at the corner store to purchase caffeine capsules and gulp them down them with coffee. My hands and body shook all day. I felt everyone could see my heart thumping in and out behind the left pocket of my button-down shirt.

I never told my mother how serious my problem was. Instead, I responded to her “sleep well” wishes each night with “you too,” and I trudged the twelve steps up to my attic bedroom, where I’d spend the next eight hours willing my body and mind to fade out.

I couldn’t share this with her because she had enough problems. I wasn’t willing to present another. My father died of liver disease when I was six years old, leaving Mom to care for my eighteen-month-old brother, Ralph, and me on her own. My brother needed constant attention at home and at school. By the time he turned nine, he had been diagnosed with ADD and OCD. Mom spent her days at work and her evenings taking Ralph to doctors. He had psychologists, psychiatrists, acupuncturists, and all of her time – and I had to be good, aware that it was my duty to be the stable pillar in our trembling home. There was no room for me to feel sad about my father’s death or stressed about our home life, to not excel at school or work, and it didn’t seem fair for me to have a problem of my own. So I kept my insomnia under wraps and continued to manage it myself, ingesting a variety of over-the-counter drugs. Once my body adjusted to Tylenol PM and it stopped knocking me out, I went shopping at CVS for new pills: NyQuil, Benadryl, and anything else that contained those magic words – “diphenhydramine citrate.”

The medicated people on television called out to me, their faces at peace in the dark. They greeted new days with smiles rather than caffeine pills and energy cocktails.

It wasn’t until 2006, once I’d graduated college at Fordham University, begun graduate school there in the evenings, and gotten a job as an editor for a technology publication, that I discovered the world of sleep prescriptions. On one of my nights spent awake, watching endless hours of Golden Girls reruns, I was intrigued by a 3 a.m. commercial for Ambien. The medicated people on television called out to me, their faces at peace in the dark. They greeted new days with smiles rather than caffeine pills and energy cocktails. I jotted down the medication’s name and felt ecstatic about the idea that I could be like those people too. Ambien would be my savior.

I called my doctor’s office the next day and told the secretary I wanted a prescription. She told me to come in. When I arrived, I gave my physician a brief account of my sufferings and told him about the commercial I’d seen. He didn’t need convincing – the script was filled out before I could finish my saga, and he handed it to me with a self-satisfied smile. I picked up the medication from the pharmacy later that day and popped the top off the orange bottle like a champagne cork, eager to celebrate this new milestone. That night, I placed the white circle on the tip of my tongue. It dissolved a little before I could swallow it down, leaving a bitter taste in my mouth. The pills I’d swallowed before were coated and didn’t have a flavor. This was the taste of transformation, I thought. I imagined the drug settling into my body and putting all of my anxious parts to rest. Getting into bed, I rolled to my side, closed my eyes, and smiled. Everything was about to change.

I enjoyed eight hours of slumber with the little white pill at first. I’d swallow one and be asleep within the half hour, knocked out. I woke up each day a little drowsy but rested nonetheless.

And then, after a month, the meds turned on me. One morning I awoke to find my laptop next to my bed. I opened the lid and discovered I’d spent the night posting semi-literate comments on the message board of my company’s publication. I'd composed long-winded comparisons between Google and my mother and shared them with our thirty thousand registered readers. I deleted the comments before my employers could see them and left for work, fearful about what else I could have done.

Soon I began waking in the morning after an hour or two of slumber to more clues indicating I had spent the night in a delirious state.

I hoped it was just a fluke and continued to take Ambien for the next couple of months. I discovered that by breaking the pill in half, or chewing it, it would hit me faster and I would fall asleep. That remedy only worked for so long, though, and soon I began waking in the morning after an hour or two of slumber to more clues indicating I had spent the night in a delirious state. I’d receive calls from people letting me know they’d heard from me the night before, like the time my friend told me I'd phoned her at midnight to describe the “Nicole and Tim heads” that were bouncing around my room. Tim was my boyfriend of three years, and after taking my medication one evening I saw the faces from our framed photographs floating in bubbles in the air, verbalizing the reservations I was having about our future together. “Look at their pictures, they seemed so happy,” they’d said.

When my cell phone call log didn’t reveal any nighttime antics, my laptop often beamed with events of the evening past. There were the Facebook messages I sent, informing friends I didn’t like the guys they were dating. I’d follow these up in the more-sober morning with a regretful, “But as long as you’re happy . . . !” There was the email exchange I didn’t remember having with a former acquaintance from St. Francis Prep in which I questioned his sexuality and reassured him that I could be there for him if he needed to come out.

I was mortified in the morning to find his reply: “Really, I’m straight. Thanks anyway. Are you OK?”

“I’m fine. Sorry about that,” I replied, hoping we’d never come in contact again.

Realizing Ambien was no longer working the way it should, I visited my physician to tell him about what was happening, to tell him it was time to try something different.

“What you’re describing is unusual. This is a great drug. Even my nieces take it!” he said. “Try again. Just make sure when you take it you get right in bed and close your eyes.” He increased my prescription to one and a half milligrams and sent me on my way.

Trusting my doctor, I tried his suggestion, but it wasn’t long before I was again spending the evening hours hallucinating rather than sleeping. Another next-day conversation with a friend revealed I had called her the night before in a panic that there was a male sheep in a housedress standing at the foot of my bed, his curved horns grazing up against the pitched attic ceiling.

A week later, groggy from the Ambien that remained in my system after a sleepless night, I left my house with a bowl full of cereal and milk, ready to drive myself to the train. With the breakfast sloshing around in my lap, I put the car in reverse, unsure how to operate the vehicle and spoon wet Cinnamon Toast Crunch into my mouth. At the edge of my driveway, I tried to work the steering wheel and breakfast bowl, paying little mind to my foot on the brake pedal, which slipped. My Honda Accord rolled out into the street, and the truck barreling down the road to came to a screeching halt just in time. Snapped alert and mouthing apologies, I picked up the dish from my lap, left it in the road, and continued on my drive to work.

My doctor had dismissed the idea that Ambien could be making me delirious, but a quick Web search later that day proved that my experience was not just common, but mild in comparison to what others were enduring. I found pages upon pages of forums about the drug in which people detailed going for drives, getting into accidents, and having no recollection of it the next day. They spoke of cooking meals under the influence of Ambien, or taking scalding showers. A couple of posters confessed to attempting suicide, not knowing about it until they awoke in the hospital and a family member recounted the horrifying details for them. I closed out of the forums and flushed my remaining pills down the toilet.

For the next several months I tried going back to my old ways of over-the-counter meds, but it was rare that they worked. I tried melatonin and another natural remedy from GNC called Alteril. These did the trick for a month or so, but soon ceased to help, leaving me restless and hopeless. I made an appointment with another doctor, wanting to get a referral to a sleep clinic. He scoffed at the idea and said they would only end up recommending pills. When I asked about trying hypnosis, he laughed and said it was a waste of time. Instead he wrote me a prescription for Ativan, an anti-anxiety drug, and sent me on my way.

For a while, Ativan helped to calm my nerves enough to allow me to fall asleep. I continued to take it for a few months, bouncing between rested and sleepless nights; slicing the pills in half or chewing them in hopes they’d be more effective. That spring I moved out of my childhood home and into an Upper East Side studio. I’d hoped the new environment and a queen-sized bed would somehow help me overcome the problem that had plagued me for as long as I could remember. I’d hoped I could leave my insomnia behind in that twin bed in the attic, that it wouldn’t follow me to another borough.

I was wrong. Despite the different location and the anti-anxiety medication, I spent most nights in my studio, struggling to hear silence above the voices of my worried neurons. I watched the numbers on my bedside clock creep toward new mornings, a bit maudlin that the gadget and I were sharing this transition to daytime together.

I began to think the only way out of this insomniac’s hell would be to die.

On bad nights I took a combination of meds – the anti-anxiety pill, a Benadryl – to knock myself out. On worse nights, I’d ingest this cocktail and stare at the wall until my alarm went off. I once spent a week without a minute’s sleep and began to think the only way out of this insomniac’s hell would be to die.

After seven days without rest, I confided in a friend that I didn’t know where to turn from here and I didn’t know why this was such a major problem for me.

“Have you ever tried thinking back to the first time you couldn’t sleep?” she said.

It seemed like a simple question, but I’d never considered it before. As soon as I did, the memory snapped right into vision, as though it were waiting to be summoned.

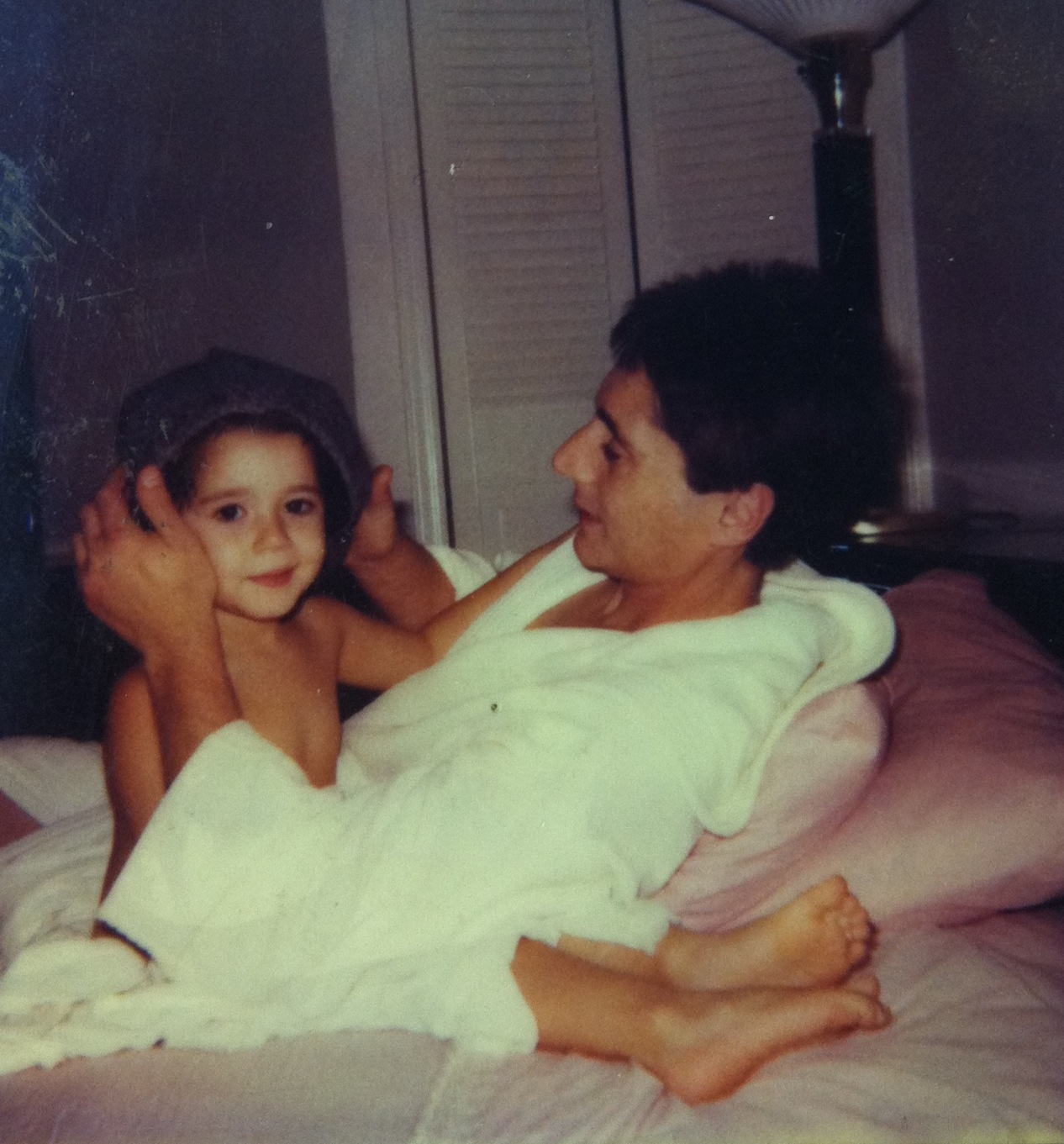

The day my father died, Mom told me to sleep in bed with her. I crawled in, occupying his vacant space with my six-year-old body. I snuggled my head against his pillow. It was flat – not much thicker than the pillowcase surrounding it. He liked it like that, so I did too. I slept in bed with Mom for the next four years. With our fingers interlocked, we breathed each other to sleep, silent lullabies. I thought if we stayed like that forever we could watch one another. But when I turned ten Mom said I was old enough to get my own room.

“Dad would want me to save his place,” I said, gripping her pink carpet with my bare toes to keep from crying.

Mom sighed. “He’d want you to have your own bed.”

My father had been gone for four years, but it was that night that I realized he wasn’t coming back. In my twin bed, I clutched the stuffed dog he'd bought me, my head on his pillow, my face turned toward his photo on the nightstand. I stayed like that all night, while reminders of his death stabbed my stomach.

Dad had died in the middle of a November night when I was asleep. Mom had made that okay for a while until it wasn’t. Sixteen years later, I didn’t want to believe I was still affected by his absence, but in my first studio apartment in Manhattan, I looked over at my bed, at that same stuffed dog my father had bought me twenty years ago, the only childhood memento I’d brought to my new home.

Recognizing my insomnia was rooted in this trauma, I was ready to reconsider hypnosis, hoping I could finally overcome it for good, rather than keep applying drugs as Band-Aids. I also became obsessed with the idea that hypnosis would uncover repressed memories, that while in my trance I would be faced with visions of my dad and somehow reconnect with him again.

With a bit of Googling, I found there was a hypnosis center twenty blocks south of my apartment. I emailed the office to request any forms I’d need to fill out prior to my visit and to ask for an appointment time. An administrator wrote me back providing paperwork and a day to come in. Without a hint of intended irony, the email also said I should arrive for my treatment well rested.

The following week I rode my bike down to the building on Sixty-third Street and First Avenue. I hadn’t slept much the night before and worried it would affect my ability to be treated. The more I told myself to focus on other thoughts, the more I fueled my anxiety. When I arrived, I discovered that the “hypnosis center” was an apartment building, and that the “hypnosis lab” was a living room with a recliner, a glowing, electronic rock, and a white noise machine from Bed, Bath & Beyond.

Handing the hypnotist, Jeff, three hundred and fifty dollars from my savings account, I asked him if we’d uncover the subconscious reasons behind my insomnia.

“I’d love to be able to articulate the root cause of this,” I said.

“That’s unlikely,” he said, putting my check in his drawer.

“Oh . . . it’s just that I think my insomnia is related to my dad’s death. He died when I was six, and I slept in bed with my mom for four years. I think the problem started when I moved to my own room.”

I expected Jeff to look impressed or curious to uncover more. Instead, he shrugged, and said, “The important part is getting you to be able to sleep, not dwelling on the past, right?”

I nodded, but my agreement felt insincere. With the prospect of sleep as the only outcome of this treatment, I was less excited.

Jeff directed me toward the recliner and told me to put my hands at my sides and my feet up. He switched on the white noise machine.

“Close your eyes.”

I did as he said and tried to silence my mind.

“Okay, Nicole. Make sure you’re taking deep breaths, in and out. I’m going to use my voice to walk you through a series of scenes. Try to picture them as best as you can and soon you’ll be in a trance-like state. Now imagine you’re walking through a forest, picture the trees, and the noises, keep walking, walking . . . .”

Jeff guided my mind through a forest, and eventually to a beach, where I was to picture the waves, and the birds flying overhead. I was trying to concentrate but I didn’t feel like I was being hypnotized. I felt I could open my eyes and get up and leave, unaffected. I tried to push those thoughts away and focus on the soothing words. Jeff interrupted his scene description to cough.

“Excuse me,” he said.

I was losing focus and wishing I’d kept my money.

“Okay, we’re going to count down from ten now, and with each number you should feel yourself getting deeper and deeper into a trance,” he said.

I focused on the numbers. Ten, I was still there, alert, panicking; nine, nothing changed; eight, seven, six, I was just as present. At the mention of five, though, I felt my right hand go numb, and at four, my left one. I wondered for the moment if I was sitting on them, if they had fallen asleep, but by the time we got to one, I was somewhere else. I still felt present but closer to the beach Jeff was describing. My own skeptical thoughts got quieter and soon disappeared as Jeff’s soft voice took over.

He told me it was time to release negative thoughts and watch them float away. To say good-bye to anxieties about life and death, to do away with the idea that I can’t sleep unless I take pills. He said to replace these with positive thoughts: I can sleep naturally. I am a happy person who deserves a restful life. I pictured the negative words entering a cyclone and disappearing. I watched the positive expressions Jeff was reciting emerge and remain in the air, present and available.

Jeff said the session was coming to an end and he would begin counting forward from one to ten to bring me back. When he reached the number five I felt my hands again. I wiggled my fingers. At the end of the countdown, he told me to open my eyes. I did and felt awkward, there in that room with this stranger, not having any idea what the outcome of this would be.

He gave me further instructions on how to fight insomnia on a regular basis: spend as much time as possible outdoors during the day; stop drinking caffeine after noon; take fish oil capsules; use an amber light or sit in darkness for an hour before going to sleep in order to allow my body to secrete natural melatonin. He suggested writing my own positive affirmations to repeat each morning and practicing yoga and breathing exercises.

That night I went home and waited for the magic to work.

That night I went home and waited for the magic to work. It didn’t. I stayed up all night thinking it failed, thinking I was ridiculous to even try it. In the middle of the night I resorted to the pills and curled my knees to my chest as I entertained my usual panicked thoughts.

I sent Jeff a frantic email in the morning and left him messages asking what I should do. He called back and said to stay calm, do all of the things he suggested, and avoid taking any pills. I agreed and spent the next several days obeying his every instruction. I went running in the mornings around the reservoir in Central Park in order to spend more time in the sunlight. I stopped drinking coffee after 11 a.m., for good measure. In the evenings, I turned off all lights except the amber bulb, which I kept on as I practiced slow breathing and meditation.

A couple of days later, I felt a calmness I’d never experienced before. I got into my bed, and with a mind full of quiet, I fell asleep unassisted for the first time since I was a child.

It has been over a year that I am able to sleep without taking pills, a feat I’d considered superhuman. I feel happier, well rested even when I stay up too late. I’ve stopped dreading the nighttime and started thinking of bed as a positive place. Hypnosis helped me overcome a mental certainty that, for me, natural rest was impossible.

But there are still those nights when I lie awake staring at walls wondering about the root of my insomnia, worrying that, by losing that part of me, I’m forfeiting my only remaining attachment to the father I didn’t get to know. I question if, with each restful night, I’m consenting to forget him. Some evenings these thoughts consume me, and with my old stuffed dog in the nook of my arm, I look toward the window and wait for dawn.

Nicole Ferraro is a writer and editor living in New York City. Her creative non-fiction essays have appeared in The New York Times, Our Town, New York Press, Mr. Beller's Neighborhood, and The Frisky. She is editor in chief of InternetEvolution.com and has performed in several storytelling shows, including The Story Collider.

Art by Lena H. Chandhok.